McKinsey Mind - Ethan M. Rasiel, Paul N. Friga

This blogpost is not an exhaustive summary of the book. Just contains the notes I took

-

MECE (Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive) in the context of problem solving means separating your problem into distinct, nonoverlapping issues while making sure that no issues relevant to your problem have been overlooked

- Importance of structured thinking:

- Without structure, your ideas won’t stand up.

- Use structure to strengthen your thinking.

-

The most common tool McKinsey-ites use to break problems apart is the logic tree, a hierarchical listing of all the components of a problem, starting at the “20,000-foot view” and moving progressively downward

-

Let’s suppose that Acme’s board has called your team in to help answer the basic question “How can we increase our profits?” The first question that might pop into your head upon hearing this is, “Where do your profits come from?” The board answers, “From our three core business units: widgets, grommets, and thrum-mats.” “Aha!” you think to yourself, “that is the first level of our logic tree for this problem.” You could then proceed down another level by breaking apart the income streams of each business unit, most basically into “Revenues” and “Expenses,” and then into progressively smaller components as you move further down the tree. By the time you’ve finished, you should have a detailed, MECE map of Acme Widgets’ business system

-

Finally, an initial hypothesis saves you time by forcing you and your team to focus only on those issues that can prove or disprove it. This is especially helpful for those who have trouble focusing and prioritizing

-

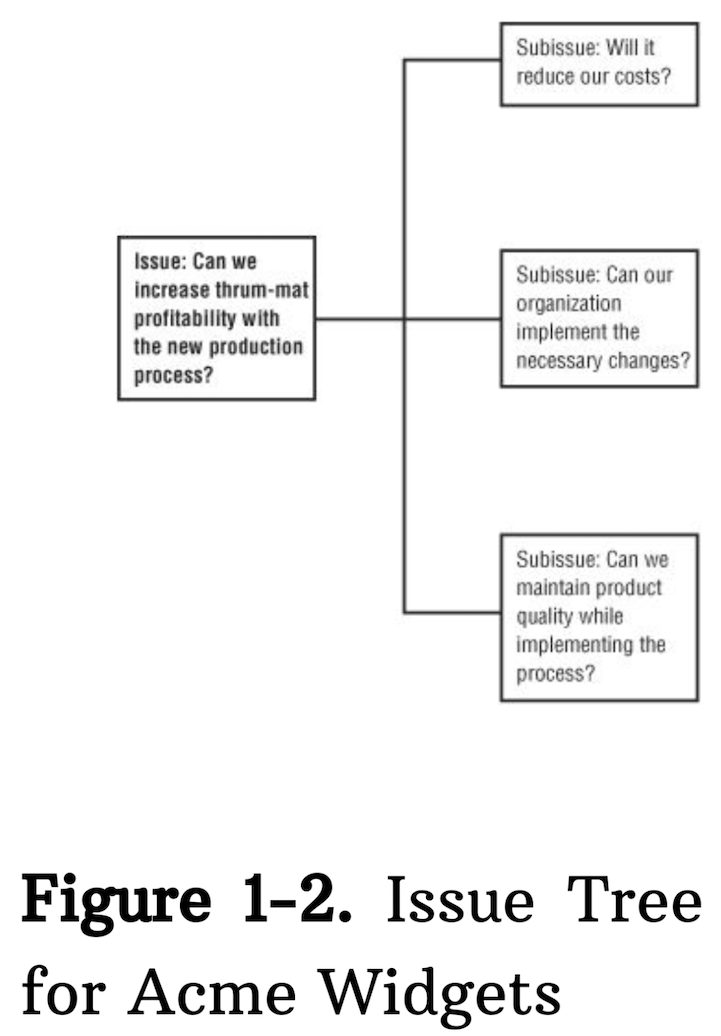

An issue tree is the evolved cousin of the logic tree. Where a logic tree is simply a hierarchical grouping of elements, an issue tree is the series of questions or issues that must be addressed to prove or disprove a hypothesis. Issue trees bridge the gap between structure and hypothesis. Every issue generated by a framework will likely be reducible to subissues, and these in turn may break down further. By creating an issue tree, you lay out the issues and subissues in a visual progression. This allows you to determine what questions to ask in order to form your hypothesis and serves as a road map for your analysis. It also allows you very rapidly to eliminate dead ends in your analysis, since the answer to any issue immediately eliminates all the branches falsified by that answer

-

What would an issue map look like for reducing the thrum-mat curing process for Acme industry? As you and your team discuss it, several questions arise: Will it actually save money? Does it require special skills? Do we have those skills in the organization? Will it reduce the quality of our thrum-mats? Can we implement the change in the first place?

-

When laying out your issue tree, you need to come up with a MECE grouping of these issues and the others that arise. As a first step, you need to figure out which are the top-line issues, the issues that have to be true for your hypothesis to be true. After a bit of brainstorming, you isolate three questions that address the validity of your hypothesis: Will shortening the curing process reduce our costs? Can we, as an organization, implement the necessary changes? If we implement this change, can we maintain product quality? Put these issues one level below your hypothesis

- The answer to each of these questions lies in several more questions. You will have to answer those in turn before you can come up with a final yes or no. As you take each question down one or more levels, your analysis road map will begin to take shape

-

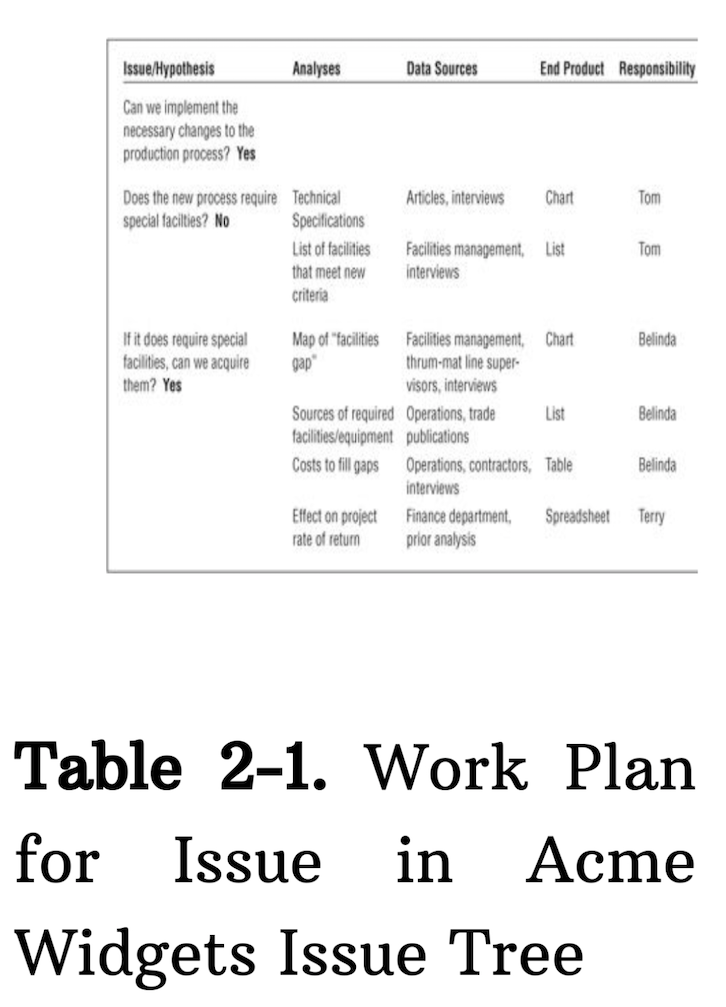

The issue “Can we implement the necessary changes?” throws off numerous subsidiary questions. Some of them came out in the initial brainstorming, while others will arise when you spend more time thinking specifically about the issue. Just as you did for the main issue, you need to figure out the logical progression of these questions. For the sake of this exercise, let’s say there are two top-line questions for this issue: (1) Does the new, shorter process require special facilities that we don’t have? (2) Does it require special skills that we don’t have? For both of these questions, the ideal answer, “no,” shuts down any further inquiry. If, however, the answer to either of these questions is yes, the hypothesis is not immediately invalidated. Rather, this answer raises additional questions that must be answered. For example, in the case of facilities, you would ask, “Can we build or buy them?” If the answers to these questions lower down the tree turn out to be no, then your hypothesis is indeed in jeopardy

-

Find the key drivers. The success of most businesses depends on a number of factors, but some are more important than others. When your time and resources are limited, you don’t have the luxury of being able to examine every single factor in detail. Instead, when planning your analyses, figure out which factors most affect the problem, and focus on those. Drill down to the core of the problem instead of picking apart each and every piece. Look at the big picture. When you are trying to solve a difficult, complex problem, you can easily lose sight of your goal amid the million and one demands on your time. When you’re feeling swamped by it all, take a metaphorical step back, and figure out what you’re trying to achieve. Ask yourself how the task you are doing now fits into the big picture. Is it moving your team toward its goal? If it isn’t, it’s a waste of time, and time is too precious to waste. Don’t boil the ocean. Work smarter, not harder. In today’s data-saturated world, it’s easy to analyze every aspect of a problem six ways to Sunday. But it’s a waste of time unless the analyses you’re doing add significant value to the problem-solving process. Figure out which analyses you need in order to prove (or disprove) your point. Do them, then move on. Chances are you don’t have the luxury to do more than just enough. Sometimes you have to let the solution come to you. Every set of rules has exceptions, and the McKinsey problem-solving process is no different in this regard. Sometimes, for whatever reason, you won’t be able to form an initial hypothesis. When that’s the case, you have to rely on your analysis of the facts available to point your way to an eventual solution

- Four lessons that will help you speed up your decision-making cycle:

- Let your hypothesis determine your analysis.

- Get your analytical priorities straight.

- Forget about absolute precision.

- Triangulate around the tough problems

- When designing your analysis, you have a specific end product in mind: your work plan. A comprehensive work plan begins with all the issues and subissues you identified during the framing of your initial hypothesis. For each issue or subissue, you should list the following elements:

- Your initial hypothesis as to the answer

- The analyses that must be done to prove or disprove that hypothesis, in order of priority

- The data necessary to perform the analysis

- The likely sources of the data (e.g., Census data, focus groups, interviews)

- A brief description of the likely end product of each analysis

- The person responsible for each end product (you or a member of your team)

- The due date for each end product

-

When it comes time to prove your initial hypothesis, efficient analysis design will help you hit the ground running. You and your team will know what you have to do, where to get the information to do it, and when to get it done. The work-planning process also serves as a useful reality check to the sometimes intellectualized pursuit of the initial hypothesis

-

In interviewing, McKinsey emphasizes preparation and courtesy. Be prepared: write an interview guide. An interview guide is simply a written list of the questions you want to ask, arranged in the order you expect to ask them.

-

A hypothesis, after all, must still be proved or disproved, and data on their own are mute. It is up to you and your team to use those facts to generate insights that will add value to your organization. All the multimegabyte spreadsheets and three-dimensional animated pie charts in the world don’t mean anything unless someone can figure out the actions implied by these analyses and their value to the organization

-

Don’t make the facts fit your solution. You and your team may have formulated a brilliant hypothesis, but when it comes time to prove or disprove it, be prepared for the facts and analyses to prove you wrong. If the facts don’t fit your hypothesis, then it is your hypothesis that must change, not the facts

-

When interpreting your analyses, you have two parallel goals: you want to be quick, and you want to be right

- How to do data interpretation: - Always ask, “What’s the so what?” - Perform sanity checks. - Remember that there are limits to analysis.

-

Always ask, “What’s the so what?” When you put together your analysis plan, you were supposed to eliminate any analyses, no matter how clever or interesting, that didn’t get you a step closer to proving or disproving your original hypothesis. No matter how good your work plan, however, it is almost inevitable that you will have to go through another filtering process once you’ve gathered the data, crunched the numbers, and interpreted the interviews. Some of your results will turn out to be dead ends: interesting facts, neat charts, but nothing that helps you get closer to a solution. It’s your job to weed out these irrelevancies.

-

Ask “What’s the so what?” for a particular analysis. What does it tell us, and how is that useful? What recommendation does it lead to?

-

A consultant must take the disparate messages of his analyses and synthesize them into insights that will solve his client’s problem. That happens best when every analysis meets the test of “So what?”

-

Perform sanity checks. Obviously, one wants to be as accurate as possible, but in a team situation you, as team leader, probably don’t have time to perform a detailed check on every analysis your team produces. Whenever someone presents you with a new recommendation or insight, however, you can do a quick sanity check to ensure that the answer at least sounds plausible

-

A sanity check lets you swiftly ascertain whether a particular analysis is at least within the bounds of probability. A sanity check consists of a few pointed questions, the answers to which will show whether a recommendation is feasible and whether it will have a noticeable impact on the organization

-

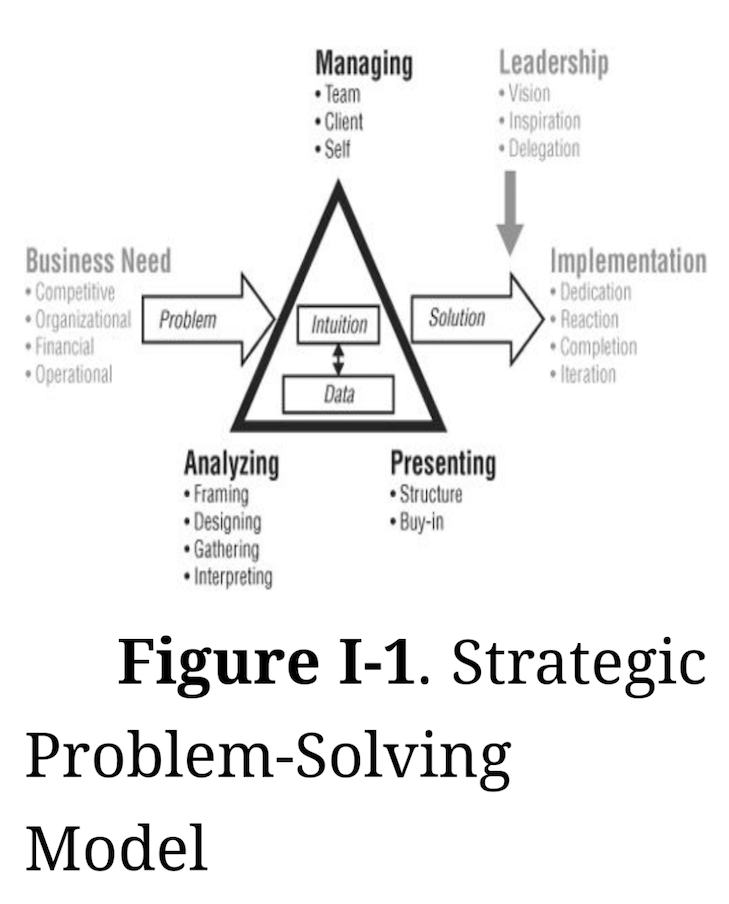

Remember that there are limits to analysis. Analysis plays a vital role in the McKinsey problem-solving process, but when all is said and done, it can take you only so far. You have to draw inferences from the analyses; they won’t speak for themselves. You’ve reached the point in our consulting model where intuition takes the lead from data

-

Data without intuition are merely raw information, and intuition without data is just guesswork. Put the two together, however, and you have the basis for sound decision making

-

Make sure the solution fits your client. Management, like politics, is the art of the possible. The most brilliant solution, backed up by libraries of data and promising billions in extra profits, is useless if your client or business can’t implement it. Know your client. Know the business’s strengths, weaknesses, and capabilities—what management can and cannot do. Tailor your solutions with these factors in mind

- Depending on your position and power within your organization and on your corporate culture, you may have to rely on someone else’s conception of the CEO focus (perhaps, even, your CEO’s). Nevertheless, the CEO focus should be your touchstone as you put together your recommendation. As your next step, ask how your decisions will add value to your client or organization. For each action that you recommend, how large will the payoff be? Is it large enough to justify the required commitment of time, energy, and resources? How does it compare to the other recommendations you make? If it is significantly smaller in terms of potential result, other, larger projects should come first. As chair of retail banking at Key Corp., Jim Bennett had to make decisions like this every day:

-

For me, the metric has to be, “Is this really going to make a difference?” At Key, as in most companies, decisions are typically input-oriented rather than performance- and output-oriented. We tried to change that paradigm by going public with performance commitments—”We’re going to grow our earnings by X “—which put us on the hook to come up with projects that would meet that goal. This focus on funda mental and lasting differences in performance forces us to take an aggressive 80/20 view of any potential project. We have to ask, “If we commit these resources for something approaching this predicted return, what difference is it going to make to hitting our performance objective?”. For example, my staff brought me a data warehouse project which required an investment of $8 million for a wonderful internal rate of return and payback in two or three years. I said, “Look, guys, if we can’t get at least 10 times the impact for this expenditure, I’m not taking this to the board, so go back and find some way that we’re going to generate a return of at least 10 times whatever it is we spend.” Everything is judged on its ability to help us meet our performance challenge.

-

A successful presentation bridges the gap between you—the presenter—and your audience. It lets them know what you know. You can make this process easy for your audience by giving your presentations a clear and logical structure. Fortunately, if you have been adhering to the principles of this book, then you already have a solid basis for such a structure: your initial hypothesis. If you broke out your initial hypothesis into a MECE set of issues and subissues (and suitably modified them according to the results of your analysis), then you have a ready-made outline for your presentation. If you have a well-structured, MECE hypothesis, then you will have a well-structured, MECE presentation. Conversely, if you can’t get your presentation to make sense, then you may want to rethink the logic of your hypothesis.

-

If you proved your initial hypothesis say so in your first slide. With that slide, you’ve established the structure of your presentation for your audience: they know where you’re going and will have an easy time following you. The rest of your presentation flows out of the first slide. Each of those major points under your initial hypothesis constitutes a section of your presentation. Each section will consist of the various levels of subissues under each of those major issues

-

You may have found one aspect of this structure unusual. We recommend starting with your conclusion. Many presentations take the opposite approach, going through all the data before finally springing the conclusion on the audience. While there are circumstances where this is warranted—you may really want to keep your listeners in suspense—it is very easy to lose your audience before you get to your conclusions, especially in data-intensive presentations. By starting with your conclusion, you prevent your audience from asking, “Where is she going with this?”

-

Having your conclusions or recommendations up front is sometimes known as inductive reasoning. Simply put, inductive reasoning takes the form, “We believe X because of reasons A, B, and C.” This contrasts with deductive reasoning, which can run along the lines of, “A is true, B is true, and C is true; therefore, we believe X.” Even in this simplest and most abstract example, it is obvious that inductive reasoning gets to the point a lot more quickly, takes less time to read, and packs a lot more punch. McKinsey prefers inductive reasoning in its communications for precisely these reasons

-

Prewiring means taking your audience through your findings before you give your presentation. Tailoring means adapting your presentation to your audience, both before you give it and, if necessary, on the fly. Together, these techniques will boost your chances of making change happen in your organization

-

Prewire everything. A good business presentation should contain no shocking revelations for the audience. Walk the relevant decision makers in your organization through your findings before you gather them together for a dog and pony show. McKinsey-ites have a shorthand expression for sending out your recommendations to request comment from key decision makers before a pre sentation: prewiring. At McKinsey, consultants learn to prewire every presentation.

-

In business, people don’t like surprises. By surprises, we don’t mean getting an extra day off or a bigger than expected bonus; we mean new information that forces decision makers to change their plans or alter their procedures. That’s why risky investments like small stocks have higher expected returns than safe investments like government bonds. Prewiring reduces your potential for surprises. It also acts as a check on your solutions because those who review your recommendations may mention something that you missed in your research and just might change your results.

-

More importantly, discussing your results outside the context of a large meeting increases your chances of getting those decision makers to buy into your ideas. In the intimacy of a one-on-one meeting, you open up your thought process to them in a way that is difficult to do in more formal settings. You can find out their concerns and address them. If someone takes issue with a particular recommendation, you may be able to work out a compromise before the big meeting, thereby ensuring that she will be on your side when the time comes

-

The earlier you can start the prewiring process, the better. By identifying and getting input from the relevant players early on, you allow them to put their own mark on your solution, which will make them more comfortable with it and give them a stake in the outcome. You also give those outside your team a chance to expose any errors you may have made or opportunities you may have missed, and you still have time to correct them.

-

When it comes to tailoring, however, sometimes you have to act on the fly. A good presentation structure will give you the flexibility to change your pitch depending on the audience’s reaction. You should never be so locked in to your script that you can’t deviate from it if the occasion demands

-

Keep the information flowing. Information is power. Unlike other resources, information can actually increase in value as it is shared, to the benefit of everyone on your team. For your team to succeed, you have to keep the information flowing. You don’t want someone to make a bad decision or say the wrong thing to a client just because he’s out of the loop. Teams communicate mainly through messages and meetings. Both should be kept brief and focused. In addition, remember the unscientific but powerful art of learning by walking around—random meetings to connect with team members outside of scheduled meetings

- Create a pull rather than a push demand. Bill Ross left McKinsey as an engagement manager. When he moved to GE, even though he didn’t have outside clients, he realized that he had to start selling:

-

My client is really the CEO of this business. I have more clients as well—the managers of specific business units. We have to sell. The products I’m selling are my ideas. In many cases, I’m trying to get them to think differently and put my thoughts into their thoughts—to get them engaged with my ideas, so that when they have a problem, they turn to me. This requires an up-front investment of resources and time. That’s the secret—to create awareness of your offering so that selling becomes less of a push and more of a pull. This is the practical application of the McKinsey approach to indirect selling. Rather than sticking a foot in the door and barging in cold, build up a reputation and let it preceed you. Put the client in a position to recognize that you’re the one who can fill her need— then she’ll call you.

-

Effective selling, becomes the identification of client needs and the building of expertise around them. Once you’ve done that, you can begin the subtle art of indirect selling by making people aware of what you know. Since you have done your research up front, you don’t need to be explicit in your sales effort. Just allow the potential client to make the connection between his need and your expertise

-

Share and then transfer responsibility. At some point, you have to learn to let go. When it comes to client involvement, one of the common arguments holding back such efforts is a concern over quality or efficiency. The problem with this orientation is that it focuses too much on the short term. The first step is to take the risk of some inefficiency in order to involve the client in a greater role

-

Clients (internal or external) who were involved in the problem-solving process make the best advocates. This method also ensures that an eventual transfer takes place, which was facilitated by the sharing of the overall process throughout

-

Find your own mentor. Take advantage of others’experience by finding someone senior in your organization to be your mentor. Even though some firms have formal mentoring programs, you would still do well to take the initiative to find someone to steer you through the twists and turns of corporate life.

-

Hit singles. This isn’t a call to commit battery on the unwed, it’s a metaphor from baseball. You can’t do everything, so don’t try. Just do what you’re supposed to do, and get it right. It’s impossible to do everything yourself all the time. If you do manage that feat once, you raise unrealistic expectations from those around you. Then, when you fail to meet those expectations, you’ll have difficulty regaining your credibility. Getting on base consistently is much better than trying to hit a home run and striking out nine times out of ten.

-

Make your boss look good. If you make your boss look good, your boss will make you look good. You do that by doing your job to the best of your ability and letting your boss know everything you know when she needs to know it. Make sure she knows where you are, what you are doing, and what problems you may be having. However, don’t overload her with information. In return for your efforts, she should praise your contributions to the organization.

-

An aggressive strategy for managing hierarchy. Sometimes, to get things done, you have to assert yourself. If you face a vacuum in power or responsibility, fill it before someone else does. This strategy can be risky; the more so, the more hierarchical your organization. Be sensitive to the limits of others’ authority, and be ready to retreat quickly if necessary.

-

A good assistant is a lifeline. Having someone to perform the myriad support tasks required by a busy executive— typing, duplicating, messaging, and filing, to name but a few— can be exceptionally valuable. Whether the people who perform these tasks are called secretaries, assistants, interns, or simply junior staff, treat them well. Be clear about your wants and needs, and give them opportunities to grow in their responsibilities and careers, even if they are not on the executive track

-

Delegate around your limitations. Understanding the limitations of others: your client, your organization, your team, and even your organization’s structure is key. Now we recommend that you turn that same understanding inward and understand your own limitations. Know them for what they are and respect them. In a modern organization, you can’t last very long as a one-man band. Not even Tiger Woods plays in every golf tournament.

- Once you’ve recognized your limitations, you can go about circumventing them. Sometimes this just means having an assistant you can trust to handle your travel arrangements and messaging