Competing Against Luck - Clayton M. Christensen, Taddy Hall, Karen Dillon, David Duncan

Note: While reading a book whenever I come across something interesting, I highlight it on my Kindle. Later I turn those highlights into a blogpost. It is not a complete summary of the book. These are my notes which I intend to go back to later. Let’s start!

-

For most companies, innovation is still painfully hit or miss. And worst of all, all this activity gives the illusion of progress, without actually causing it. Companies are spending exponentially more to achieve only modest incremental innovations while completely missing the mark on the breakthrough innovations critical to long-term, sustainable growth. As Yogi Berra famously observed: “We’re lost, but we’re making good time!”

-

What’s gone so wrong? Here is the fundamental problem: the masses and masses of data that companies accumulate are not organized in a way that enables them to reliably predict which ideas will succeed. Instead the data is along the lines of “this customer looks like that one,” “this product has similar performance attributes as that one,” and “these people behaved the same way in the past,” or “68 percent of customers say they prefer version A over version B.” None of that data, however, actually tells you why customers make the choices that they do.

-

Let me illustrate. Here I am, Clayton Christensen. I’m sixty-four years old. I’m six feet eight inches tall. My shoe size is sixteen. My wife and I have sent all our children off to college. I live in a suburb of Boston and drive a Honda minivan to work. I have a lot of other characteristics and attributes. But these characteristics have not yet caused me to go out and buy the New York Times today. There might be a correlation between some of these characteristics and the propensity of customers to purchase the Times. But those attributes don’t cause me to buy that paper—or any other product.

-

If a company doesn’t understand why I might choose to “hire” its product in certain circumstances—and why I might choose something else in others—its data about me or people like me is unlikely to help it create any new innovations for me. It’s seductive to believe that we can see important patterns and cross-references in our data sets, but that doesn’t mean one thing actually caused the other. As Nate Silver, author of The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail—But Some Don’t, points out, “ice cream sales and forest fires are correlated because both occur more often in the summer heat. But there is no causation; you don’t light a patch of the Montana brush on fire when you buy a pint of Häagen-Dazs.”

-

Correlation does not reveal the one thing that matters most in innovation—the causality behind why I might purchase a particular solution. Yet few innovators frame their primary challenge around the discovery of a cause. Instead, they focus on how they can make their products better, more profitable, or differentiated from the competition.

-

When we buy a product, we essentially “hire” something to get a job done. If it does the job well, when we are confronted with the same job, we hire that same product again. And if the product does a crummy job, we “fire” it and look around for something else we might hire to solve the problem. Those customers weren’t simply buying a product, they were hiring the milk shake to perform a specific job in their lives. What causes us to buy products and services is the stuff that happens to us all day, every day. We all have jobs we need to do that arise in our day-to-day lives and when we do, we hire products or services to get these jobs done. Armed with that perspective, the team found itself standing in a restaurant for eighteen hours one day, watching people: What time did people buy these milk shakes? What were they wearing? Were they alone? Did they buy other food with it? Did they drink it in the restaurant or drive off with it?

-

It turned out that a surprising number of milk shakes were sold before 9:00 a.m. to people who came into the fast-food restaurant alone. It was almost always the only thing they bought. They didn’t stop to drink it there; they got into their cars and drove off with it. So we asked them: “Excuse me, please, but I have to sort out this puzzle. What job were you trying to do for yourself that caused you to come here and hire that milk shake?” At first the customers themselves had a hard time answering that question until we probed on what else they sometimes hired instead of a milk shake. But it soon became clear that the early-morning customers all had the same job to do: they had a long and boring ride to work. They needed something to keep the commute interesting. They weren’t really hungry yet, but they knew that in a couple of hours, they’d face a midmorning stomach rumbling. It turned out that there were a lot of competitors for this job, but none of them did the job perfectly. “I hire bananas sometimes. But take my word for it: don’t do bananas. They are gone too quickly—and you’ll be hungry again by midmorning,” one told us. Doughnuts were too crumbly and left the customers’ fingers sticky, making a mess on their clothes and the steering wheel as they tried to eat and drive. Bagels were often dry and tasteless—forcing people to drive their cars with their knees while they spread cream cheese and jam on the bagels. Another commuter confessed, “One time I hired a Snickers bar. But I felt so guilty about eating candy for breakfast that I never did it again.” But a milk shake? It was the best of the lot. It took a long time to finish a thick milk shake with that thin straw. And it was substantial enough to ward off the looming midmorning hunger attack. One commuter effused, “This milk shake. It is so thick! It easily takes me twenty minutes to suck it up through that thin straw. Who cares what the ingredients are—I don’t. All I know is that I’m full all morning. And it fits right here in my cup holder”—as he held up his empty hand. It turns out that the milk shake does the job better than any of the competitors—which, in the customers’ minds, are not just milk shakes from other chains but bananas, bagels, doughnuts, breakfast bars, smoothies, coffee, and so on. As the team put all these answers together and looked at the diverse profiles of these people, another thing became clear: what these milk shake buyers had in common had nothing to do with their individual demographics. Rather, they all shared a common job they needed to get done in the morning.

-

“Help me stay awake and occupied while I make my morning commute more fun.” The morning job needs a more viscous milk shake, which takes a long time to suck up during the long, boring commute. You might add in chunks of fruit, but not to make it healthy. That’s not the reason it’s being hired. Instead, fruit or even bits of chocolate would offer a little “surprise” in each sip of the straw and help keep the commute interesting. You could also think about moving the dispensing machine from behind the counter to the front of the counter and providing a swipe card, so morning commuters could dash in, fill a milk shake cup themselves, and rush out again. In the afternoon, I’m the same person, but in very different circumstances. The afternoon, placate-your-children-and-feel-like-a-good-dad job is very different. Maybe the afternoon milk shake should come in half sizes so it can be finished more quickly and not induce so much guilt in Dad. If this fast-food company had only focused on how to make its product “better” in a general way—thicker, sweeter, bigger—it would have been focusing on the wrong unit of analysis. You have to understand the job the customer is trying to do in a specific circumstance. If the company simply tried to average all the responses of the dads and the commuters, it would come up with a one-size-fits-none product that doesn’t do either of the jobs well.

-

People hired milk shakes for two very different jobs during the day, in two very different circumstances. Each job has a very different set of competitors—in the morning it was bagels and protein bars and bottles of fresh juice, for example; in the afternoon, milk shakes are competing with a stop at the toy store or rushing home early to shoot a few hoops—and therefore was being evaluated as the best solution according to very different criteria. This implies there is likely not just one solution for the fast-food chain seeking to sell more milk shakes. There are two. A one-size-fits-all solution would work for neither.

-

Shifting our understanding from educated guesses and correlation to an underlying causal mechanism is profound. Truly uncovering a causal mechanism changes everything about the way we solve problems—and, perhaps more important, prevents them. Take, for example, a more modern arena: automobile manufacturing.

-

Theory has a voice, but no agenda. A theory doesn’t change its mind: it doesn’t apply to some companies or people and not to others. Theories are not right or wrong. They provide accurate predictions, given the circumstances you are in.

-

Customers don’t buy products or services; they pull them into their lives to make progress. We call this progress the “job” they are trying to get done, and in our metaphor we say that customers “hire” products or services to solve these jobs.

-

We define a “job” as the progress that a person is trying to make in a particular circumstance. This definition of a job is not simply a new way of categorizing customers or their problems. It’s key to understanding why they make the choices they make. The choice of the word “progress” is deliberate. It represents movement toward a goal or aspiration. A job is always a process to make progress, it’s rarely a discrete event. A job is not necessarily just a “problem” that arises, though one form the progress can take is the resolution of a specific problem and the struggle it entails. Second, the idea of a “circumstance” is intrinsic to the definition of a job. A job can only be defined—and a successful solution created—relative to the specific context in which it arises. There are dozens of questions that could be important to answer in defining the circumstance of a job. “Where are you?” “When is it?” “Who are you with?” “While doing what?” “What were you doing half an hour ago?” “What will you be doing next?” “What social or cultural or political pressures exert influence?” And so on. Our notion of a circumstance can extend to other contextual factors as well, such as life-stage (“just out of college?” “stuck in a midlife crisis?” “nearing retirement?”), family status (“married, single, divorced?” “newborn baby, young children at home, adult parents to take care of?”), or financial status (“underwater in debt?” “ultra-high net worth?”) just to name a few. The circumstance is fundamental to defining the job (and finding a solution for it), because the nature of the progress desired will always be strongly influenced by the circumstance.

- The emphasis on the circumstance is not hair-splitting or simple semantics—it is fundamental to the Job to Be Done. In our experience, managers usually don’t take this into account. Rather they typically follow one of four primary organizing principles in their innovation quest—or

some composite thereof:

- Product attributes

- Customer characteristics

- Trends

- Competitive response

-

The point isn’t that any of these categories are bad or wrong—and they’re just a sampling of the most common. But they are insufficient, and therefore not predictive of customer behaviors.

-

Functional, Social, and Emotional Complexity: Finally, a job has an inherent complexity to it: it not only has functional dimensions, but it has social and emotional dimensions, too. In many innovations, the focus is often entirely on the functional or practical need. But in reality, consumers’ social and emotional needs can far outweigh any functional desires. Think of how you would hire childcare. Yes, the functional dimensions of that job are important—will the solution safely take care of your children in a location and manner that works well in your life—but the social and emotional dimensions probably weigh more heavily on your choice. “Who will I trust with my children?”

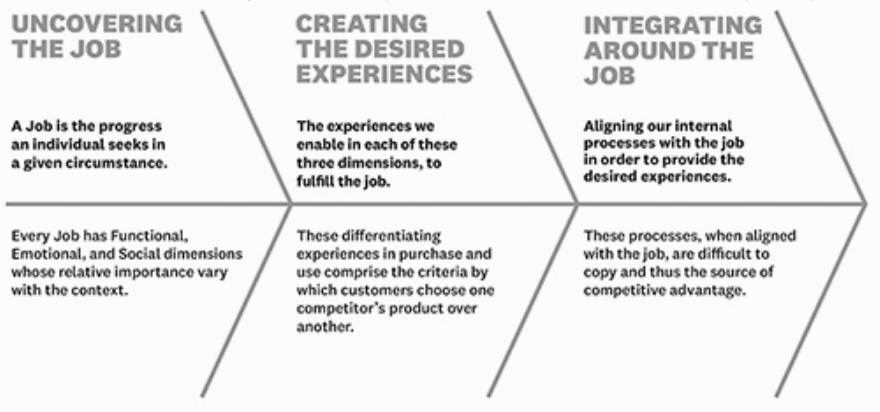

- What Is a Job? To summarize, the key features of our definition are:

- A job is the progress that an individual seeks in a given circumstance.

- Successful innovations enable a customer’s desired progress, resolve struggles, and fulfill unmet aspirations. They perform jobs that formerly had only inadequate or nonexistent solutions.

- Jobs are never simply about the functional—they have important social and emotional dimensions, which can be even more powerful than functional ones.

- Because jobs occur in the flow of daily life, the circumstance is central to their definition and becomes the essential unit of innovation work—not customer characteristics, product attributes, new technology, or trends.

- Jobs to Be Done are ongoing and recurring. They’re seldom discrete “events.”

- A well-defined job offers a kind of innovation blueprint. This is very different from the traditional marketing concept of “needs” because it entails a much higher degree of specificity about what you’re solving for. Needs are ever present and that makes them necessarily more generic. “I need to eat” is a statement that is almost always true. “I need to feel healthy.” “I need to save for retirement.” Those needs are important to consumers, but their generality provides only the vaguest of direction to innovators as to how to satisfy them. Needs are analogous to trends—directionally useful, but totally insufficient for defining exactly what will cause a customer to choose one product or service over another. Simply needing to eat isn’t going to cause me to pick one solution over another—or even pull any solution into my life at all. I might skip a meal. And needs, by themselves, don’t explain all behavior: I might eat when I’m not hungry at all for a myriad of reasons.

-

Jobs take into account a far more complex picture. The circumstances in which I need to eat, and the other set of needs that might be critical to me at that moment, can vary wildly. Think back to our milk shake example. I may opt to hire a milk shake to resolve a job that arises in my own life. What will cause me to choose the milk shake are the bundle of needs that are in play in those particular circumstances. That bundle includes not only needs that are purely functional or practical (“I’m hungry and I need something for breakfast”), but also social and emotional (“I’m alone on a long, boring commute and want to entertain myself, but I’d be embarrassed if one of my colleagues caught me with a milk shake in my hand so early in the morning”). In those circumstances, some of my needs have a higher priority than others. I might, for example, opt to swing into the drive-through (where I won’t be seen) of the fast-food chain for a milk shake for that morning commute. But under different circumstances—I have my son with me, it’s dinnertime, and I want to feel like a good dad—the relative importance of each of my needs may cause me to hire the milk shake for an entirely different set of reasons. Or to turn to another solution to my job altogether.

-

Many wonderful inventions have been, unwittingly, built only around satisfying a very general “need.” Take, for example, the Segway, a two-wheeled, self-balancing electric vehicle invented by Dean Kamen. In spite of the media frenzy around the release of Kamen’s “top secret” invention that was supposed to change transportation forever, the Segway was, by most measures, a flop. It had been conceived around the need of more efficient personal transportation. But whose need? When? Why? In what circumstances? What else matters in the moment when somebody might be trying to get someplace more efficiently? The Segway was a cool invention, but it didn’t solve a Job to Be Done that a lot of people shared. I see them from time to time in tourist spots around Boston or in our local mall, but especially compared with the prelaunch hype, very few people felt compelled to pull the Segway into their lives.

-

On the other end of the spectrum from needs are what I’ll call the guiding principles of my life—overarching themes in my life that are ever present, just as needs are. I want to be a good husband, I want to be a valued member of my church, I want to inspire my students, and so on. These are critically important guiding principles to the choices I make in my life, but they’re not my Jobs to Be Done. Helping me feel like a good dad is not a Job to Be Done. It’s important to me, but it’s not going to trigger me to pull one product over another into my life. The concept is too abstract. A company couldn’t create a product or service to help me feel like a good dad without knowing the particular circumstances in which I’m trying to achieve that. The jobs I am hiring for are those that help me overcome the obstacles that get in the way of making progress toward the themes of my life—in specific circumstances. The full set of Jobs to Be Done as I go through life may roll up, collectively, into the major themes of my life, but they’re not the same thing.

-

Jobs insights are fragile—they’re more like stories than statistics. When we deconstruct coherent customer episodes into binary bits, such as “male/female,” “large company/small company,” “new customer/existing customer,” we destroy meaning in the process. Jobs Theory doesn’t care whether a customer is between the ages of forty and forty-five and what flavor choice they made that day. Jobs Theory is not primarily focused on “who” did something, or “what” they did—but on “why.” Understanding jobs is about clustering insights into a coherent picture, rather than segmenting down to finer and finer slices.

-

To really grasp a job is to imagine you are filming a minidocumentary of a person struggling to make progress in a specific circumstance.

- Your Video Should Capture Essential Elements:

- What progress is that person trying to achieve? What are the functional, social, and emotional dimensions of the desired progress? For example, a job that occurs in a lot of people’s lives: “I want to have a smile that will make a great first impression in my work and personal life”; or a struggle many managers might relate to: “I want the sales force I manage to be better equipped to succeed in their job so that the churn in staff goes down.”

- What are the circumstances of the struggle? Who, when, where, while doing what? “I see a dentist twice a year and do all the right things to keep my teeth clean, but they never look white enough to me” or “It seems like every week, another one of my guys is giving notice because he’s burned out and I’m spending half my time recruiting and training new people.”

- What obstacles are getting in the way of the person making that progress? For example, “I’ve tried a couple of whitening toothpastes and they don’t really work—they’re just a rip-off” or “I’ve tried everything I can think of to motivate my sales staff: bonus programs for them, offsite bonding days, I’ve bought them a variety of training tools. And they still can’t tell me what’s going wrong.”

- Are consumers making do with imperfect solutions through some kind of compensating behavior? Are they buying and using a product that imperfectly performs the job? Are they cobbling together a workaround solution involving multiple products? Are they doing nothing to solve their dilemma at all? For example, “I’ve bought one of those expensive home whitening kits, but you have to wear this awful mouth guard overnight and it kind of burns my teeth . . .” or “I have to spend time making sales calls myself—and I don’t have time for that!”

- How would they define what “quality” means for a better solution, and what tradeoffs are they willing to make? For example, “I want the whitening performance of a professional dental treatment, without the cost and inconvenience” or “There are tons of ‘products’ and services I can purchase. But none of them actually help me do the job.”

-

It’s important to note that we don’t “create” jobs, we discover them. Jobs themselves are enduring and persistent, but the way we solve them can change dramatically over time. Think, for example, of the job of sharing information across long distances. That underlying job has not changed, but our solutions for it have: from Pony Express to telegraph to air mail to email and so on. For example, teenagers have had the job of communicating with each other without the nosy intervention of parents for centuries. Years ago, they passed notes in the school hallway or pulled the telephone cord all the way into the furthest corner of their room. But in recent years, teens have started hiring Snapchat, a smartphone app that allows messages to be delivered and then disappear almost instantly and a whole host of other things that could not even have been imagined a few decades ago. The creators of Snapchat understood the job well enough to create a superior solution. But that doesn’t mean Snapchat isn’t vulnerable to other competitors coming along with a better understanding of the complex set of social, emotional, and functional needs of teenagers in particular circumstances. Our understanding of the Job to Be Done can always get better. Adopting new technologies can improve the way we solve Jobs to Be Done. But what’s important is that you focus on understanding the underlying job, not falling in love with your solution for it

-

When a smoker takes a cigarette break, on one level he’s simply seeking the nicotine his body craves. That’s the functional dimension. But that’s not all that’s going on. He’s hiring cigarettes for the emotional benefit of calming him down, relaxing him. And if he works in a typical office building, he’s forced to go outside to a designated smoking area. But that choice is social, too—he can take a break from work and hang around with his buddies. From this perspective, people hire Facebook for many of the same reasons. They log onto Facebook during the middle of the workday to take a break from work, relax for a few minutes while thinking about other things, and convene around a virtual water cooler with far-flung friends. In some ways, Facebook is actually competing with cigarettes to be hired for the same Job to Be Done. Which the smoker chooses will depend on the circumstances of his struggle in that particular moment.

-

Managers and industry analysts like to keep their framing of competition simple—put like companies, industries, and products in the same buckets. Coke versus Pepsi. Sony PlayStation versus Xbox. Butter versus margarine. This conventional view of the competitive landscape puts tight constraints around what innovation is relevant and possible, as it emphasizes benchmarking and keeping up with the Joneses. Through this lens, opportunities to grab market share can seem finite, with most companies settling for gaining a few percentage points, within a zero-sum game.

-

But from a Jobs Theory perspective, the competition is seldom limited to products that the market chooses to lump into the same category. Netflix CEO Reed Hastings made this clear when recently asked by legendary venture capitalist John Doerr if Netflix was competing with Amazon. “Really we compete with everything you do to relax,” he told Doerr. “We compete with video games. We compete with drinking a bottle of wine. That’s a particularly tough one! We compete with other video networks. Playing board games.”

-

The competitive landscape shifts to something new, maybe uncomfortably new, but one with fresh potential when you see competition through a Jobs to Be Done lens.

- SNHU case study

- What are the experiences customers seek in order to make progress? There were no more leisurely responses to inquiries about financial aid. That twenty-four-hours-later generic email was transformed into a follow-up phone call from someone at SNHU in under ten minutes of an inquiry. In the competitive online-learning world, the first online-learning institution to actually speak to a prospective student is most likely the one to close the sale. So instead of being a perfunctory follow-up, the phone call itself, LeBlanc says, was seen as a crucial opportunity to remove barriers for the prospective student. “You can uncover and surface a lot of anxiety issues,” he says, “so those calls are with a well-trained counselor with all the information he needs at his fingertips [to help the student overcome whatever obstacles they’re facing]. Calls can go on for an hour, an hour and a half. At the end of the call, you’re engaged with us. And we know you’re much more likely to enroll.”

- What obstacles must be removed? Decisions about a prospect’s financial aid package and how much previous college courses would be counted toward an SNHU degree were resolved within days—instead of weeks or even months.

- What are the social, emotional, and functional dimensions? The university’s ads for the online program were completely reoriented so that they focused on how it could fulfill the job for later-life learners. The ads were aimed to resonate not just with the functional dimensions of the job, such as getting the training needed to advance in a career, but also with the emotional and social dimensions as well, such as the pride one feels in realizing a goal or the fulfillment of a commitment to a loved one. One ad featured a large SNHU bus roaming the country handing out large, traditionally framed diplomas to online learners who couldn’t be on campus for graduation. “Who did you get this degree for?” the voice-over asks, as the commercial captures glowing graduates in their home environment. “I got it for me,” one woman says, hugging her diploma. “I did this for my mom,” beams a thirty-something man. “I did it for you, bud,” one father says, holding back tears, as his young son chirps, “Congratulations, Daddy!”

- But perhaps most important, SNHU realized that enrolling prospects in a first class was only the beginning of doing the job or them. To truly fulfill the job that those applicants were hiring continuing education to do for them, SNHU had to make sure it succeeded in meeting their own goals. SNHU sets up each new online student with a personal adviser, who stays in constant contact—and notices red flags even before the students might—in order to help them continue to make the progress they want to make. Haven’t checked out this week’s assignment by Wednesday or Thursday? Your adviser will check in with you. The unit test went badly? You can count on a call from your adviser to see not only what’s going on with the class, but also what’s going on in your life. Your laptop is causing you problems? An adviser might just send you a new one.

- SNHU’s staggering growth suggests that LeBlanc and his colleagues deeply understand these students’ Jobs to Be Done. There are now twelve hundred College of Online and Continuing Education (COCE) staffers at that site in the former mill yard in Manchester, and more than seventy-five thousand students in thirty-six states and countries around the world. “There have been times when we almost broke the machine, we were outgrowing our systems so much,” LeBlanc recalls. When growth has been that rapid, SNHU has dialed back its recruiting efforts until it can reinforce its internal support and systems. LeBlanc knows that if SNHU fails to deliver on the job, students will not hesitate to fire it and seek something that does the job better

-

Your organization has to build the right set of experiences in how customers find, purchase, and use your product or service—and integrate all the corresponding processes to ensure that those experiences are consistently delivered. When you are solving a customer’s job, your products essentially become services. What matters is not the bundle of product attributes you rope together, but the experiences you enable to help your customers make the progress they want to make.

-

Organizations that lack clarity on what the real jobs their customers hire them to do can fall into the trap of providing one-size-fits-all solutions that ultimately satisfy no one.

-

Deeply understanding jobs opens up new avenues for growth and innovation by bringing into focus distinct “jobs-based” segments—including groups of “nonconsumers” for which an acceptable solution does not currently exist. They choose to hire nothing, rather than something that does the job poorly. Nonconsumption has the potential to provide a very, very big opportunity.

-

Seeing your customers through a jobs lens highlights the real competition you face, which often extends well beyond your traditional rivals.

- Questions for Leaders

- What jobs are your customers hiring your products and services to get done?

- Are there segments with distinct jobs that you are inadequately serving with a one-size-fits-none solution?

- Are your products—or competitors’—overshooting what customers are actually willing to pay for?

- What experiences do customers seek in order to make progress—and what obstacles must be removed for them to be successful?

- What does your understanding of your customers’ Jobs to Be Done reveal about the real competition you are facing?

-

What was stopping buyers from making the decision to move was not something that the construction company had failed to offer, but rather the anxiety that came from giving up something that had profound meaning. One interviewee talked about needing days—and multiple boxes of tissues—to clean out just one closet in her house in preparation for the move. Every decision about what she had enough space to keep in the new location was emotional. Old photos. Children’s first-grade art projects. Scrapbooks. “She was reflecting on her life,” Moesta says. “Every choice felt like she was discarding a memory.” That realization helped Moesta and his team begin to understand the struggle these potential home buyers faced. “I went in thinking we were in the business of new home construction,” recalls Moesta. “But I realized we were instead in the business of moving lives.” With this understanding of the Job to Be Done, dozens of small, but important, changes were made to the offering. For example, the architect managed to create space in the units for a classic dining room table by reducing the size of the second bedroom by 20 percent. The company also focused on helping buyers with the anxiety of the move itself, which included providing moving services, two years of storage, and a sorting room space on the premises where new owners could take their time making decisions about what to keep and what to discard without the pressure of a looming move. Instead of thirty pages of customized choices, which actually overwhelmed buyers, the company offered three variations of finished units—a move that quickly reduced the “cold feet” contract cancellations from five or six a month to one. And so on.

-

Everything was designed to signal to buyers: we get you. We understand the progress you’re trying to make and the struggle to get there. Understanding the job enabled the company to get to the causal mechanism of why its customers might pull this solution into their lives. It was complex, but not complicated. That, in turn, allowed the housing company to differentiate its offering in ways competitors weren’t likely to copy—or even understand. A jobs perspective changed everything

- Five ways to uncover jobs that might be right in front of you if you know what you’re looking for: seeing jobs

in your own life, finding opportunity in nonconsumption, identifying workarounds, zoning in on things we don’t want to do, and spotting unusual uses of products

- Finding a Job Close to Home. Understanding the unresolved jobs in your own life can provide fertile territory for innovation. Just look in the mirror—your life is very articulate. If it matters to you, it’s likely to matter to others. Take the example of Khan Academy founder Sal Khan’s initial amateur YouTube videos to help explain math to his young cousin. They weren’t even something new—there were hundreds of other online math tutorials on YouTube alone. Most of them looked and sounded better. “They weren’t using a USB headset like I was,” he recalls. “My version was cheap and dirty.” But there was one key difference. The other lessons felt complicated and pedantic. “They weren’t focusing on the core conceptual ideas—and they definitely weren’t fun,” he says. Not that his cousin could have told him that. “She was 12. I don’t know how introspective she was about the process,” he recalls. Khan’s cousin Nadia had found the way math was taught in her classroom at school stressful—as were the options of having her parents try their best to help her understand or asking the teacher for extra help. But with her cousin’s online videos, the stakes were low. Khan created his videos not simply to teach his cousin math, but to help him stay connected to his family and share his own love of learning. His cousin, on the other hand, hired his videos to feel successful by being able to learn complex math concepts in a way that was actually fun. Turns out there were lots of people who felt the same pain as his cousin. Today millions of students all over the world learn at their own pace through Khan Academy online. The good news is you don’t need to rely on personal inspiration to uncover a job that might provide a valuable innovation opportunity for your organization. You can learn a lot just by watching the customers you do—and don’t—already have. But you have to know what you’re looking for

- Competing with Nothing. You can learn as much about a Job to Be Done from people who aren’t hiring any product or service as you can from those who are. We call this “nonconsumption,” when consumers can’t find any solution that actually satisfies their job and they opt to do nothing instead. Too often, companies consider only how they can grab shares away from competitors, but not where they can find unseen demand. They may not even see it at all because existing data isn’t going to tell them where to find it. But nonconsumption often represents the most fertile opportunities, as was true for Southern New Hampshire University.Once a company shakes off the shackles of category-based competition, the market for a breakthrough innovation can be much larger than might be assumed from the size of the traditional view of the competitive landscape. You won’t see nonconsumption if you’re not looking for it.Chip Conley, Airbnb’s head of global hospitality and strategy, says that 40 percent of its “guests” say they would not have made a trip at all—or stayed with family—if Airbnb didn’t exist. And virtually all its “hosts” would never have considered renting out a spare room or even their whole home. For these customers, Airbnb is competing with nothing. A jobs perspective can change how you see the world so significantly that major new growth opportunities arise where none had seemed possible before. In fact, if it feels like there isn’t room for growth in a market, it could actually be a signal that you’ve defined the job poorly. There may be an entirely new growth opportunity right in front of you

- Workarounds and Compensating Behaviors. As an innovator, spotting consumers who are struggling to resolve a Job to Be Done by cobbling together workarounds or compensating behaviors, as Kimberly-Clark did with Silhouettes, should cause your heart to beat a little faster. You’ve spotted potential customers—consumers who are so unhappy with the available solutions to a job they very deeply want to solve that they’re going to great lengths to create their own solution. Whenever you see a compensating behavior, pay very close attention, because it’s likely a clue that there is an innovation opportunity waiting to be seized—one on which customers would place a high value. But you won’t even see these anomalies—compensating behavior and cobbled-together workarounds—if you’re not fully immersed in the context of their struggle. Frustrated by how ridiculously difficult—and financially punitive—banks had made the experience of opening a savings account for a child, I have a friend who actually went to the extraordinary lengths of setting up a symbolic “Bank of Daddy” to help his children understand the power of compound interest. The children’s allowance and pocket money never actually went into a bank—Mom and Dad just kept it for them—but every month the dad would credit their allowance to the account and calculate and add the interest they had accrued, paying a reasonable interest rate, unlike the real bank. It’s no surprise that many people have given up on savings accounts altogether. For decades, traditional banks had made it clear that the segment of “low net worth” individuals who wanted a simple savings account was undesirable. They were unprofitable in banks’ existing business models. So the banks did everything in their power to put them off: requiring minimum balances and charging fees and penalties for every conceivable service. My friend’s children, with their pocket money and presents from Grammy and Grampy, were not part of a segment banks wanted to attract. But that didn’t mean there wasn’t a rich opportunity to be mined. Enter ING Direct, which saw the market through a new lens. There was a complex Job to Be Done that had little to do with the function of saving money. In my friend’s case, he wanted to feel like a good father by helping his children understand the power of saving toward goals. ING Direct took away the obstacles. It’s an incredibly simple offering: The bank offers a few savings accounts, a handful of certificates of deposit, and mutual funds. The bank has no deposit minimums—you can open an account with a single dollar, if you want. It’s fast, convenient, and more secure than jamming tens and twenties into the back of a drawer, leaving them in birthday cards and forgetting about them—or calculating outsized interest rates at the Bank of Daddy. ING Direct needed a very different cost structure and business model if it was going to make money—but that was much easier to make work once it understood the job customers were trying to do. Everything about ING Direct corresponded to solving customers’ Jobs to Be Done: because it was an online bank, its operating costs were a fraction of those of brick-and-mortar competitors. And it also had none of the overhead costs of specialists for wealth management, loans, international services, and so on. That meant the focus on profitability and efficiency came from a completely different angle—not about the burden of supporting operating costs, but optimizing to solve customers’ jobs. ING Direct swiftly became the fastest-growing bank in the United States. Traditional banks should have had all the tools to capture this market, but they focused instead on segmenting customers instead of understanding their Jobs to Be Done. In 2012 ING Direct was sold to Capital One for $9 billion

- Look for What People Don’t Want to Do. I think I have as many jobs of not wanting to do something as ones that I want positively to do. I call them “negative jobs.” In my experience, negative jobs are often the best innovation opportunities. What parent doesn’t identify with this struggle: Your child wakes up with a sore throat. Your experience tells you it’s probably strep. You want your child to feel better and know that getting medicine in as quickly as possible is key, but gee, it’s really not a good day for this to happen. It’s a busy day at work, the child-care arrangements will be complicated, and the last thing you want to have to do is take time to get to the doctor for what probably will be a quick poke and prod to confirm what you suspect. If you call the pediatrician, he will, in good conscience, say he can’t prescribe anything without seeing your child. After finagling your way into an unscheduled appointment, you might sit in that waiting room for a long time until the doctor squeezes you in. Hours after that first call, when you finally get into the exam room, the doctor looks at your child, does a quick culture, and concludes it’s strep throat. He’ll call something into the pharmacy but you have to wait thirty minutes to pick it up. The whole afternoon is shot. In this case, the Job to Be Done is “I don’t want to see the doctor.” Harvard Business School alum Rick Krieger and some partners decided to start QuickMedx, the forerunner of CVS MinuteClinics, after Krieger spent a frustrating few hours waiting in an emergency room for his son to get a strep-throat test. CVS MinuteClinic can see walk-in patients instantly and nurse practitioners can prescribe medicines for routine ailments, such as conjunctivitis, ear infections, and strep throat. Because most people don’t want to go to the doctor if they don’t have to, there are now more than a thousand MinuteClinic locations inside CVS pharmacy stores in thirty-three states

- Unusual Uses. You can learn a lot by observing how your customers use your products, especially when they use them in a way that is different from what your company has envisioned. A story I often use to explain to my students how to find jobs that are hidden in plain sight is the case of Church & Dwight’s baking soda “category.” For nearly a century, the company’s iconic orange box of Arm & Hammer baking soda had been a staple in every American kitchen, an essential ingredient for baking. But in the late 1960s, management observed the diverse circumstances for which consumers grabbed that orange box off the shelf. They added it to laundry detergent, mixed it into toothpaste, sprinkled it on the carpet, or left an open box in the refrigerator, as well as other unusual uses. Until then, it hadn’t occurred to management that their staple product could possibly be hired for any job other than classic baking. But those observations led to a jobs-based strategy with the introduction of the first phosphate-free laundry detergent and a series of other highly successful new products, such as cat litter, carpet cleaner, air fresheners, deodorant, and so on.

- Today, we see the Arm & Hammer brand on a wide range of products—but each responding to a specific Job to Be Done:

- Help my mouth feel fresh and clean

- Deodorize my refrigerator

- Keep my swimming pool clean and fresh for me and my environment

- Help my underarms stay clean and fresh

- Clean and freshen my carpets

- Deodorize that stinky cat litter!

- Freshen the air in this room

- Remove shower stain and mildew

-

It’s not that these jobs were new—they’ve long existed. Church & Dwight just had to discover them. The orange-box baking-soda business is now less than 7 percent of Arm & Hammer’s consumer revenue; observing unusual uses has spawned millions of dollars in new product creations.

-

Some of the biggest successes in consumer packaged goods in recent years have come not from jazzy new products, but from a job identified through unusual uses of long-established products. For example, NyQuil had been on the market for decades as a cold remedy, but it turned out that some consumers were knocking back a couple of spoonfuls to help them sleep, even when they weren’t sick. Hence, ZzzQuil was born, offering consumers the good night’s rest they wanted without the other active ingredients they didn’t need.

-

When marketers understand the structure of the market from the customer’s Job to Be Done perspective, instead of through product or customer categories, the potential size of the markets they serve suddenly becomes very different. Growth can be found where none seemed possible before.

-

If a consumer doesn’t see his job in your product, it’s already game over. Even worse—if a consumer hires your product for reasons other than its intended Job to Be Done, you risk alienating that consumer forever.

-

Jobs Theory provides a clear guide for successful innovation because it enables a full, comprehensive insight into all the information you need to create solutions that perfectly nail the job.

-

There are many ways to develop a deep understanding of the job, including traditional market research techniques. While it’s helpful to develop a “job hunting” strategy, what matters most is not the specific techniques you use, but the questions you ask in applying them and how you piece the resulting information together.

-

A valuable source of jobs insights is your own life. Our lives are very articulate and our own experiences offer fertile ground for uncovering Jobs to Be Done. Some of the most successful innovations in history have derived from the experiences and introspection of individuals.

-

While most companies spend the bulk of their market research efforts trying to better understand their current customers, important insights about jobs can often be gathered by studying people who are not buying your products—or anyone else’s—a group we call nonconsumers.

-

If you observe people employing a workaround or “compensating behavior” to get a job done, pay close attention. It’s usually a clue that you have stumbled on to a high-potential innovation opportunity, because the job is so important and they are so frustrated that they are literally inventing their own solution.

-

Closely studying how customers use your products often yields important insights into the jobs, especially if they are using them in unusual and unexpected ways.

-

Most companies focus disproportionately on the functional dimensions of their customers’ jobs; but you should pay equally close attention to uncovering the emotional and social dimensions, as addressing all three dimensions is critical to your solution nailing the job.

- Questions for Leaders

- What are the important, unsatisfied jobs in your own life, and in the lives of those closest to you? Flesh out the circumstances of these jobs, and the functional, emotional, and social dimensions of the progress you are trying to make—what innovation opportunities do these suggest?

- If you are a consumer of your own company’s products, what jobs do you use them to get done? Where do you see them falling short of perfectly nailing your jobs, and why?

- Who is not consuming your products today? How do their jobs differ from those of your current customers? What’s getting in the way of these nonconsumers using your products to solve their jobs?

-

Go into the field and observe customers using your products. In what circumstances do they use them? What are the functional, emotional, and social dimensions of the progress they are trying to make? Are they using them in unexpected ways? If so, what does this reveal about the nature of their jobs?

-

Most companies want to stay closely connected to their customers to make sure they’re creating the products and services those customers want. Rarely, though, can customers articulate their requirements accurately or completely—their motivations are more complex and their pathways to purchase more elaborate than they can describe. But you can get to the bottom of it. What they hire—and equally important, what they fire—tells a story. That story is about the functional, emotional, and social dimensions of their desire for progress—and what prevents them from getting there. The challenge is in becoming part sleuth and part documentary filmmaker—piecing together clues and observations—to reveal the jobs customers are trying to get done.

-

Consumers can’t always articulate what they want. And even when they do, their actions may tell a different story. If I asked you if you care about being environmentally friendly, most of us would say yes. We’d talk about how we recycle or walk instead of driving whenever possible. But if I opened your cupboards, would they tell the same story? How many new parents do you know who say they care about climate change, but gratefully stock disposable diapers instead of cloth? Do you happily pop a plastic K-cup into your coffee machine? On the other hand, research has consistently shown that a significant portion of customers are willing to pay more for foods that are labeled “organic,” a word that is so generically used that it’s almost meaningless. What explains the disparity? No one aspires to be environmentally unfriendly, but when the actual decision to pull a product into your life has to be made, you pick the solution that best represents the values and tradeoffs you care about in those particular circumstances.

-

OK, so if what consumers say is unreliable, can’t you just look at the data instead? Isn’t that objective? Well, data is prone to misinterpretation. Sales and marketing data in the toy industry told Pleasant Rowland that girls between the ages of seven and twelve would never play with dolls. And most data only tracks one of the two important moments in a customer’s decision to hire a product or service. The most commonly tracked is what we call the “Big Hire”—the moment you buy the product. But there’s an equally important moment that doesn’t show up in most sales data: when you actually “consume” it.

-

The moment a consumer brings a purchase into his or her home or business, that product is still waiting to be hired again—we call this the “Little Hire.” If a product really solves the job, there will be many moments of consumption. It will be hired again and again. But too often the data companies gather reflects only the Big Hire, not whether it meets customers’ Jobs to Be Done in reality. My wife may buy a new dress, but she doesn’t really consume it until she’s actually cut the tag off and worn it. It’s less important to know that she chose blue over green than it is to understand why she made the decision to finally wear it over all other options. How many apps do you have on your phone that seemed like a good idea to download, but you’ve more or less never used them again? If the app vendor simply tracks downloads, it’ll have no idea whether its app is doing a good job solving your desire for progress or not.

-

Jobs to Be Done have always existed. Innovations have just gotten better and better in the way we can respond to them. So no matter how new or revolutionary your product idea may be, the circumstances of struggle already exist. Consequently, in order to hire your new solution, by definition customers must fire some current compensating behavior or suboptimal solution—including firing the solution of doing nothing at all. Wristwatches were fired in droves as soon as people began carrying mobile phones that not only told them the time, but could sync with calendars and provide alarms and reminders. I fired my weekly Sports Illustrated when I could suddenly flip on ESPN. The people who hired Depend Silhouette incontinence products fired staying at home instead of risking going out. Companies don’t think about this enough. What has to get fired for my product to get hired? They think about making their product more and more appealing, but not what it will be replacing.

-

A customer’s decision-making process about what to fire and hire has begun long before she enters a store—and it’s complicated. There are always two opposing forces battling for dominance in that moment of choice and they both play a significant role.

-

The forces compelling change to a new solution: First of all, the push of the situation—the frustration or problem that a customer is trying to solve—has to be substantial enough to cause her to want to take action. A problem that is simply nagging or annoying might not be enough to trigger someone to do something differently. Secondly, the pull of an enticing new product or service to solve that problem has to be pretty strong, too. The new solution to her Job to Be Done has to help customers make progress that will make their lives better. This is where companies tend to focus their efforts, asking about features and benefits, and they think, reasonably, that this is the roadmap for innovation. How do we make our product incredibly attractive to hire?

-

The forces opposing change: There are two unseen, yet incredibly powerful, forces at play at the same time that many companies ignore completely: the forces holding a customer back. First, “habits of the present” weigh heavily on consumers. “I’m used to doing it this way.” Or living with the problem. “I don’t love it, but I’m at least comfortable with how I deal with it now.” And potentially even more powerful than the habits of the present is, second, the “anxiety of choosing something new.” “What if it’s not better?”

-

The job has to have sufficient magnitude to cause people to change their behavior—“I’m struggling and I want a better solution than I can currently find”—but the pull of the new has to be much greater than the sum of the inertia of the old and the anxieties about the new. There’s almost always some friction associated with switching from one product to another, but it’s also almost always discounted by innovators who are sure that their product is so fabulous it will erase any such concerns. It’s easy to fire things that simply offer functional solutions to a job. But when the decision involves firing something that has emotional and social dimensions to solving the job, that something is far harder to let go. No matter how frustrated we are with our current situation or how enticing a new product is, if the forces that pull us to hiring something don’t outweigh the hindering forces, we won’t even consider hiring something new

-

So how can you begin to map out these competing forces to get to the crux of your customers’ jobs? Your customers may not be able to tell you what they want, but they can tell you about their struggles.

-

What are they really trying to accomplish and why isn’t what they’re doing now working? What is causing their desire for something new? One simple way to think about these questions is through storyboarding. Talk to consumers as if you’re capturing their struggle in order to storyboard it later. Pixar has this down to a science: as you piece together your customers’ struggle, you can literally sketch out their story.

-

You’re building their story, because through that you can begin to understand how the competing forces and context of the job play out for them.

-

Airbnb’s founders clearly understood this. Before launching, the company meticulously identified and then storyboarded forty-five different emotional moments for Airbnb hosts (people willing to rent out their spare room or entire home) and guests. Together, those storyboards almost make up a minidocumentary of the jobs people are hiring Airbnb to do. “When you storyboard something, the more realistic it is, the more decisions you have to make,” CEO Brian Chesky told Fast Company. “Are these hosts men or women? Are they young, are they old? Where do they live? The city or the countryside? Why are they hosting? Are they nervous? It’s not that they [the guests] show up to the house. They show up to the house, how many bags do they have? How are they feeling? Are they tired? At that point you start designing for stuff for a very particular use case.”

-

One of the critical storyboard moments, for example, is the first Little Hire moment for guests—when they first turn up at the home in which they’ll stay. How are they greeted? If they’re expecting a place that has been described as relaxing, is that evident? Maybe there should be soft music playing or a scented candle, says Airbnb’s Chip Conley. Has the host made them feel at ease with their decision? Has the host made clear how they will solve any issues or problems that arise during the stay? And so on. The experience must match the customers’ vision of what they hired Airbnb to do. The Airbnb storyboards—which have been constantly tweaked and improved since its founding—reflect the importance of the combination of pushes and pulls that drive their customers’ Big Hires and Little Hires.

-

The moments of struggle, nagging tradeoffs, imperfect experiences, and frustrations in peoples’ lives—those are the what you’re looking for. You’re looking for recurring episodes in which consumers seek progress but are thwarted by the limitations of available solutions. You’re looking for surprises, unexpected behaviors, compensating habits, and unusual product uses. The how—and this is a place where many marketers trip up—are ground-level, granular, extended narratives with a sample size of one. Remember, the insights that lead to successful new products look more like a story than a statistic. They’re rich and complex. Ultimately, you want to cluster together stories to see if there are similar patterns, rather than break down individual interviews into categories.

-

Deeply understanding a customer’s real Job to Be Done can be challenging in practice. Customers are often unable to articulate what they want; even when they do describe what they want, their actions often tell a completely different story.

-

Seemingly objective data about customer behavior is often misleading, as it focuses exclusively on the Big Hire (when the customer actually buys a product) and neglects the Little Hire (when the customer actually uses it). The Big Hire might suggest that a product has solved a customer’s job, but only a consistent series of Little Hires can confirm it.

-

Before a customer hires any new product, you have to understand what he’ll need to fire in order to hire yours. Companies don’t think about this enough. Something always needs to get fired.

-

Hearing what a customer can’t say requires careful observation of and interactions with customers, all carried out while maintaining a “beginner’s mind.” This mindset helps you to avoid ingoing assumptions that could prematurely filter out critical information.

-

Developing a full understanding of the job can be done by assembling a kind of storyboard that describes in rich detail the customer’s circumstances, moments of struggle, imperfect experiences, and corresponding frustrations.

-

As part of your storyboard, it’s critically important to understand the forces that compel change to a new solution, including the “push” of the unsatisfied job itself and the “pull” of the new solution.

-

It is also critical to understand the forces opposing any change, including the inertia caused by current habits and the anxiety about the new.

-

If the forces opposing change are strong, you can often innovate the experiences you provide in a way that mitigates them, for example by creating experiences that minimize the anxiety of moving to something new.

- Questions for Leaders

- What evidence do you have that you’ve clearly understood your customers’ jobs? Do your customers’ actions correspond to what they tell you they want? Do you have evidence that your customers make the Little Hire and the Big Hire?

- Can you tell a complete story about how your customers go from a circumstance of struggle, to firing their current solution, and ultimately hiring yours (both the Big and the Little Hires)? Where are there gaps in your storyboard and how can you fill them in?

- What are the forces that impede potential customers from hiring your product? How could you innovate the experiences surrounding your product to overcome these forces?

-

Uncovering a job in all its rich complexity is only the beginning. You’re a long way from getting hired. But truly understanding a Job to Be Done provides a sort of decoder to that complexity—a language that enables clear specifications for solving Jobs to Be Done. New products succeed not because of the features and functionality they offer but because of the experiences they enable.

-

When you see a company that has a product or service that no one has successfully copied, like American Girl, rarely is it the product itself that is the source of the long-term competitive advantage, something American Girl founder Pleasant Rowland understood. “You’re not trying to just get the product out there, you hope you are creating an experience that will do the job perfectly,” says Rowland. You’re creating experiences that, in effect, make up the product’s résumé: “Here’s why you should hire me.”

-

That’s why American Girl has been so successful for so long, in spite of numerous attempts by competitors to elbow in. My wife, Christine, and I were willing to splurge on the dolls because we understood what they stood for. American Girl dolls are about connection and empowering self-belief—and the chance to savor childhood just a bit longer. I have found that creating the right set of experiences around a clearly defined job—and then organizing the company around delivering those experiences almost inoculates you against disruption. Disruptive competitors almost never come with a better sense of the job. They don’t see beyond the product. Preteen girls hire the dolls to help articulate their feelings and validate who they are—their identities, their sense of self, and their cultural and racial background—and offer them hope that they can surmount the challenges in their lives. The Job to Be Done for parents, who are actually purchasing the doll, is to help engage both mothers and daughters in a rich conversation about the generations of women that came before them, and their struggles and their strength. Those conversations had disappeared as more and more women entered the workforce in the years after the women’s movement, and mothers and grandmothers were craving an opportunity to bring them back into their lives. The dolls—and their worlds—reflect Rowland’s nuanced and sophisticated understanding of the job. There are dozens of American Girl dolls representing a broad cross section of profiles. For example, there’s Kaya, a young girl from a Northwest Native American tribe in the late eighteenth century. Her back story tells of her leadership, her compassion, her courage, and her loyalty. There’s Kristen Larson, a Swedish immigrant who settles in the Minnesota territory and faces hardships and challenges but triumphs in the end. There’s modern-era Lindsey Bergman who is focused on her upcoming bat mitzvah. And so on. A significant part of the allure is the well-written, historically accurate books about each character’s life that express feelings and struggles that the preteen owner might be sharing. The books may be even more popular than the dolls themselves. Rowland and her team thought through every aspect of the experience required to perform the job very, very well. The dolls were never sold in traditional toy stores, thrown in the mix alongside any number of competitors. They were initially available only through a catalog, then later at American Girl stores, which were initially created in a few major metropolitan areas. It turned out this added to the experience, turning a trip to the American Girl store into a special day out with mom (or dad). American Girl stores have doll hospitals that can repair tangled hair or fix broken parts. Some of the stores have restaurants in which parents, children, and their dolls can happily sit and be served from a kid-friendly menu—or host birthday parties. The dolls become the catalyst for experiences with mom and dad that will be remembered forever. No detail was too small to consider for its experiential value. That familiar red-and-pink packaging that the dolls come in? Rowland designed them with a clear window of the doll inside, but they were wrapped with what’s known as a belly band—a narrow wrapper around the whole box—and the dolls were packed in tissue paper. That belly band, Rowland remembers, added two cents and twenty-seven seconds to the actual packaging process itself. The designers suggested they simply print the doll’s name right on the box itself to save time and money—an idea Rowland rejected out of hand. “I said you’re not getting it. What has to happen to make this special to the child? I don’t want her to see some shrink-wrapped thing coming out of the box. The fact that she has to wait just a split second to get the band off and open the tissue under the lid makes it exciting to open the box. It’s not the same as walking down the aisle in the toy store and picking a Barbie off the shelf. That’s the kind of detail we tended to. I just kept going back to my own childhood to the things that made me excited.” American Girl was so successful in nailing the Job to Be Done of both mothers and daughters that it was able to use its core offerings—and the loyalty they established—as a platform to expand into what might seem to be wildly diverse fields. Dolls, books, retail stores, movies, clothes, restaurants, beauty parlors, and even a live theater in Chicago, all of which Rowland actually had in mind before she launched the company. They simply made intuitive sense to her—based on the happy experiences of her own childhood—and aligned squarely with the job. Going to the live theater for an American Girl show? That harkened back to the days when she used to put on white gloves to go to Chicago Symphony concerts with her own mother. “That was a moment I was trying to re-create for girls when they went to the American Girl store. It was very much coming out of my life experience,” she explains. “I simply trusted my memories of childhood.” Three decades after its launch, there’s a generation of American Girl fans who are now adults and eager to share the dolls—and the experiences they enable—with their own children. We have a family friend who still buys American Girl dolls for her adult daughter at Christmas with the express wish that she hands them down to her own daughters someday. Under Mattel’s ownership, it has seen a slight dip in sales in the past couple of years, but no one has been successful in unseating American Girl from its perch. “I think nobody was willing to put the depth in the product to create the experience,” says Rowland. “They thought it was a product. They never got the story part right.” To date, no other toy manufacturer has been able to copy American Girl’s magic formula.

- A deep understanding of a job provides a sort of decoder to the complexity—a job spec, if you will. Whereas the job itself is the framing of the circumstance from the perspective of the consumer with the Job to Be Done, as he or she confronts a struggle to make progress, the job spec is from the innovator’s point of view: What do I need to design, develop, and deliver in my new product offering so that it solves the consumer’s job well? You can capture the relevant details of the job in a job spec, including the functional, emotional, and social dimensions that define the desired progress, the tradeoffs the customer is willing to make, the full set of competing solutions that must be beaten, and the obstacles and anxieties that must be overcome. That understanding should then be matched by an offering that includes a plan to surmount the obstacles and create the right set of experiences in purchasing and using the product. The job spec then becomes the blueprint that translates all the richness and complexity of the job into an actionable guide for innovation. Designed without a clear job spec, even the most advanced products are likely to fail. There are just too many details to nail and tricky tradeoffs to be made in creating customer value for innovators to rely on the luck of just guessing right. The experiences you create to respond to the job spec are critical to creating a solution that customers not only want to hire, but want to hire over and over again. There’s a reason successful jobs-based innovations are hard to copy—it’s in this level of detail that organizations create long-term competitive advantage because this is how customers decide what products are better than other products.

-

IKEA is one of the most profitable companies in the world and has been so for decades. Its owner, Ingvar Kamprad, is one of the wealthiest men in the world. How did he make so much money selling nondescript furniture that you have to assemble yourself? He identified a Job to Be Done. Here’s a business that doesn’t have any special business secrets. Any would-be competitor can walk through its stores, reverse-engineer its products, or copy its catalog. But no one has. Why not? IKEA’s entire business model—the shopping experience, the layout of the store, the design of the products and the way they are packaged—is very different from the standard furniture store. Most retailers are organized around a customer segment or a type of product. The customer base can then be divided up into target demographics, such as age, gender, education, or income level. There are competitors who sell to wealthy people—Roche Bobois sells sofas that cost thousands of dollars! There are stores known for selling low-cost furniture to lower-income people. And there are a host of other examples: stores organized around modern furniture for urban dwellers, stores that specialize in furniture for businesses, and so on. IKEA doesn’t focus on selling to any particular demographically defined group of consumers. IKEA is structured around jobs that lots of consumers share when they are trying to establish themselves and their families in new surroundings: “I’ve got to get this place furnished tomorrow, because the next day I have to show up at work.” Other furniture stores can copy IKEA’s products. They can even copy IKEA’s layout. But what has been difficult to copy are the experiences that IKEA provides its customers—and the way it has anticipated and helped its customers overcome the obstacles that get in their way. Nobody I know relishes the idea of spending a day shopping for furniture when they really, really need it right away. It’s not entertainment, it’s a frustrating challenge. Factor in that your children will likely be with you when you’re shopping and it could be a recipe for disaster. IKEA stores have a designated child-care area where you can leave your children to play while you wind your way through the store—and a café and ice cream stand to offer as a reward at the end. Don’t want to wait to get your bookshelves home? They’re flat-packed in cartons that can fit in or on most cars. Is it daunting to lay out all the parts to an unbuilt book-shelf and then have to put it together yourself? Absolutely. But it’s not overwhelming because IKEA has designed all its products to require just one simple tool (that’s included with every flat pack—and actually stored inside one of the pieces of wood so you can’t accidentally lose it when you open the box!). And everyone I know who has tackled an IKEA assembly ends up feeling pretty proud of himself or herself when it’s done.

-

Who is IKEA competing with? My son Michael hired it when he moved to California to start his doctoral studies: “Help me furnish my place today.” He’s got to decide what he’ll hire to do the job. So how does he decide? He has to have some kind of criteria to make his choice. At a fundamental level, he will factor in how much he cares about the basics of the offering: cost and quality, and the priorities and tradeoffs he’s willing to make in the context of the job he needs to get done. But he’ll care even more about what experiences each possible solution offers him in solving his job. And what obstacles he’d have to overcome to hire each possible solution. He’ll hire IKEA, even if it costs more than some of those other solutions, because it does the job better than any alternatives. The reason why we are willing to pay premium prices for a product that nails the job is because the full cost of a product that fails to do the job—wasted time, frustration, spending money on poor solutions, and so on—is significant to us. The “struggle” is costly—you’re already spending time and energy to find a solution and so, even when a premium price comes along, your internal calculus makes that look small compared with what you’ve already been spending, not only financially, but also in personal resources. Other furniture stores might offer Michael free delivery, but it will probably take days or even weeks to deliver the furniture he wants to purchase. What is he going to sit on tomorrow? Craigslist offers bargains, but he’ll have to cobble together his furniture choices and rent a car to drive all over town to get them, probably enlisting a friend to help him lug them up and down the stairs. Discount furniture stores might offer some of IKEA’s benefits, but they’re not likely to be so easy to assemble at home. Unfinished furniture stores have decent quality products, but you have to paint them yourself! That’s not easy to pull off in a small apartment. He’s not likely to feel good about any of these other choices.

-

You can only shape the experiences that are important to your customers when you understand who you are really competing with. That’s how you’ll know how to create your résumé to be hired for the job. And when you get that all right, your customers will be more than willing to pay a premium price because you’ll solve their job better than anyone else. I should clarify, however: sometimes customers get pushed into paying for premium products because they’re interdependent with a product that they have already hired to solve a job in their lives. Think about the eye-popping price tag for printer-ink cartridges. Or smartphone rechargers or cases. We’ll give in and pay the premium price because there isn’t a better solution at the moment, but we will simultaneously despise the company for taking us to the cleaners. These products actually cause anxiety, rather than resolve it. I hated having to monitor how much color ink my kids were using on our home printer. I don’t like worrying about misplacing a charger. This is not what I mean about premium prices that customers are willing to pay. By contrast, with jobs-based innovations, customers don’t resent the price, they’re grateful for the solution.

-

Products that succeed in solving customers’ jobs essentially perform services in that customer’s life. They help them overcome the obstacles that get in their way of making the progress they seek. “Help me furnish this apartment today.” “Help me share our rich family history with my child.” Creating experiences and overcoming obstacles is how a product becomes a service to the customer, rather than simply a product with better features and benefits.

- Medical-device manufacturer Medtronic learned this the hard way when it was trying to introduce a new pacemaker in India.

On the surface, it seemed like a market full of potential, because, unfortunately, heart disease is the country’s number one

killer. But for a variety of reasons, very few patients ever ended up opting for a pacemaker to solve their medical problem.

For years, Medtronic had relied on traditional forms of research to develop its product offerings. “We were very good at understanding

functional jobs,” recalls Keyne Monson, then senior director of international business development at the medical device manufacturer.

For example, when Medtronic was looking to improve its pacemakers, it assembled panels of doctors to pick their brains about

what they’d like to see in the next generation of the devices. The company then fielded quantitative surveys that validated

the physician panels’ feedback and new products were created. The new versions of Medtronic’s pacemaker were clearly superior, but unfortunately they didn’t sell in India as well as the

company had hoped. It had been nagging at Monson for some time that neither the qualitative nor quantitative approaches Medtronic

had historically relied on had actually answered the question of why people would want to hire a pacemaker and what obstacles might get in their way—and to do so for the broader set of stakeholders

involved. With the lens of Jobs to Be Done, the Medtronic team and Innosight (including my coauthor David Duncan) started research afresh

in India. The team visited hospitals and care facilities, interviewing more than a hundred physicians, nurses, hospital administrators,

and patients across the country. The research turned up four key barriers preventing patients from receiving much-needed cardiac

care:

- Lack of patient awareness of health and medical needs

- Lack of proper diagnostics

- Inability of patients to navigate the care pathway

- Affordability

-