The McKinsey Engagement - Paul N. Friga

Note: While reading a book whenever I come across something interesting, I highlight it on my Kindle. Later I turn those highlights into a blogpost. It is not a complete summary of the book. These are my notes which I intend to go back to later. Let’s start!

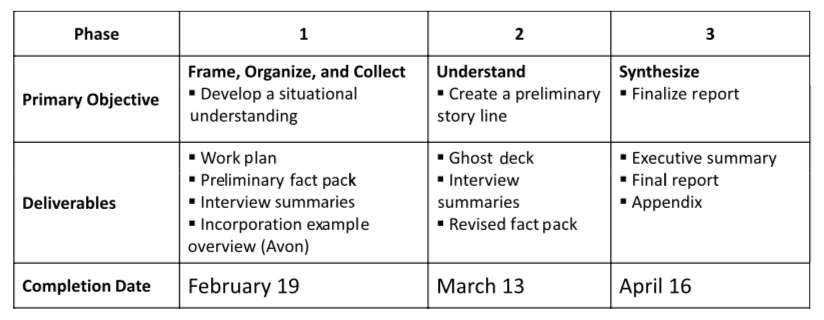

- TEAM FOCUS Model

- TALK—One of the most important elements of high-quality team problem solving is establishing very clear channels of communication. This chapter discusses special communication tools and provides guidance concerning best-process communication, inclusion of important constituents outside of the core team, and tips on managing interpersonal dialogue. The chapter also features a special section about listening.

- EVALUATE—Teamwork is a dynamic process, and the most successful teams are those that are able to assess their current level of performance and adapt accordingly. The starting point for good evaluation is an open dialogue about expectations, group norms, specific work processes, and tools for monitoring progress. Implicit in the team evaluation process is an individually based personal plan that allows each team member to grow and develop on a continual basis. We all have strengths and weaknesses, and evaluation is the only way in which we can adequately identify where to focus our energy for improvement.

- ASSIST—Once the evaluation process is underway, the next critical phase of the teamwork process is assisting others to complete the team’s objectives. This builds on the Evaluate phase, which identifies particular strengths of team members that can be leveraged for the good of the team. Strategic leverage of unique capabilities is an underlying component of all “special forces” organizations and is just common sense. At the same time, team members must hold one another accountable for their assigned responsibilities. Direct, honest, and timely feedback will ensure that the Assist process is operating correctly.

- MOTIVATE—The last element of the model’s interpersonal component involves very specific strategies for motivation. One of the most important considerations is the realization that team members are motivated by different factors. Accordingly, engaging in informal, candid conversations at the beginning of the project about what those unique motivators are and paying close attention to individuals’ drivers will go a long way. Similarly, the best teams are those that provide positive recognition for individual contributions and take adequate time to celebrate as a group (many of us seem to do less and less of this the older we get). The second component of the model relates to the core analytical elements of successful project management. The word itself is conveniently right on target: FOCUS.

- FRAME- The first element in the FOCUS component is widely regarded as the most important in the entire model. Essentially, framing the problem (before you begin extensive data collection!) involves identifying the key question that you are studying, drawing issue trees for potential investigation, and developing hypotheses for testing during the project. Good framing translates into more effective problem solving, as you will be ensuring that the work you are doing will translate into high-impact results—the ultimate measure of effectiveness.

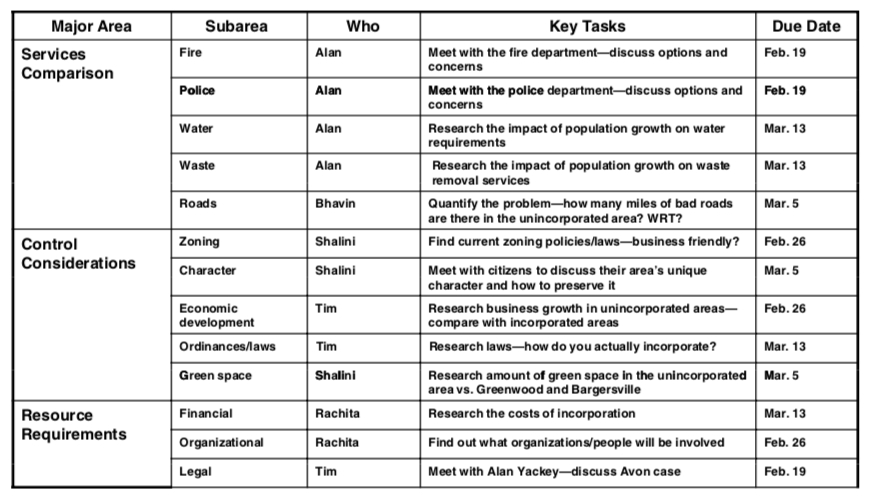

- ORGANIZE—This element is a boring but necessary step in preparing the team for efficient problem solving. All teams organize in some manner or another, but my research suggests that more efficient teams organize around content hypotheses with the end in mind. Unfortunately, in many cases, there seems to be a default approach that compels teams to organize quickly around the buckets that seem to surface most easily, rather than on the basis of potential answers to the key question under study.

- COLLECT—The next element of the model provides guidance that leads to the collection of relevant data, avoiding the overcollection of data that are not useful. The most efficient teams are those that can look at the two piles of data collected and smile as they realize that the relevant data (pile 1) far outweigh the irrelevant information (pile 2) because the team continuously analyzed the difference.

- UNDERSTAND—As the team gathers data, these data must be evaluated for their potential contribution to proving or disproving the hypotheses. At McKinsey, the term used on an almost daily basis is “so what?”—what is the meaning of the insight from these data for the project, and ultimately for the client?

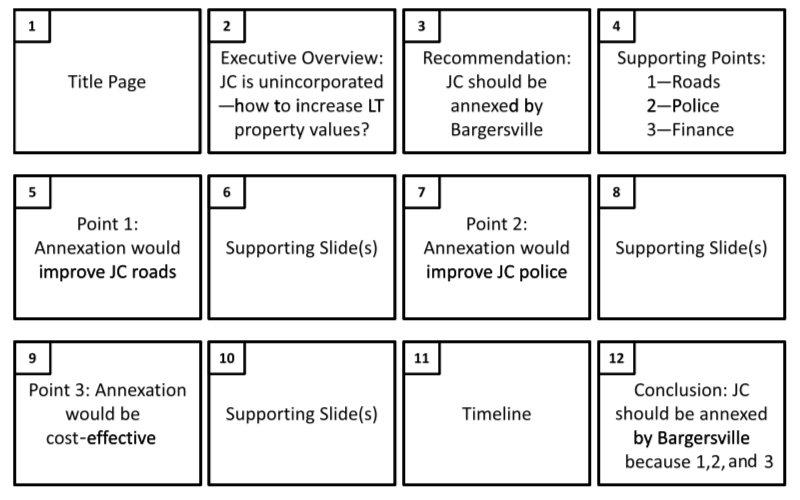

- SYNTHESIZE—The final element in the model is to synthesize the information into a compelling story. Here is where the well-known “pyramid principle” related to organizing a written report or slide deck comes into play.

-

The costs of undercommunication far exceed those of overcommunication.

-

One particular weakness that continues to gnaw at me—and some of you may suffer from it as well—is cutting people off in the middle of their sentences. I like to think it is because I am smart enough to figure out where they are going, but indeed it is just rude! A critical Rule of Engagement is for everyone on the team to learn how to listen attentively. McKinsey provides specific training on how to become a better listener. It advocates a number of techniques in this area, and four specific tips stand out to me as worthy of repeating: Let go of your own agenda—at least for the time being—and don’t interrupt. Focus on the speaker. Physically look at the speaker, maintain eye contact, and give him or her your undivided attention. Encourage the speaker, both verbally and nonverbally (e.g., through body language). Discuss the content. Summarize it, paraphrase it, and demonstrate understanding of it.

-

One more idea related to listening is to actively solicit opinions and ideas from those on a team who have not yet contributed. This is especially important for the quieter or more introverted members of the team.

- Some of our keys for successful interactions during the project are outlined here:

- Structure: Providing topics for discussion before each meeting and pulling in the key stakeholders meant that meetings tended to be more effective in terms of problem solving and time savings. (Decision meetings were heavily, if not exclusively, fact based.) Structure led to preparation, where attendees could digest the topics and come prepared to ask or field questions.

- Clear communication: Straight talk, active listening, and pushing to keep dialogue logically driven steered discussions away from black-and-white, binary, culturally driven responses (e.g., yes or no), and more toward “yes” or “what needs to be done to make the answer yes?”

- Frequency:Holding meetings on a regular basis improved overall communication and kept various parts of the organization up to date (especially given team locations in Canada and China). Frequency of meetings with attendees from varying levels in the corporate hierarchy also provided visibility for project owners, a showing of support to the midlevel managers from upper management, and time savings for all parties involved.

- The Operating Tactics for the Talk element of the TEAM FOCUS model are:

- Document and share all contact information for the entire internal and external team, identify the key communication point players (who will contact whom), and define the overall scope of the project.

- Agree on a meeting schedule that matches the nature of the project, but try to meet in person as a full team at least weekly (include the client in some meetings), or daily for one- to two-week projects.

- All meetings should have a clear agenda (or list of issues to discuss), produce specific deliverables, and result in new action plans.

- Use e-mail frequently to keep the team updated on progress, and use a brief and consistent format. Remember that overcommunication is better than undercommunication.

- When evaluating the pros and cons of issues and ideas, remember to separate the issue or idea from the per- son (once an issue or idea is presented, everyone evaluates it on its merit without any personal attachment to it).

- There are three critical success factors for a good evaluation system within a team (note that we are not discussing overall firm evaluation systems here, although there are certainly similarities):

- Openness. All of the team members must have an interest in receiving feedback on their performance.

- Explicitness. While evaluative processes are often helpful, there must be explicit conversations about the intent and process of evaluation to make it most effective.

- Agreement. Before an evaluation takes place (before any feedback, actually), there should be agreement between the sender and the recipient as to the objectives of the evaluation and the measures for it.

- The starting point for a good team evaluation culture is to have an open and casual discussion about the team’s use of evaluation tools. At McKinsey, this is a strongly suggested step (in fact it was mandatory) during the team project. It is usually manifested in the form of a kickoff conversation, a midpoint check, and an “after-action” review (although the last phase is sometimes captured in the individual evaluations).

- The Operating Tactics for the Evaluate element of the TEAM FOCUS model are:

- Identify the personality types of the team members (including the client).

- Hold a brief, relaxed session at the outset of the project to discuss personalities and working preferences. Keep the dialogue open over the course of the project.

- Be aware of your default tendencies, but incorporate the flexibility to deal with different personality types as needed.

- Each team member should identify and document his or her one or two primary objectives in the project.

- The team should openly discuss and reconcile individuals’ personal objectives.

- Establish procedures for handling disagreements and giving and receiving feedback.

- Hold regular feedback sessions to allow time for improvement.

- Clearly, we had our hands full in terms of handling the diversity of backgrounds, especially given the short time frame of the project. From day one, the team got off to a great start. We met in the McKinsey Paris office and covered the structure and the approach for the project. After discussing the project details in the office, we headed out to a bistro on the Champs-Elysées to discuss team dynamics, including self-introductions, individual work styles, Myers-Briggs, and so on. I knew that this step would be very important to ensure that the team members would get along, learn from one another, and deliver on high expectations. Each person had a critical role in the process, and we had to spend some time getting to know each other and the roles we would play on the project.

- Experience and research suggest that there are typically three key areas where issues arise related to providing adequate assistance during a team problem-solving project.

- Confusion over roles. The most common problem is that after the team is formed, assignments are doled out very quickly, without giving much thought to everybody’s capabilities and interests—a common mentality is to “just divide this up and get started.”

- Feedback not provided (or not provided well). If any of us really want to develop and grow, we need to receive feedback. The problem is that we don’t really want to hear about our weaknesses (these days it seems like we prefer to call these “opportunities for improvement”), or, more important, the messages are delivered in an awkward or personal way that makes them hard to digest.

- Overfocus on our own assignments. We all tend to prioritize our tasks based upon maximizing the benefits to ourselves, and as a result, we often lose sight of whether or not our teammates need help.

-

You have to (or should) take an inventory of team members’ skills (what they have done) and wills (what they would like to do), and have an explicit conversation about assignments. In essence, do an assessment based upon the respective education, work experience, and personal experience of everyone on the team.

- After the inventory, the team should then venture into a “roles” discussion. Who is going to be responsible for what on this project? Generally, high-level roles that people play on teams (especially in business schools) boil down to two categories: process and content.

- Process Roles “Big picture person.” This team member focuses on the overall story of the project and the presentation. “Deliverables driver.” This person keeps track of the time and the status of deliverables. “Communicator.” This person is the one primary point of contact with clients. “Devil’s advocate.” This team member ensures that alternative views are considered. “Touchy feely.” This is the person who continuously checks the morale of the team.

- Content Roles “Functional expert.” People in this role concentrate on strategy, marketing, finance, operations, or some other area. “Relationship guru.” This team member focuses on the relationship with external constituents. “Voice of experience.” This is someone who has worked on a similar project in the past.

-

One of the paramount operating practices for team members at McKinsey is ownership. Ownership means that each person on a team, from the brand-new business analyst to the most senior partner on the engagement, knows the big picture of the project (its mission and objectives) and knows how he or she fits in. Not only is the overall puzzle picture clear, but each person takes ownership of a piece of that puzzle. This is an important concept, because each person on a team should be doing something of value and contributing to the team’s overall success. The other positive by-product is that the other team members are aware of what each person is working on, what deliverables are anticipated, and when to expect them. Another major principle within this Rule of Engagement is the importance of deadlines. I will describe the use of content and process maps to guide engagements. For now, I think we can all relate to how important deadlines are to getting things done. In fact, deadlines are the backbone of the consulting process, as they give targets for the time by which a certain analysis must be completed. Deadlines also drive efficiency, as there is a tendency to add work to fill the available time; our goal is to force ourselves and our teams to be sure that everything that we are doing is adding value and having an impact on the end product for the client. Deadlines also give us a chance to reconnect with our teams to review the status of the pieces that each person owns and how the overall story is coming together. Every engagement has a mix of “individual” and “team” time, and the deadlines ensure that we have adequate (but not too much) team time to allow multiple perspectives and inputs for the “ideation.” It is also during the team time that we can review the current workload and assignments to ensure that our efforts are equitable and are continuing to contribute in a meaningful way to the overall direction of the project. However, this is a fine line, as we don’t want to micromanage the process, and we must trust our teammates to complete their assignments adequately. The Russian proverb that Ronald Reagan was fond of repeating is very fitting in these types of situations: “Trust, but verify.”

-

The most important aspect of effective feedback is that it must be delivered in a timely manner. This means that we must all share and receive feedback during and not just after the engagement. Postmortem feedback (especially in terms of after-action reviews) is helpful, but the more meaningful feedback comes during the project. This gives the person receiving the feedback a chance to work on improvement during the life of that particular engagement and minimize the negative effect of whatever the person is not doing well. Feedback should also generally be done in private. There may be times when a team does a group-sharing session, especially if it is facilitated by a third party. Most of the time, however, feedback is better delivered in private, and it should be presented in a non-threatening and helpful way.

- When delivering feedback, be sure to include some praise of a positive contribution before delivering the negative comment. A few recommendations for the feedback process follow: Deliver balanced feedback. Be specific; don’t generalize (e.g., “you are not a good problem solver”). Report from your perspective, not everyone’s (e.g., “I react a certain way when you . . .”). Provide examples of the causation and impact. End with a positive outlook and offer ideas for improvement and assistance.

- The Operating Tactics for the Assist element of the TEAM FOCUS model are:

- First spend at least an hour in a general brainstorming session to openly discuss the problem and key issues to explore

- Be sure to balance the load equitably based upon the estimated number of hours required to complete the tasks. Periodically revisit the assignments after work has begun to ensure that the work distribution continues to be equitable.

- Identify and leverage the specific skill set of each team member (and the firm or the client, if applicable

- Include at least one or two key status report meetings with the team (and the client) to review findings, data sources, and work streams.

- On a daily basis, provide an update of individual and team progress to assess opportunities to adjust workloads and assignments.

-

The suggested word choice for sharing feedback is along the lines of: “I have observed that . . .; the effect on me is . . .;” pause, “what I suggest is..

-

The benefits of celebrations are widely known but often forgotten. Good energy knows no bounds and feeds off itself. A celebration is a chance to focus on the positive outcomes of a project, such as client impact, achievement of personal objectives, and joint learning. Holding a postcompletion celebration should be a standard operating procedure. To McKinsey’s credit, it is normally very generous in supporting such activities; many times, the celebrations are bigger and better than you might imagine. I remember post-engagement celebrations that included limousines, golf outings, fancy dinners, Arizona retreats, spa treatments, and the like.

- The Operating Tactics for the Motivate element of the TEAM FOCUS model are:

- Identify and discuss one primary and one secondary motivator for each person (the source of energy for that team member).

- Give praise for and celebrate each major team milestone; share compliments with team members on a daily basis.

- Have a social gathering after the project is complete.

-

From a system dynamics perspective, framing is especially critical because all subsequent activities are connected to the conclusions reached during this process. If you fail to identify the right question or if you formulate misguided hypotheses, the best-case scenario will be that the team is inefficient, but it eventually gets the right answer. The worst-case scenario is that the team is both inefficient and ineffective, as it arrives at the wrong answer and is slower to get there than would otherwise be the case.

-

IDENTIFY THE KEY QUESTION At first glance, this first Rule of Engagement may appear to be quite simple and obvious, and you may be tempted to move on to the second rule quickly. This is the exact reaction that causes so many problems in the framing process of engagements. Team members are tempted to just get this step out of the way without giving it much thought and move on to the collection of critical data. However, the exact wording of the key question is critical for the analysis portion of an engagement. Rarely does the first cut at the key question prove to be successful; several iterations are usually required before a team defines the question well. The starting point is the client (or the case in a business school setting) and what it says the problem is. The complication is that the client may sometimes be focusing on a symptom or by-product rather than on the core issue.

- So how do we find the key question? The first step is to meet with representatives of the client to understand their perspective and their thoughts on the key question. Remember that the initial attempt to formulate this question may not be exactly right. It is important to make sure that the key question is at the right level of aggregation for the project and the desired outcomes. For example, “How can our organization survive?” is very different from, “How can we improve profitability?” or “How can we generate new business?” The differences lie in scope and specificity—shorter projects must either be more specific or require a lower level of supporting data for their conclusions. After the initial conversations, the brainstorming process can begin. The starting point, of course, is to list the suggestions from the client and the team members and begin to sort through this list to eliminate redundancy. It is also likely that some of the ideas are subsets of others, so you want to group related ideas. Shown here is a starting point for key questions in business, but you need to realize that the actual key question will be client-and project-specific. Note also that this is a functional framing—there are other ways to view the key question as well (e.g., level, geography, or time).

- What is our position in the market (and is it differentiated)?

- What are our organization’s priorities (and what should we not do)?

- What are our organization’s payments (and are they based on priorities)?

- What is our organization’s performance (vis-à-vis the competition)?

- What is our unique selling proposition (and do our customers want it)?

- How much should we charge for our products?

- How do we best communicate our offerings?

- How should we spend our media budget?

- How do we deliver on our business model?

- How do we reduce manufacturing costs?

- How do we increase throughput?

- How do we add capacity?

- How much do we pay our employees?

- Do we have the right stuff?

- How do we increase employee satisfaction?

- How do we ensure compliance with all regulations?

- How do we value our company?

- How do we obtain funds for expansion?

- How are we performing?

- Remember, the key question may or may not be functionally driven. It is always contingent upon the nature of the project.

-

Once the key question has been clearly articulated, the next step is to create an issue tree that will help organize the analysis of options.

- There are essentially two types of issue trees: information trees and decision trees. The starting point is the information tree, which is used to quickly get a sense of the situation under investigation.

-

The information tree is basically a listing of the key pieces of the current situation. Another way to think of this is that the information tree should summarize, “What is going on?” whereas the decision tree asks, “What can we do?”

-

Essentially, MECE is a way of organizing any list in such a way that it has “no gaps and no overlaps.”

-

Once the MECE issue tree has been constructed, the next step is the prioritization of the issues for investigation. This is a common breakdown point for many teams. The easiest approach is to allocate resources evenly across all the issues in the issue tree (in project management, the resource that is allocated is time and occasionally money). This is a very bad idea. The issue tree should be prioritized for analysis based on the key question and the decision criteria that would contribute to maximizing the impact of the ultimate recommendations for the client.

-

The final and most exciting part of the Frame element is the development of hypotheses. Hypotheses are potential answers to the key question. The hypothesis becomes the starting point for the decision tree. If the hypothesis is true, what else needs to be true? Since the origin of this approach is the scientific method, we must remember that the hypothesis must be falsifiable; this means that it must be specific and able to be proved or disproved with data. An example of a poor hypothesis would be, “The company should improve its operations”—this is not specific enough to be proven true or false. A better example is, “The company should double its capacity, increase employee annual bonus programs, and cut its product line by 33 percent.” Note that there is likely to be more than one ultimate recommendation for any given project.

-

Also, while the hypotheses ultimately become recommendations by the end of the engagement, they are simply hypotheses in the Frame stage, as they are not yet proven.

-

How long should teams spend on the Frame process? I have developed a rule of thumb to answer this question: Approximately 5 percent of an engagement’s total time should be spent on framing (assuming that the project time frame is three months or less). So, assuming a three-month project with 360 hours of analysis time, the framing should be finished in about 18 hours or 2 days. In terms of deliverables, this means that the key question has been identified, the issue trees have been drawn out, and the hypotheses have been specified. This ratio can hold true for a 24-hour business school case competition as well, which would mean that the team should complete the framing within 1 to 2 hours. Note again that the process is iterative, and we fully expect adjustments to the initial hypotheses. My last thoughts on framing are warnings. First, be very careful when communicating hypotheses to clients or others outside the team. I have learned the hard way that if a client believes that you think you can solve a complex business problem in 5 percent of the project time, that client will get nervous. The term hypothesis is not generally understood across the board, and it can be interpreted as your proposed answer. It is better to communicate the ideas as potential areas to explore, about which to get the client’s input, and ultimately to test with data. One other warning is to remember that this process takes time and you are not expected to nail the solution so quickly. It is helpful to have a direction for testing, but remember to keep an open mind, to seek dis-confirming evidence, and not to become personally attached to a hypothesis that you proposed!

- The Operating Tactics for the Frame element of the TEAM FOCUS model are:

- Identify the key question that drives the project, which should be based upon specific discussions with the client.

- Document this question, the scope of the project, and the high-level plan of attack in an engagement letter.

- Specifically identify the temporal (years under study), geographical, and functional areas for the project.

- Avoid the common problem of “scope creep,” where additional work is added that is beyond the original parameters of the engagement or is only tangentially relevant to them. Refer back to the base problem, parameters, and engagement letter to mitigate scope creep.

- Develop a general hypothesis that is a potential answer to the problem at hand.

- Develop supporting hypotheses that must be true to support the general hypothesis (for testing).

- Revisit and revise the hypotheses during the project as data are gathered (prove or disprove the hypotheses and if necessary develop new ones).

-

Several weeks into a project, the project team helps client management define its real key question. Sisto Merolla, an ex-McKinsey consultant from Italy, describes a common scenario in which a client fails to frame a problem properly, especially in terms of identifying the key question. In my experience, framing is the most important part of a project. One of my clients was an electric utility that asked McKinsey to evaluate potential acquisition targets. Some weeks into the engagement, after several interviews with the top managers, we discovered that the real question the company was struggling with was, “Is our generation plants portfolio in line with the future evolution of electricity market prices?” Once we understood this, we were able to engage the CEO in a very fruitful discussion about what seemed the most likely evolution of the electricity market and what actions could be taken. We came to the joint conclusion that the company did not need to acquire other players immediately, and that the first urgent move was to stop the construction of two new plants. These two additional plants would have imbalanced the generation portfolio, tilting it to an excess of gas-fired plants, which was very dangerous and was not aligned with the corporate strategy. Sometimes the value that McKinsey adds is helping clients’ top managers to take a higher view and understand the “real” issue instead of rushing into the first solution that comes to mind.

-

Once the problem is framed properly, we need to organize our analysis efforts in a very strategic manner. Remember that our primary goal in this process is both increased effectiveness (doing the right thing) and increased efficiency (doing it well). The underlying assumption here is that many team problem-solving adventures could be improved. What are the typical issues associated with nonstrategic approaches to team problem solving? I have generally found that there are three primary issues with the Organize bucket of analysis. All of these issues stem from problems that probably arise because of poor framing.

- The first issue occurs when a team organizes around the wrong things. Essentially, the issue tree either is not done in an MECE way or, more commonly, is not properly prioritized. The next issue is related, and it has to do with the allocation of resources in the team problem-solving process. The easiest (but not the most efficient) way to assign people to tasks is just to split things up evenly, without giving much thought to the workload and/or the impact of each area on the eventual end product. The final mistake that teams typically make in the Organize phase is failing to design a work plan that is centered on testing the hypotheses developed during the Frame phase. The scientific method requires the proving or disproving of hypotheses, which are essentially potential answers to the key question.

-

I cannot tell you how many times I heard the question, “What’s the story?” in the halls of McKinsey. The story line is essentially the outline for the final presentation at the end of the project. This is one of the secrets of efficient problem solving: you begin working on the final presentation story very early in the project—almost on day one. Right after the framing is finished and before systematic data gathering commences, the team should develop an initial story, brainstorming about both the actual story line and how to deliver it.

- The Operating Tactics for the Organize element of the TEAM FOCUS model are:

- Maintain objectivity as the hypotheses are tested during the project.

- Use frameworks as a starting point to identify issues for analysis.

- Explicitly list the types of analysis and related data that the team will and will not pursue (at least at that stage in the project life cycle).

- Revisit this list if the hypotheses are modified.

-

When it comes to the interview itself, one of the most common problems is that the interview is poorly conducted, and as a result is ineffective. The following three tips can help ensure that your team conducts meaningful interviews: Before the interview. The quality of the interview is likely to be determined well before the interview even takes place. The two key steps are (1) identify the right people to interview (who has unique knowledge about this topic, who can respond to the hypotheses, and who will be involved with implementation or subsequent efforts?) and (2) develop and share an interview guide (what are the three key topics to cover?). During the interview. A common mistake in interviews is to get carried away with trying to gather as much information as possible. A better strategy is to spend the time very carefully—for example, on insights and reactions to a hypothesis—and to build a positive relationship that would allow for comfortable follow-up conversations. After the interview. While a “thank-you” e-mail, letter, or card is certainly a good idea, the real recommendation I have for you is to document, document, and document. Within 24 hours, the consultant must document the key takeaways from the interview, including quotes and references to additional material. Also, share your interview notes with the other members of your team to keep them in the loop on your research. McKinsey utilizes a template form and provides training in interview notes documentation.

-

The starting point in strategic data gathering is to keep the context of the key question and the hypotheses in mind as you gather the data. If you start gathering a ton of data before you have really fleshed out your issue tree and internalized the key question, you will ultimately gather information that is perhaps only tangentially related to the core analysis.

-

My last suggestion is brief but critical: always document the source of your data on your charts. This is important for credibility (the idea is sufficiently supported), authenticity (it was not made up), and traceability (we can go back to the original source at a future point).

- The Operating Tactics for the Collect element of the TEAM FOCUS model are:

- Design ghost charts to exhibit the necessary data that are relevant to the overall story.

- Use primary research, and especially interview the client personnel; document interview guides ahead of time, and share the insights with the team in written form within 24 hours.

- Always cite the source of the data on each chart created.

- Go to the source! Finding a key contact with deep knowledge about your project’s topic is invaluable—especially in a situation like this, where you don’t have much prior experience or existing knowledge about your research area. I certainly spent a lot of time becoming familiar with issues and exploring dead ends before I found my key contact. In this project, I realized that people are generally happy to help you, and that it’s much easier to find an area expert and ask him or her questions than to try to wade through an abundance of new information yourself.

-

Two of the most important words within McKinsey are “so what?” This term has immediate connotations of testing the relevance of the data that have been gathered for a particular study. To operationalize this concept, it may be helpful to ask and answer one of three questions: “What is the impact of this insight on the project team’s tentative answer?” “Will this insight change the direction of our analysis?” and/or “Will implementation of this insight ultimately have a material impact on the client’s operations?” The answer to the questions will ultimately be the answer—or the “so what.”

-

The Collecting and Understanding processes are designed to work hand in hand during the team’s problem-solving journey. The team sketches out the story line, drafts ghost slides, gathers the data to fill in the charts, and then finalizes the insight statement on each chart. This is the most important part of the process. McKinsey typically inserts the insight at the top of each slide in the form of a sentence. This statement is extremely important to the process, as it makes explicit the reason why the chart exists and shares that reason with the rest of the team, and eventually with the client. A few tips for identifying and documenting the insight on each slide are (1) start early, (2) seek input, and (3) think in terms of impact for the client. In terms of timing, the first draft of the insight statement is actually prepared before any data are gathered. Finally, all insights should eventually be tied to some impact for the client.

- The Operating Tactics for the Understand element of the TEAM FOCUS model are:

- Ask “so what?” to sort through the analysis to find out what is ultimately important.

- Estimate the impact of the recommendations on the client’s operations.

-

Mike Yang offers the following bits of advice from his McKinsey days: “So what.” A story is not a story without the “so what”; it proves the importance of the insight and translates it into impact for clients. Implications for constituents. In addition to considering the constituents, you need to make sure that you validate the insights through private syndication. If you have a gut feeling that someone will not like the result, that person probably won’t. It’s better to prepare the various constituents for discussions and ask them for input ahead of time than to have unpleasant surprises in subsequent meetings. Document the key insight. Each chart should have a clear and meaningful point. If you can’t find that point, then this probably is not a good chart—remove it from the deck.

-

Data are necessary to form conclusions, and it is certainly necessary to back them up; however, just presenting a lot of information is useless. Furthermore, it’s generally not a good idea to just present a lot of information and let the audience draw its own conclusions.

-

The best way to ensure that you don’t leave your audience members hanging short of a solid conclusion and asking itself, “So what?” is to present clear solutions and relevant so-whats to them.

-

One of the most important operating assumptions for successful consulting engagements is to engage the client actively. Popular press stories of McKinsey being a firm that comes in with a fantastic strategy slide deck that cannot be implemented are unfounded. In fact, in every project at McKinsey, the team is charged with actively involving the client throughout the entire process and never completing a project without a detailed implementation plan and a specific understanding of the impact that the changes will have on the organization. The motivation for client involvement is quite clear and is related to the twofold mission statement that is documented in every one of McKinsey’s 90+ offices around the world: (1) help leaders make distinctive, lasting, and substantial improvements to the performance of their organizations and (2) provide our people with an outstanding place to work, with opportunities for growth that they can find nowhere else. The leaders of McKinsey’s client companies must take an active role during any McKinsey study. They provide perspectives and knowledge that are available nowhere else, they know the culture of the company, and they will ultimately be in charge of implementing the ideas and making positive changes in their respective organizations.

- Every final set of recommendations should have a governing point. This could be anchored in the general kind of change that the organization is pursuing (a change in strategic positioning, operational improvements, increased knowledge sharing, cost reductions, or some other area), the financial impact of the changes suggested, or some other organizing construct.

-

The next level down should capture a more specific set of recommendations (generally no more than three). The engagement’s findings will provide the rationale for these recommendations, and the proposed tactics will supply an execution plan. Each project may have its own particular set of recommendations, but the action steps will generally be supported by information about why and how.

- The “story” concept is common nomenclature within McKinsey—every project has a story (or overall “argument”), and it starts with the basic components that all stories share: situation, complication, and resolution. The team has to figure out the situation and complication (suggested in part by the engagement letter), then develop and test hypotheses to determine the resolution. More thinking up front in terms of strategic framing and organizing leads to more efficient data collection (as you are more focused and gather less irrelevant data).

-

Have you ever received or even written a message like this? “John Collins telephoned to say that he can’t make the meeting at 3:00. Hal Johnson says he doesn’t mind making it later, or even tomorrow, but not before 10:30, and Don Clifford’s secretary says that Clifford won’t return from Frankfurt until tomorrow, late. The Conference Room is booked tomorrow, but free Thursday. Thursday at 11:00 looks to be a good time. Is that OK for you?” If you present the main point first followed by supporting data, it would look like the message shown below. “Could we reschedule today’s meeting to Thursday at 11:00? This would be more convenient for Collins and Johnson, and would also permit Clifford to be present.” Can you see (and appreciate) the difference? You can imagine how significant it becomes with a 50-page slide deck that follows a three-month, $3 million project.

- There are three rules to keep in mind as you work out the structure of your ideas (also reprinted with the permission of Barbara Minto): Ideas at any level must be summaries of the ideas grouped below them Ideas in each grouping must be logically the same Ideas in each grouping must be in logical order.

-

Always focus on your audience. Learn as much as you can about your client, including but not limited to his or her education, tenure in the organization, title, preferences, and possible reactions to the recommendations (negative, neutral, or positive). Adjust accordingly! Speak the language of the client. Many clients actually have a disdain for “consulting speak” and prefer outsiders who learn to speak the language of the host company. This includes very careful control over early drafts of the story and recommendations, and perhaps not using the term hypothesis too much. (I have seen clients react negatively to this term, as they sometimes think you are forcing an early answer to their problem without adequate analysis.) Utilize a flexible presentation approach. Presentations and meetings have heterogeneous audiences with different backgrounds and preferences. It is important to balance slide decks and presentations to offer something for everyone. The beauty of the pyramid principle is that it allows you to do just that by providing a high-level message and loads of detail at different levels as well.

- The Operating Tactics for the Synthesize element of the TEAM FOCUS model are:

- Tell a story—use a very brief situation and complication followed by the resolution, which is the most important aspect of the project.

- Share the story with the client and the team ahead of time to obtain input and ensure buy-in.

- Keep the story simple, and focus on the original problem and specific recommendations for improvement; include the estimated impact on the organization.

- Have fun!