Rising to Power - Ron A. Carucci

Note: While reading a book whenever I come across something interesting, I highlight it on my Kindle. Later I turn those highlights into a blogpost. It is not a complete summary of the book. These are my notes which I intend to go back to later. Let’s start!

-

If we think in very basic terms, all organizations take inputs and transform them into outputs. Depending on the life-stage and maturity of the organization, an individual role may be required to play in multiple systems, as in start-ups or high-growth environments. In such cases, the need is even greater for leaders to be consciously aware of which role(s) they are acting in and why. Successful companies identify clear and distinct contributions for leaders in the operating system, Coordinating system, and the strategic system of the organization. Knowing what these expected contributions are, and demonstrating that knowledge in how you fulfill your role as a leader, is a big part of being an effective contributor in the system in which you participate.

-

The Operating system is all about execution. It plays a central role in the delivery of goods and services to the market. Those participating in this system are responsible for taking raw inputs and converting them into whole, consumable outputs that are valued and used by end-user consumers or by other organizational processes. Ultimately, the majority of the effort and resources of any organization should be allocated to directly support the Operating system, and in return, an effective Operating system commits to the following: Adapt and learn. Individual and collective effort is expended to acquire competency and increase proficiency to deliver the company’s core value proposition to the market. Use resources effectively. Understanding of the strategy and priority objectives is leveraged to manage and allocate resources to achieve both top- and bottom-line results. Communicate upward. Given the hands-on connection with the work, the Operating system is uniquely positioned to raise issues and offer insights about the practicalities of executing the stated strategy and objectives. Reinforce desired behavior. The Operating system has the largest population and therefore exacts the greatest impact on the culture.

- The Coordinating system has four primary accountabilities:

- Translate strategy: Strategies can only be enacted when they have personal meaning for individuals in the enterprise. Coordinating roles ensure that the strategy moves from a theoretical concept into how people must work and add value in order to achieve the strategy.

- Allocate and manage: They ensure clear trade-off choices and actively manage how finite resources are used to increase the probability of success.

- Transfer knowledge and skill: They elevate and amplify the capacity of the Operating system and develop next-generation talent.

- Reinforce the operating philosophy: They enact the desired culture by consciously modeling and holding each other accountable to the values and behavioral standards defined by the company.

-

Perfect definition of roles in the Coordinating system: working in the system to get things done.

- While people in the Coordinating system work in the system to get things done, leaders in the Strategic system work on the system itself. This becomes apparent when you think about the work of the roles in the Strategic system:

- Monitor external trends: Identify opportunities and mitigate threats.

- Define the competitive position: Set strategic priorities and define accountability of the company relative to competitors.

- Secure and allocate capital: Make the challenging trade-off calls for funding and resource support at the enterprise level.

- Define corporate values: Articulate the values and behavioral standards that shape the operating environment for all employees.

- Define and evolve the organization: Proactively identify the need to adapt the enterprise to meet strategic objectives and manage change.

- Develop senior enterprise talent: Establish and actively manage an integrated talent management system to improve leadership capacity and ensure continuity.

-

The biggest failing of people in the Strategic system is getting bogged down in the minutia of the business. Every large organization is complex, with an almost infinite number of crises competing for your time and having the potential to drag you down and make it hard to see the bigger picture. Most in the organization lack your vantage point, however, and count on you to help them see the bigger picture. If you are down in the weeds then nobody has the whole picture, and this can be terribly dangerous for your organization. If, on the other hand, you maintain the appropriate altitude and get involved only occasionally in things you think are important for the big picture, it will send a very powerful message to the rest of the organization.

-

People need space and autonomy to do their jobs, make decisions, solve problems, generate ideas, make mistakes, and learn from them. It doesn’t matter if you think your ideas are “better” or if they come “faster.” As long as everyone understands the strategy and is working in the right context, your job is to let them do their jobs. Defining the strategy and the context in which they operate is your job. You need to support your people without micromanaging. This is harder in the Strategic system than it is in the Coordinating system because your direct reports have far greater spheres of control. The temptation to intervene can be overwhelming. But unless there is a compelling reason for you to get involved, trust your people to do it themselves and support them in their work both in what you do—and don’t—say and do.

-

We once asked a semiretired leader whose judgment we respected how he knew he needed to get personally involved in an issue. He simply said, “Honor necessity.” How do you know you’ve done enough, we pressed. “Honor sufficiency,” he replied. We’ve thought about this over the years, and have come to appreciate these simple measures. There are times when you will need to get involved to resolve issues in the other systems of the organization. Indeed, in some instances, you will be the only one with sufficient perspective and authority to resolve conflicts and find solutions. Do this when it is necessary, and don’t flinch from it. If you have picked your battles wisely, your involvement will send a strong message. But bear in mind the dictum “honor sufficiency” as you go. Resolve what must be resolved and then let your people take over the next steps. Remember that you are here to make a difference. You may inadvertently undermine the very impact you hope to make by choosing inappropriate issues in which to involve yourself. When in doubt, ask yourself, “Does my involvement in this issue directly advance the impact I am hoping to make, or just solve a problem more quickly than if I let others handle it?”

-

Your words have far greater resonance in the Strategic system—and so does your silence. One leader we spoke with was amazed at how quickly the rumor mill took over when he did not provide information. He was preparing to announce a merger and had gone for a few weeks unable to comment on some confidential negotiations under way. He was dismayed by the stories people made up and spread to fill the gaps created by his uncharacteristic silence. Another executive was shocked to find that simple rides in the elevator resulted in multiple people believing they had landed the same top job on his senior team. He actually hadn’t promised anyone anything, or at least he hadn’t meant to. Another form of word choice comes when you must confront or disappoint, critical at the strategic level. Being direct, never mincing words, and calling hard questions are more critical than ever, less your “smoothing over” or “pulling punches” reinforce actions and beliefs you need changed. Watch what you say and what you omit—there are no “casual” utterances now.

-

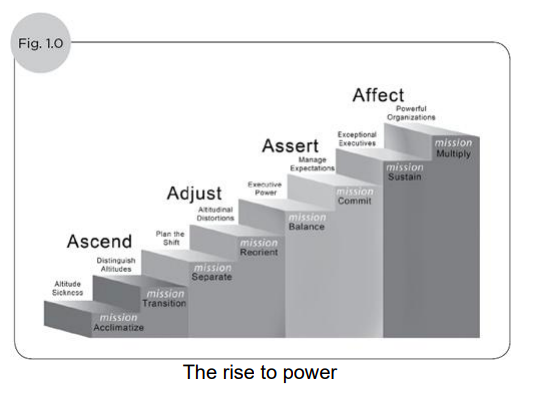

Understanding the three systems of the enterprise—the Strategic, Coordinating, and Operating systems—is really about understanding the realities of your role in the context of the scale you’ve taken on. Despite the personal experience and expertise leaders can draw on as they rise to the Strategic system, many find this the hardest transition of their careers, and not all get the hang of it. Your mandate is now quite different. You are not just a Really Big Manager—you are a leader in every sense of the word. You are responsible for creating the strategic context in which the people in the other systems function. You have a broader and longer view than others in the organization and you have the ability to set the course for the enterprise. You can now reshape the organization in ways no one else can. It is important that you keep the scope and scale of your role in perspective. You can do things that no other person can do, which means that if you spend too much of your time on Coordinating system tasks, your job will simply go undone, to the detriment of your business. True, this becomes more challenging when your new organizational peers interpret their strategic roles more tactically than you need to. Still, make the conscious choice to play at the level your organization needs. Your success and the success of all your people depend on it.

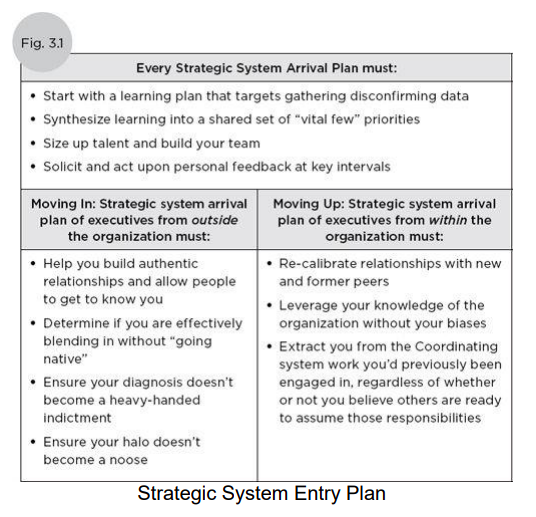

- An effective executive enters the Strategic system as a true anthropologist—setting aside preconceived hypotheses about what she will discover and genuinely seeking to “learn” the organization and its people. The relevance of anthropology is significant, because it distinguishes itself from other social sciences through its emphasis on the in-depth examination of context. The way people make sense of the world around them and the relationships they form among themselves are at the heart of social and cultural anthropology. Such a study is foundational to the success of an executive’s entry. The notion that this can be done even in ninety days is foolish, but keeping an open mind for at least that long while allowing new ideas and assumptions to form, and building factual conclusions about the context and its people, will take you much further in the long run than “hitting the ground running” with foregone conclusions that later prove unsound. Here’s why. A savvy executive understands that she is not just sizing up the organization for what she can or needs to change. She is also sizing up how she will need to change, and how the organization will change her in the process. Most leaders don’t even register that part. They enter under the presumption of change agent, not change beneficiary or potential change casualty. So while clarity of your aspirations will help you stay clear on what your impact will be, prematurely deciding that impact based on what you’ve been told or what you assume is dangerous. The early days are the time to suspend judgment about what value you came to create long enough to truly learn what difference is possible and what it will require of you to make it.

-

Regardless of their former role, most executives arrive with a plan for how to assess the organization they are entering and a set of assumptions about what they will find. The headhunter and/or hiring manager has given them data. If they are being promoted from within, they certainly have a sense of the organization’s history. That has all informed their thinking. If arriving from outside, they’ve done their own research with data in the public domain. With such an array of information on hand, it’s natural to already have one’s mind nearly made up about the state of the organization and what you need to get done.

-

Having gathered substantive data, including disconfirming data to offset your assumptions, you now need to construct an initial set of priorities around which to focus and align the organization. Newly appointed executives often forget that their arrival is a disruptive jolt for the organization. It sets people off balance as they speculate about what changes the leader will make, how those changes will depart from the predecessor’s agenda, and how those changes will affect them personally. Anxious conjecture drains the organization of focus and needed energy for the leader’s plan. Leaders who understand the context before they give the organization its marching orders know that less is often more, simplicity equals clarity, and setting up small wins parlays into needed momentum and bigger wins later. Leaders who fail to understand this reveal grand plans that paralyze the organization with too many priorities, and bury everyone under the weight of massive work in addition to their day jobs.

- One of the hardest aspects of rising to an executive role is inheriting your predecessor’s team. It would be great if everyone on the team had to “re-up” for their job, but unfortunately that’s generally not the case. A lot of factors influence whether or not the existing team is the right team for you and the direction in which you will take the organization:

- their track record of performance,

- how receptive they are to your leadership,

- how overtly they try to curry favor with you,

- how subtle they are about throwing their teammates under the bus when sharing their views on “what’s got to change,”

- how capable they are of delivering against the results you need, and

- how genuinely they resonate with the vision you are forming.

-

Whatever criteria you use, you must form a systematic way to assess the talent you have against the agenda you are forming to determine who can stay, who can grow, and who must go. Most newly appointed executives are reluctant to make hard calls, especially early in their tenure.

-

Calibrating how effectively your entrance is going is critical to ensuring it doesn’t derail before you know it’s in trouble. The lagging indicators for whether or not you are getting traction are insufficient and unreliable for determining if you are “sticking” or not. This is especially important in your first six months, when people are still forming impressions of you and your network is unformed (meaning your data sources are limited). Whether through an online survey tool, or a third party’s interviews, you must have a reliable barometer to know if the messages you are sending, the vision you are casting, the leadership you are modeling, the plans to which you are holding people to account, and the changes you are initiating are all being metabolized as you intend. Feedback loops that help you quickly determine where you are on course and where you aren’t allow you room to maneuver and course correct.

-

Regardless of how much of a “fit” you believed your new organization would be, you are still an outsider. And people will make up things about you as an outsider in the absence of real information. But you have some control over what they make up. The degree of transparency with which you reveal important aspects of your life—your personality, your values, appropriate information about your family, and the degree to which you express interest about those aspects of the lives of others—has a great deal of influence on your credibility and the degree to which people trust you.

-

Though occasionally executives entering the higher strata can be like bulls in china shops with lots of bravura and declarations of “a new era,” most instinctively know those entrances are often short-lived and ill-fated. More commonly, executives default to the opposite side of the spectrum, walking on eggshells: being overly cautious not to ruffle any feathers or “offend” anyone. Ironically, this often has the same consequence as the charging bull—it still offends and alienates people. Leaders get so caught up in trying to “read the environment” that they become excessively inward-focused at the expense of truly “seeing” what is around them. Their self-involved myopia leads them to squander opportunities with those to whom they want to build bridges, and to behave as anything but themselves.

- One of the most perplexing discoveries executives rising into the Strategic system from within their organization make is that of a reconfigured peer set. It can literally make them feel like they’ve arrived on a different planet. First, those who are no longer peers—some of whom may now be direct reports—treat you differently than they used to, uncertain how much they can now trust whether or not “you’re still you.” Then there are those with whom you are now a peer, more experienced executives who’ve learned to navigate the political waters of the Strategic system. These leaders have learned who their nemeses are, who their allies are, and with whom they are competing for the hallowed next rung up that corporate ladder. You feel like the proverbial stranger in a hostile, foreign land, longing for the trusted peers of the land you left behind. You have two dilemmas. Those relationships with former peers can serve you every bit as well as they always have, but you must redefine how they will work in the context of your new role. The relationship with your new peers takes on increased importance, yet is consistently one of the most common derailers of executive careers the higher they rise.

-

How to identify the key players within the organization: those people that control budgets and those that supply goods or services. However, to succeed, a new executive also needs to identify the various alliances that exist, the opinion makers, and the people with expert knowledge or influence. All too often, identifying such people is left to the skills of the new appointee, rather than being part of the induction process.” Failure to build relationships is one of the key factors Davis cites as driving the 40 percent failure rate within eighteen months among newly appointed senior executives.

-

The Operating and Coordinating systems of the business reward a sharp focus on execution and paying attention to the biggest hurdles to making your numbers. We refer to this as the “tyranny of the urgent.” In the Strategic system, the tyranny of the urgent translates into putting out fires without any awareness of a bigger picture. The head of the North American operations arm of a global consumer products company came to us because he was being criticized as being “incapable of action.” Yet he was a very busy guy, traveling all over the United States and Canada and making numerous decisions every day. How could he be seen as “incapable of action”? We accompanied him for a few days and took note of what he actually spent his time doing. He was on a dawn-to-dusk fire drill, addressing one small crisis after another all over his organization. He was very popular among all the regional heads. They had a terrific relationship with him and felt they could call him whenever, wherever they needed him. They knew he would bail them out. But this was the head of all North American operations. None of the strategic work the global CEO and board expected of him was getting done. As we dug deeper, we found that many of the function heads also complained of numerous unresolved issues. They couldn’t even get on his calendar because he was so involved with addressing smaller “urgent” matters. His inability to shift away from the tyranny of the urgent almost cost him his position.

- Maintaining steady focus instead of being impulsive and reactionary allows you to become the North Star for your people and organization. Your people need to know that the hurdles they’re clearing are all aligned and taking them in a direction that achieves the results the strategy calls for. Markets are volatile—people will get knocked off course. You need to keep your sense of direction and your sense of proportion.

-

One executive at a technology company we were supporting had a tendency to weigh in on every decision, even minor ones. The unintended consequence of this is that he divested his senior staff of decision-making authority and ultimately capability. The company quickly determined that it could not make any decisions without him and as a result, had become glacially slow. Get involved where you should—and where you feel you must. But choose wisely.

- Taking on one of the top positions in an organization is similar—you can study it, talk to people who do it, and observe it in action, but until you are sitting in the chair it is very difficult to anticipate how you will respond. New senior executives often report feeling this free-fall sensation: Your past experience is all on the ground and doesn’t necessarily provide the best guidance for how to “leap from the plane.

-

Talented cinematographers understand the power of perspective. They exploit the angle of the camera to manipulate our emotions. George Lucas effectively established Darth Vader’s menacing character by taking the six-foot-seven David Prowse, who played him, and shooting him from a low angle, amplifying his already imposing presence. Alfred Hitchcock pulled us into the dark world of Norman Bates by consistently shooting the house from a low angle, causing us to feel small and anxious. By virtue of your role and its position in the organizational hierarchy, those at lower levels see you from a similar low vantage point that can distort their perspective of you. How others see you changes significantly as you rise. You take on the persona inherent to your position, which may or may not reflect who you are or how you want people to see you. Some people will revere you; others will actually fear you. The demands of your job will often make you less physically present and accessible to some, and people will naturally fill in the resulting voids with stories of their own. Many of the senior executives we’ve coached have been surprised when they realized that people were making stuff up about them. Remember, by virtue of your role, your presence is felt no matter how accessible, inaccessible, close, or distant you are. This is in part due to the phenomenon of embodiment. Sitting atop a function or a business, you embody your organization. If you lead Marketing, for example, to the rest of the organization, you are Marketing. If you lead the West Division, or the Apparel Division, you are the West Division or the Apparel Division. Don’t resist this reality; it comes with the territory. Still, don’t allow the role or others to completely define you. You must work to prevent a default persona from becoming the way people see you. Be thoughtful about how accessible you are, and when necessary take steps to increase that access with key individuals or groups. Provide insight into what you value and believe; share the essence of who you are and your vision for the role. Consciously incorporate that in both formal and informal meetings, what and how you write, and the stories you tell. As your sphere of responsibility and influence grows, so will your reputation. The higher up you are, the more your reputation matters, and the further outside your direct control it becomes. It will take on a life of its own, entering every room before you do. Your name will be bandied about in offices and break rooms across the company and be on the lips of people you’ve never spoken to. Rest assured, everyone will have an opinion about who you are. You won’t be able to control everything people believe, and you shouldn’t make yourself crazy trying; however, if you are not deliberate about what others see and how people experience you, chances are the image they form will be one that you do not intend or desire.

-

The larger-than-life view of you has an important corollary that we call “the megaphone effect.” Imagine that you speak through a massive bullhorn 24/7. This image is truer than you might realize. The verbal and behavioral messages you send are amplified the moment you step into your new elevated role. Newly appointed senior executives from vastly different industries—one in digital media and the other from a global deep-earth mining organization—said essentially the same thing to us only weeks apart: Both found people kept trying to read the future from their off-the-cuff remarks. “I’m just trying to make small talk in the elevator and I’ve got this creepy feeling they’re looking at me like the prophet Elijah,” one of them said sadly. “Every time I open my mouth someone attaches meaning to it. I keep hearing people say ‘Bill said,’ and it is generally to bolster their own case. The ‘Bill said’ phenomenon is rampant, attributing things to me that I not only never said, but never even thought.” When you are one of the top leaders in your organization—and certainly when you become CEO—there is no “small talk.” It becomes difficult for people to separate you from the role. You can certainly still talk to people—don’t become stiff and formal—but always keep in mind how people experience you. Try to be as clear as you can about your intentions and as precise as possible in your communication. A little forethought goes a long way. We call this “leading out loud,” and we constantly find ourselves coaching newly appointed executives both on the need for it and how to do it effectively. One wise respondent aptly said, “Never take the power of your position for granted. Comments, suggestions, even audible pauses, hold much more weight and meaning now.” Take note: This is very different from “thinking out loud.” One senior leader we worked with had a propensity to think out loud about possible directions his group could take. He shared his thoughts about a number of potential opportunities at the end of one particular meeting, but left the room believing everyone had ended with the same “that’s nice but now it’s back to our day jobs” feeling he had. He was alarmed several weeks later when his group came back to him with a detailed proposal in support of one of the “pipe dreams” he had talked about briefly. They’d researched, developed a presentation, built a budget, and clearly spent a lot of time working on it. He was mortified. He’d had no intention of ever going in this direction and had certainly not wanted people taking up valuable time to explore it. Having to talk his people down from the excitement they had for the opportunity and clarify the misunderstanding was one of his most uncomfortable leadership moments. This is not uncommon. Leaders often launch significant initiatives and work efforts without ever intending to, simply by sharing their musings. If you are not clear in what you are saying, why you are saying it, and to whom, don’t be surprised when people pick up on fragments and amplify or misinterpret them as directives. As one respondent astutely advises, “I must be careful what I say and in what context. People read more into what I say than I intend. People may drop priorities if I casually express interest in things outside their objectives. My voice must retain focus so they can retain their focus.”

-

Take stock of how information flows within the larger context of the business. Regardless of personal style or your previous expectations regarding participation, how information flows to and through your new level is largely influenced by a broader set of historic assumptions already in play. If promoted within the same organization, you at least have the advantage of knowing the key hubs of information brokering. You know the typical conversations that occur before meetings with senior leaders, how information is edited, rationed, and choreographed in the room, and what typically happens afterwards. The difference is that you may now be on the receiving end of this orchestrated behavior. While you may feel uneasy, there is a silver lining in not having access to all that you did previously. It dramatically reduces the risk of your focus being diverted to levels of detail that are now someone else’s primary concern. You will need to determine what information is most valuable in light of your new responsibilities and, using prior knowledge, consider how you might influence and work within known organizational patterns to access it. Information is a currency of influence in all organizations. When you are new to an organization, you must quickly identify the key power brokers and begin to establish a quality working relationship with them. Even from positions of high influence, it is good to recognize you won’t have total control over well-established operating norms. We have observed many senior-level executives enter new organizations expecting full access to information, only to find they have access to the data, but those who can bring the nuanced story and understanding to light have gone underground. Understand the important implications of information as a source of executive power.

- No greater distortion will occur for newly arriving executives—especially those promoted from within—than in their existing relationships with peers and superiors. Former peers may now become direct reports, or at least remain at lower ranks. Former superiors become the new peer set where relational dynamics must also shift. Relationships once characterized by comfortable familiarity may now seem alien and others’ reactions to you may be equally foreign and confusing.

-

However subtle or pronounced their individual views of and reactions to you are, you should proceed with the assumption that things are not, and will not be, the same. They simply can’t be. Even though you won’t believe you’ve changed personally—and you probably haven’t—the situation and your leadership responsibilities have; therefore, successful rising executives make a conscious effort to reset expectations and boundaries with existing relationships at each new elevation. They first define for themselves and then deliberately discuss with colleagues things such as new priorities, access, frequency of contact, information flow, confidentiality, and appropriate ways to influence. It may feel awkward, but by resetting these expectations and clarifying boundaries you will free yourself from wondering about and disappointing others’ privately held views and expectations of you and your new role. One executive we know was so painfully insecure leading her former peers that she went out of her way to neutralize any sense of hierarchical difference. While well intended, she did such a good job of self-comforting by reassuring everyone that “nothing was really going to change between them”—like the weekly lunch ritual they long shared—that when it came time to make hard decisions and hold volatile information with discretion, she failed. The luncheon became her stage for “going native” and complaining to her old friends with newfound frustrations, burdening them by disclosing highly inappropriate information and colluding with them when it came to justifying underperformance. During enterprise talent calibrations, her team did not fare well, and her attempts to defend them only made her look weak and out of touch. She padded the delivery of hard messages with, “I don’t agree with these ratings, but here’s where you came out in the mix …” Despite her attempts to distance herself from the messages, team members felt betrayed and quickly withdrew their loyalty. Within a year her department had devolved into such chaos that the business unit president was forced to break it up and reorganize the work. She was moved to a smaller role and, though she retained her “rank,” her influence and impact were clearly diminished. To date, her career has not regained the momentum it had when she took on her executive role.

- Being thoughtful and deliberate about focusing your best efforts on developing positive partnerships with key stakeholders is vital to success at any level; however, building effective working relationships with peers is increasingly critical the higher you move up the organization. In fact, it is our observation that the strength of your peer relationships will be the strongest predictor of your sustained success as you rise. Certainly you must be competent in your functional discipline, but if you struggle to get along with and relate to your peers, you will soon find yourself mired in and distracted by unhealthy rivalry and political posturing and eventually being marginalized.

-

Identify who are the key individuals with whom you must develop effective working relationships. Then, subordinate your own wants and needs and ask yourself: What motivates them? What critical goals and key milestones are they trying to achieve? By what standard will they judge success? What challenges might they be facing? How can I contribute to their success? Take notes of your hypothesis and be observant, and then meet with them individually to find out. When you meet, tell them that you want to be an effective partner to them, and focus the conversation on getting answers to your questions. Throughout the conversation, also try to discover what they look for in an effective partner, how they prefer to communicate, and any “hot buttons” they might have that would trigger a negative reaction. Listen carefully to the questions they ask of you and consciously gauge whether they initiate any form of politicking. If so, you must risk the relationship by calling the question and establishing clear boundaries of expectation up front. Return the focus to your sincere desire to support their success, but not at any price. Reserve judgment or making commitments until after you’ve met with all of your key partners. Give yourself the benefit of a little time to assess the full picture of need before jumping in. We know several executives who maintain a spreadsheet containing the names of their partners with answers to each of the questions above. They carry them together with their own objectives as a constant reminder of the priorities they should be working.

-

Loyalty is particularly important in the relationship with your boss. Ensure that you clearly understand and align with her vision and objectives. Advocate for her agenda where appropriate, but be an independent thinker. Spar supportively on ideas to make them better. Be transparent. Share any hard news early, and never surprise her. Don’t be afraid to ask for help, but leverage her air cover judiciously. Give her no reason to doubt your motives and allegiance. At the same time, don’t let your loyalty be confused with a level of accommodation that suggests you are buying favor. The conditions for your loyalty should be based on the worthiness and commitment to your partner’s cause, not on what she returns for it. If you are seen as overly deferent, not only will your loyalty be questioned, but so too will your credibility as an executive able to stand on your own.

-

BE TRUSTWORTHY AND TRUSTING, BUT NOT NAIVE: Trust is foundational to all human relationships. Building trust of an enduring nature requires effort as it is built and reinforced by consistent action and focused energy over a sustained period of time. Hard work, time, and energy, and some degree of risk taking, are required if people are to reap the full potential for satisfaction and productivity in their interpersonal relationships. Rising executives must particularly focus on building trust with peers and key partners. The highest leverage effort you can make toward success in any endeavor involving interdependent relationships is to become trustworthy. It is a trait admired and sought after globally. For trust to grow, you must consciously work at earning the right to be trusted. Becoming a trustworthy executive depends on your competence and the consistent results you deliver, as well as the integrity of your character—the way you achieve those results. Your character is revealed in the way you communicate and stand up for what you believe in, honor your commitments, speak honestly and transparently without guile, admit mistakes, apologize when needed, keep confidences, be fair and show diplomacy when dealing with others, and forgive and move on. As you’ve likely experienced, the ability to deepen trust demands hard work, and yet destroying it can happen in one moment of lapsed judgment.

-

Trust is foundational to all human relationships. Building trust of an enduring nature requires effort as it is built and reinforced by consistent action and focused energy over a sustained period of time. Hard work, time, and energy, and some degree of risk taking, are required if people are to reap the full potential for satisfaction and productivity in their interpersonal relationships. Rising executives must particularly focus on building trust with peers and key partners. The highest leverage effort you can make toward success in any endeavor involving interdependent relationships is to become trustworthy. It is a trait admired and sought after globally. For trust to grow, you must consciously work at earning the right to be trusted. Becoming a trustworthy executive depends on your competence and the consistent results you deliver, as well as the integrity of your character—the way you achieve those results. Your character is revealed in the way you communicate and stand up for what you believe in, honor your commitments, speak honestly and transparently without guile, admit mistakes, apologize when needed, keep confidences, be fair and show diplomacy when dealing with others, and forgive and move on. As you’ve likely experienced, the ability to deepen trust demands hard work, and yet destroying it can happen in one moment of lapsed judgment. As trust grows, interpersonal dynamics will be positively transformed. Diverse skills and abilities become mutually acknowledged and valued as strengths. Positive attitudes and feelings toward each other increase. Communication becomes more efficient and clear. Candor increases as people more confidently offer differing opinions and disconfirming data absent any fear of offending or retribution. They risk conflict to push each other to deeper communication, involvement, and commitment because they believe the others’ motives are pure. Just as trust creates a positive multiplier effect by its mere presence, its absence has an equally debilitating impact. Always keep in mind the fragile nature of trust. It can be destroyed quickly. Just one misguided action can erase the bond that has taken years to build. Once trust is betrayed, a predictable and destructive pattern of suspicion and diminished confidence emerges. It is noteworthy that attempts to restore trust are more challenging than the effort required to initially gain it, and seldom is it restored to its previous state.

-

One of the biggest hurdles many executives face as they rise to the rank of executive is shifting from seeing themselves as problem-solvers to pattern recognizers. In the Strategic system you need to see patterns in the marketplace, patterns in how your organization responds, patterns in how groups operate, and patterns in how people behave. You need to evaluate and respond to patterns at a systemic level instead of responding to a particular instance outside of the greater context. Like the images hiding in stereograms, organizational patterns sometimes don’t appear until you squint enough and seemingly unrelated dots suddenly connect.

-

Heifetz, author of Leadership on the Line and No Easy Answers, defines leadership as “the ability to disappoint people at a rate they can absorb.” Newly appointed executives must have sufficiently thick skin to withstand the inevitable disappointment and emotional residue that comes with unpopular decisions. It is a significant portion of the job, and to avoid it under the illusion of getting everyone “on board” and dispersing accountability only serves to heighten risk.

-

Many leaders today are torn between wanting to direct and wanting to include. The result is a muddled form of leadership that is little more than benevolent manipulation. We call it faux inclusion. You invite leaders into a room under the ruse of participating in a decision you’ve already made, engage them in what appears to be open discussion, subtly (or so you think) steer the conversation in the direction you want, and the moment anyone hints at an option mirroring the direction you’ve privately selected, you pile on with grand reinforcement, sealing the deal. People see right through it now, and this form of exploitation can be damaging to trust and engagement. Some leaders accustomed to this form of inclusion stop showing up for meetings.

-

The moment someone discovers that disclosing information to you is a liability, everyone you work with will know it. Treat all sensitive information you get from others as sacrosanct.

-

Leaders who fail to provide sufficient transparency into their decision-making criteria and approaches known in advance of actually making decisions are at risk for owning those decisions alone. Letting people know on the front end what criteria you intend to use and how you intend to make the decision will go a long way to building support. While many executives often fear being overly declarative in their decision making, the fact is followers find it liberating when leaders simply say, “I’m making the call and here’s how I’m going to make it.” Contrary to popular organizational mythology, followers do not expect to be involved in every single decision that touches them. And it would be cruel to expect them to participate in decisions they are neither equipped nor experienced enough to make. Be clear when you are asking for input for a decision that you will ultimately make. When you intend for a decision to be reached by consensus, make that clear. When you are delegating the authority for making a decision to others, and do or don’t want to offer any input, make that clear. And when you are just making the call, be clear about that as well.

-

What followers want is a sense of predictability. They want to be able to decode your analytical process, your moral compass, and your trade-off criteria when making tough decisions. They want to be able to predict, with a reasonable sense of accuracy, how you will behave in a given situation. When they can’t predict, it is too easy to assume that you are hiding something. This leads them to fear your political motives, question who may have curried favor with you, wonder about the disaster you are working privately to stem, or speculate what plot you are devising against them or another organizational nemesis. Head such “Kremlin watching” off at the pass by providing a consistent and clear approach to decision making that sustains followers’ confidence by allowing them to reasonably forecast how your leadership is going to show up at critical decision junctures.

-

What followers really want from their executives is reliability. They need to know that if they have problems, you’ll be there to help them find solutions. If there’s something they can’t make sense of, you’ll offer helpful perspective. If they can’t get someone in an adjacent department to cooperate, you’ll run interference. While the amount of time you spend doing these things will obviously vary from person to person, when followers conclude that you aren’t reliable, the amount of time you don’t spend with them becomes the issue. While you can’t—and don’t want to—become everyone’s answer ATM, and you need to build self-sufficiency among those you lead, knowing you are there as a resource to guide, support, challenge, admonish, and just plain help bolsters their trust in your leadership and helps them more effectively decide when and how to engage you most effectively.

-

Followers need a reason to maintain hope. They need to know that what lies beyond the horizon of their perspective is a reason to keep going, and they need to know you sense what that reason is. In a truthful and balanced way, they need to hear from you the realism of what is, and the optimism of what could be.

- Governance, at its most elegant, is refreshingly simple. You need: the right people, equipped with the right data and authority, making the right decisions aligned against agreed-upon priorities, allocating the appropriate resources, determining the right steps to execute. Sadly, most organizations fail to construct governance models closely linked to strategy execution. Truth is, the integration of strategic, financial, and talent processes that allocate authority, priorities, and resources in the service of executing strategy is one of the most profoundly differentiating activities a company can undertake. It is the very lever, when pulled, that can deliver the efficiency, effectiveness, and results that optimize a company’s competitive positioning. Most organizations—of all sizes—tend to believe they have a governance model without ever having applied a comprehensive and intentional review of what it is and how it works. Some small and mid-sized companies think that governance is a concern for large organizations only. They operate more “organically” and pride themselves on being “an informal company.”