Playing to Win - A.G. Lafley

Note: While reading a book whenever I come across something interesting, I highlight it on my Kindle. Later I turn those highlights into a blogpost. It is not a complete summary of the book. These are my notes which I intend to go back to later. Let’s start!

- Strategy is about making specific choices to win in the marketplace.

-

Strategy is an integrated set of choices that uniquely positions the firm in its industry so as to create sustainable advantage and superior value relative to the competition.

-

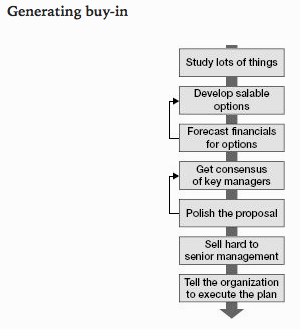

Instead of working to develop a winning strategy, many leaders tend to approach strategy in one of the following ineffective ways: They define strategy as a vision. Mission and vision statements are elements of strategy, but they aren’t enough. They offer no guide to productive action and no explicit road map to the desired future. They don’t include choices about what businesses to be in and not to be in. There’s no focus on sustainable competitive advantage or the building blocks of value creation. They define strategy as a plan. Plans and tactics are also elements of strategy, but they aren’t enough either. A detailed plan that specifies what the firm will do (and when) does not imply that the things it will do add up to sustainable competitive advantage. They deny that long-term (or even medium-term) strategy is possible. The world is changing so quickly, some leaders argue, that it’s impossible to think about strategy in advance and that, instead, a firm should respond to new threats and opportunities as they emerge. Emergent strategy has become the battle cry of many technology firms and start-ups, which do indeed face a rapidly changing marketplace. Unfortunately, such an approach places a company in a reactive mode, making it easy prey for more-strategic rivals. Not only is strategy possible in times of tumultuous change, but it can be a competitive advantage and a source of significant value creation. Is Apple disinclined to think about strategy? Is Google? Is Microsoft? They define strategy as the optimization of the status quo. Many leaders try to optimize what they are already doing in their current business. This can create efficiency and drive some value. But it isn’t strategy. The optimization of current practices does not address the very real possibility that the firm could be exhausting its assets and resources by optimizing the wrong activities, while more-strategic competitors pass it by. Think of legacy airlines optimizing their spoke-and-hub models while Southwest Airlines created a transformative new point-to-point business model. Optimization has a place in business, but it isn’t strategy. They define strategy as following best practices. Every industry has tools and practices that become widespread and generic. Some organizations define strategy as benchmarking against competition and then doing the same set of activities but more effectively. Sameness isn’t strategy. It is a recipe for mediocrity.

-

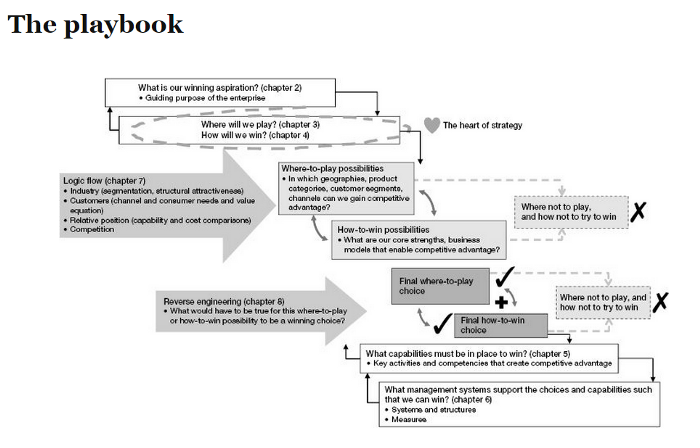

Winning should be at the heart of any strategy. In our terms, a strategy is a coordinated and integrated set of five choices: a winning aspiration, where to play, how to win, core capabilities, and management systems.

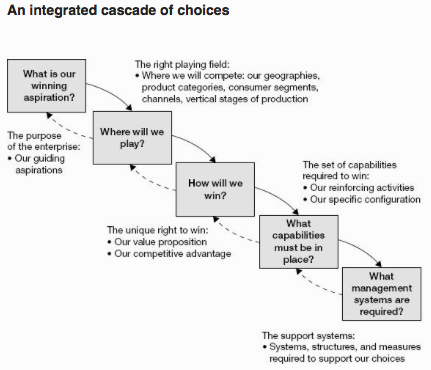

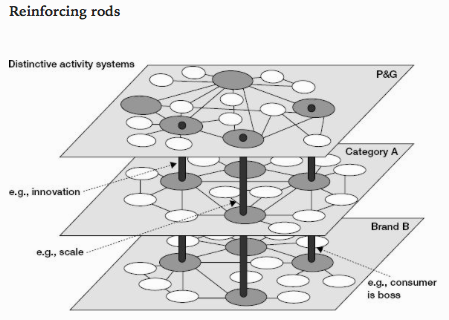

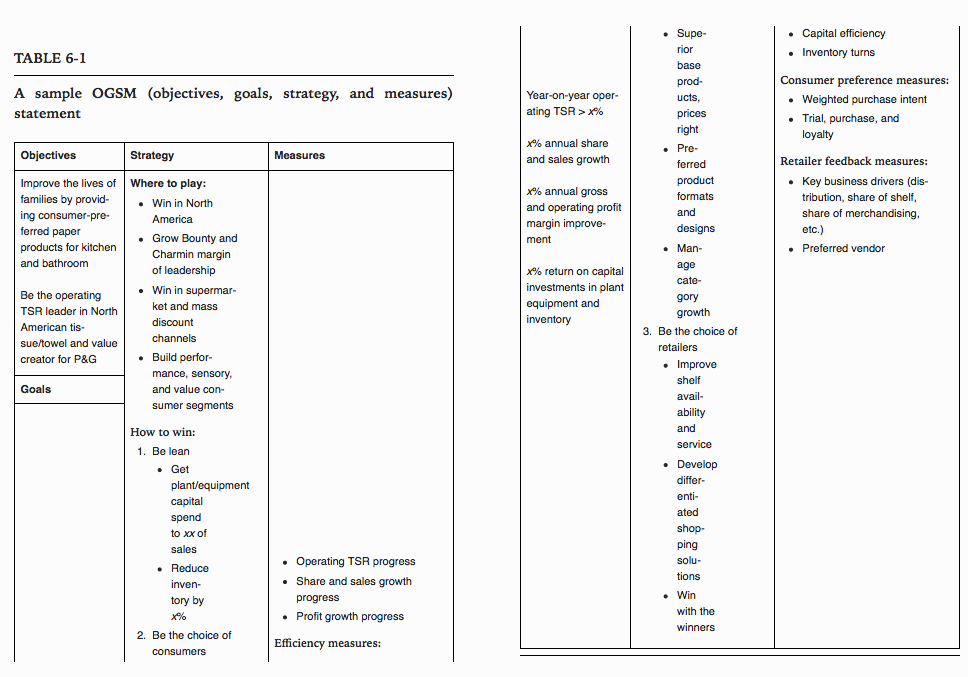

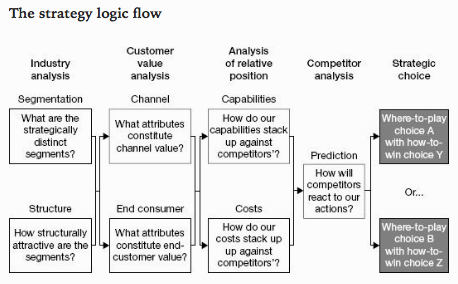

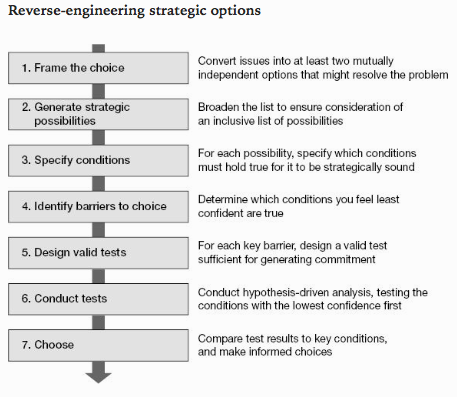

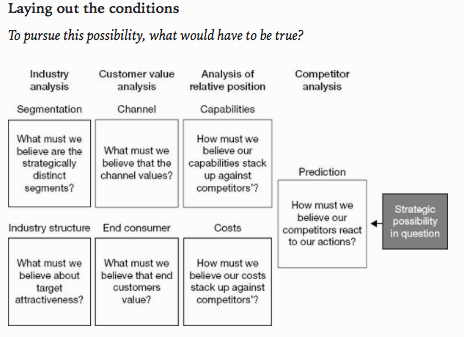

- Strategy can seem mystical and mysterious. It isn’t. It is easily defined. It is a set of choices about winning. Again, it is an integrated set of choices that uniquely positions the firm in its industry so as to create sustainable advantage and superior value relative to the competition. Specifically, strategy is the answer to these five interrelated questions: What is your winning aspiration? The purpose of your enterprise, its motivating aspiration. Where will you play? A playing field where you can achieve that aspiration. How will you win? The way you will win on the chosen playing field. What capabilities must be in place? The set and configuration of capabilities required to win in the chosen way. What management systems are required? The systems and measures that enable the capabilities and support the choices. These choices and the relationship between them can be understood as a reinforcing cascade, with the choices at the top of the cascade setting the context for the choices below, and choices at the bottom influencing and refining the choices above.

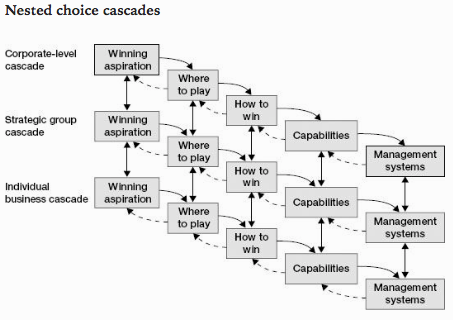

- The nested cascades mean that choices happen at every level of the organization. Consider a company that designs, manufactures, and sells yoga apparel. It aspires to create fierce brand advocates, to make a difference in the world, and to make money doing it. It chooses to play in its own retail stores, with athletic wear for women. It decides to win on the basis of performance and style. It creates yoga gear that is both technically superior (in terms of fit, flex, wear, moisture wicking, etc.) and utterly cool. It turns over its stock frequently to create a feeling of exclusivity and scarcity. It draws customers into the store with staff members who have deep expertise. It defines a number of capabilities essential to winning, like product and store design, customer service, and supply-chain expertise. It creates sourcing and design processes, training systems for staff, and logistics management systems. All of these choices are made at the top of the organization. But these choices beget more choices in the rest of the organization.

- Should the product team stay only in clothing or expand to accessories? Should it play in menswear as well? Should the retail operations group stay in bricks and mortar or expand online? Within retail, should there be one store model or several to adapt to different geographies and customer segments? At the store level, how should the staff person serve the customer, here and now, in order to win? Each level in the organization has its own strategic choice cascade.

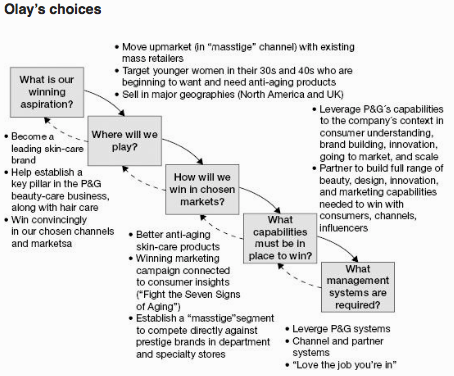

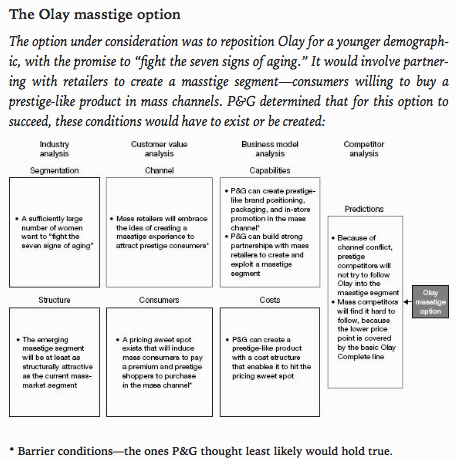

- The first question—what is our winning aspiration?—sets the frame for all the other choices. A company must seek to win in a particular place and in a particular way. If it doesn’t seek to win, it is wasting the time of its people and the investments of its capital providers. But to be most helpful, the abstract concept of winning should be translated into defined aspirations. Aspirations are statements about the ideal future. At a later stage in the process, a company ties to those aspirations some specific benchmarks that measure progress toward them. At Olay, the winning aspirations were defined as market share leadership in North America, $1 billion in sales, and a global share that put the brand among the market leaders. A revitalized and transformed Olay was expected to establish skin care as a strong pillar for beauty along with hair care. Establishing and maintaining leadership of a new masstige segment, positioned between mass and prestige, was a third aspiration. This set of aspirations served as a starting point to define where to play and how to win, enabling the Olay team to see the larger purpose in what it was doing. Clarity about the winning aspirations meant that actions at the brand, category, sector, and company level were directed at delivering against that ideal.

-

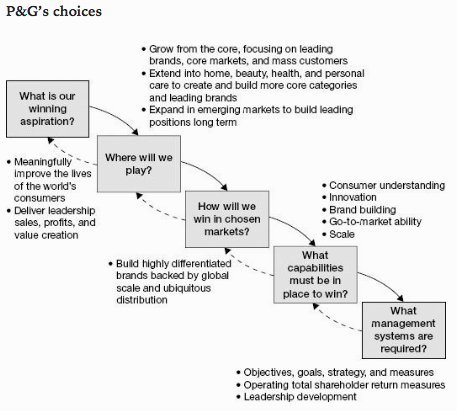

At the overall company level, winning was defined as delivering the most valuable, value-creating brands in every category and industry in which P&G chose to compete (in other words, market leadership in all of P&G’s categories). The aspiration was to create sustainable competitive advantage, superior value, and superior financial returns. P&G’s statement of purpose, at the time, read as follows: “We will provide products and services of superior quality and value that improve the lives of the world’s consumers. As a result, consumers will reward us with leadership sales, profit and value creation, allowing our people, our shareholders, and the communities in which we live and work to prosper.” Improving consumers’ lives to drive leadership sales, profit, and value creation was the company’s most important aspiration. It drove all subsequent choices.

- Aspirations can be refined and revised over time. However, aspirations shouldn’t change day to day; they exist to consistently align activities within the firm, so should be designed to last for some time. A definition of winning provides a context for the rest of the strategic choices; in all cases, choices should fit within and support the firm’s aspirations.

-

A definition of winning provides a context for the rest of the strategic choices.

- The next two questions are where to play and how to win. These two choices, which are tightly bound up with one another, form the very heart of strategy and are the two most critical questions in strategy formulation. The winning aspiration broadly defines the scope of the firm’s activities; where to play and how to win define the specific activities of the organization—what the firm will do, and where and how it will do this, to achieve its aspirations. Where to play represents the set of choices that narrow the competitive field. The questions to be asked focus on where the company will compete—in which markets, with which customers and consumers, in which channels, in which product categories, and at which vertical stage or stages of the industry in question. This set of questions is vital; no company can be all things to all people and still win, so it is important to understand which where-to-play choices will best enable the company to win. A firm can be narrow or broad. It can compete in any number of demographic segments (men ages eighteen to twenty-four, midlife urbanites, working moms) and geographies (local, national, international, developed world, economically fast-advancing countries like Brazil and China). It can compete in myriad services, product lines, and categories. It can participate in different channels (direct to consumer, online, mass merchandise, grocery, department store). It can participate in the upstream part of its industry, downstream, or be vertically integrated. These choices, when taken together, capture the strategic playing field for the firm.

- Olay made two strategically decisive where-to-play choices: to create, with retail partners, a new masstige segment in mass discount stores, drugstores, and grocery stores to compete with prestige brands and to develop a new and growing point-of-entry consumer segment for anti-aging skin-care products. Many other where-to-play options were considered (like moving into prestige channels and selling through department and specialty stores), but to win, Olay’s choices on where to play needed to make sense in light of P&G’s company-level where-to-play choices and capabilities. P&G tends to do well when the consumer is highly involved with the product category and cares a good deal about product experience and performance. It excels with brands that promise real improvement when the consumer puts in effort on a regular basis, as part of a well-defined regimen. P&G also does well with brands that can be sold through its best customers, retailers with which it has strong relationships and with which it can create significant shared value. So, the Olay team decided where to play with the P&G choices and capabilities in mind. Corporately, when it came to where to play, the company needed to define which regions, categories, channels, and consumers would give P&G a sustainable competitive advantage. The idea was to play in those areas where P&G’s capabilities would be decisive and to avoid areas where they were not. The concept that helped P&G leaders sort one area from the other and to define the strategic playing field clearly was the idea of core. We wanted to play where P&G’s core strengths would enable it to win. We asked which brands truly were core brands, identifying a set of brands that were clear industry or category leaders and devoting resources to them disproportionately. We asked what P&G’s core geographies were. With ten countries representing 85 percent of profits, P&G had to focus on winning in those countries. We asked where consumers expected P&G brands and products to be sold, that is, mass merchandisers and discounters, drugstores, and grocery stores. Core became a theme in innovation as well. P&G scientists determined the core technologies that were important across the businesses and focused on those technologies above all others. We wanted to shift from a pure invention mind-set to one of strategic innovation; the goal was innovation that drove the core. Core consumers were a theme too; we pushed businesses to focus on the consumer who matters most, targeting the most attractive consumer segments. Core was the first and most fundamental where-to-play choice—to focus on core brands, geographies, channels, technologies, and consumers as a platform for growth. The second where-to-play choice was to extend P&G’s core into demographically advantaged and structurally more attractive categories. For example, the core was to move from fabric into home care, from hair care into hair color and styling, and more broadly into beauty, health, and personal care. The third where-to-play choice—to expand into emerging markets—was driven by demographics and economics. The majority of babies would be born, and households formed, in emerging markets. Economic growth in these markets will be as much as four times as high as in the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) developed markets. The question was how many markets P&G could take on and in what priority order. The company started with China, Mexico, and Russia, building capability and reach over time to include Brazil, India, and others. As Chip Bergh, former group president for global grooming and now CEO of Levi Strauss & Co., notes, “In 2000, about 20 percent of P&G’s total sales were in emerging markets compared to Unilever and Colgate, which were already up near 40 percent. We were a company of premium-priced products, always going after product superiority. We tended to play, as a company, in the premium tiers in almost all categories.”6 To compete in the developing world, Bergh says, a change in orientation was required: “We needed to begin broadening our portfolio and developing competitive propositions, including cost structures that would allow us to reach deeper into these emerging markets. There are a billion consumers in India, and we were reaching the top 10 percent of them.”

- There were three critical where-to-play choices for P&G at the corporate level:

- Grow in and from the core businesses, focusing on core consumer segments, channels, customers, geographies, brands, and product technologies.

- Extend leadership in laundry and home care, and build to market leadership in the more demographically advantaged and structurally attractive beauty and personal-care categories.

- Expand to leadership in demographically advantaged emerging markets, prioritizing markets by their strategic importance to P&G.

- Where to play selects the playing field; how to win defines the choices for winning on that field. It is the recipe for success in the chosen segments, categories, channels, geographies, and so on. The how-to-win choice is intimately tied to the where-to-play choice. Remember, it is not how to win generally, but how to win within the chosen where-to-play domains. The where-to-play and how-to-win choices should flow from and reinforce one another. Think of the contrast between two kinds of restaurant empires—say, Olive Garden versus Mario Batali. Both specialize in Italian food, and both are successful across multiple locations. But they represent very different where-to-play choices. Olive Garden is a midpriced, casual dining chain with considerable scale—more than seven hundred restaurants around the world. As a result, its how-to-win choices relate to meeting the needs of average diners and focus on achieving reliable, consistent outcomes when hiring thousands of employees to reproduce millions of meals that will suit a wide array of tastes. Mario Batali, on the other hand, competes at the very high end of the fine-dining space and does so in just a few places—New York, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and Singapore. He wins by designing innovative and exciting recipes; sourcing the very best of ingredients; delivering superlative, customized service; and sharing his cachet with his foodie patrons—cachet generated by Batali’s Food Network celebrity and friendships with the likes of actress Gwyneth Paltrow.

- In great strategies, the where-to-play and how-to-win choices fit together to make the company stronger. Given their where-to-play choices, it would not make sense for Olive Garden to try to win by increasing the celebrity status of its head chef, nor for Batali to even contemplate making each location look just like the others. But if Batali wanted to seriously expand to a lower-priced, casual dining range, as Wolfgang Puck has done, Batali would need to expand his how-to-win choices to fit the new, broader where-to-play choice. If he failed to do so, he would likely fail to engage the new market. Where-to-play and how-to-win choices must be considered together, because no how-to-win is perfect, or even appropriate, for all where-to-play choices.

- To determine how to win, an organization must decide what will enable it to create unique value and sustainably deliver that value to customers in a way that is distinct from the firm’s competitors. Michael Porter called it competitive advantage—the specific way a firm utilizes its advantages to create superior value for a consumer or a customer and in turn, superior returns for the firm.

-

For Olay, the how-to-win choices were to formulate genuinely better skin-care products that could actually fight the signs of aging, to create a powerful marketing campaign that clearly articulated the brand promise (“Fight the Seven Signs of Aging”), and to establish a masstige channel, working with mass retailers to compete directly with prestige brands. The masstige choice, which was a decision to win in the channels P&G knew best, required significant changes in product formulation, package design, branding, and pricing to reframe the value proposition for retailers and consumers. Corporately, P&G chose to compete from the core; to extend into home, beauty, health, and personal care; and to expand into emerging markets. The how-to-win choices needed to work optimally with these where-to-play choices. To be successful, how-to-win choices should be suited to the specific context of the firm in question and highly difficult for competitors to copy. P&G’s competitive advantages are its ability to understand its core consumers and to create differentiated brands. It wins by relentlessly building its brands and through innovative product technology. It leverages global scale and strong partnerships with suppliers and channel customers to deliver strong retail distribution and consumer value in its chosen markets. If P&G played to its strengths and invested in them, it could sustain competitive advantage through a unique go-to-market model. P&G’s where-to-play and how-to-win-choices aren’t appropriate for every context. The key to making the right choices for your business is that they must be doable and decisive for you. If you are a small entrepreneurial firm facing much larger competitors, making a how-to-win choice on the basis of scale would not make much sense. But simply because you are small doesn’t mean winning through scale is impossible. Don’t dismiss the possibility that you can change the context to fit your choices. Bob Young, cofounder of Red Hat, Inc., knew precisely where he wanted his company to play: he wanted to serve corporate customers with open-source enterprise software. In his view, the how-to-win in that context required scale—Young saw that corporate customers were much more likely to buy from a market leader, especially a dominant market leader. At the time, the Linux market was highly fragmented, with no such clear leader. Young had to change the game—by literally giving his software away via free download—to achieve dominant market share and become credible to corporate information technology (IT) departments. In that case, Young decided where to play and how to win, and then built the rest of his strategy (earning revenue from service rather than software sales) around these two choices. The result was a billion-dollar company with a thriving enterprise business. The myriad ways to win, and possibilities for thinking through them, will be explored in greater depth in chapter 4. There, we begin with the story of a set of technologies that posed a particularly challenging how-to-win choice for P&G.

-

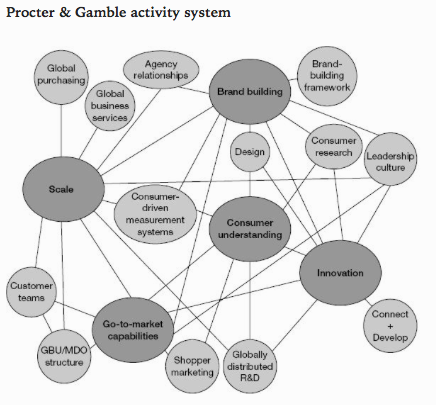

Two questions flow from and support the heart of strategy: (1) what capabilities must be in place to win, and (2) what management systems are required to support the strategic choices? The first of these questions, the capabilities choice, relates to the range and quality of activities that will enable a company to win where it chooses to play. Capabilities are the map of activities and competencies that critically underpin specific where-to-play and how-to-win choices. The Olay team had to invest in building and creating its capabilities on a number of fronts: clearly, innovation would be vital—and not just product innovation—but packaging, distribution, marketing, and even business model innovation would play a role. The team would need to leverage its existing consumer insights to truly understand a different segment. It would have to build the brand, advertise, and merchandise with mass retailers in new ways. Olay and P&G skin care couldn’t go it alone. So, they partnered with product ingredient innovators (Cellderma), designers (IDEO and others), advertising and PR agencies (Saatchi & Saatchi), and key influencers (like beauty magazine editors and dermatologists, for credible product performance endorsements). This networked alliance of internal and external capabilities created a unique and powerful activity system. It required deepening existing capabilities and building new ones. At P&G, a company with more than 125,000 employees worldwide, the range of capabilities is broad and diverse.

- A few capabilities are absolutely fundamental to winning in the places and manner that it has chosen:

- Deep consumer understanding. This is the ability to truly know shoppers and end users. The goal is to uncover the unarticulated needs of consumers, to know consumers better than any competitors do, and to see opportunities before they are obvious to others.

- Innovation. Innovation is P&G’s lifeblood. P&G seeks to translate deep understanding of consumer needs into new and continuously improved products. Innovation efforts may be applied to the product, to the packaging, to the way P&G serves its consumers and works with its trade customers, or even to its business models, core capabilities, and management systems.

- Brand building. Branding has long been one of P&G’s strongest capabilities. By better defining and distilling a brand-building heuristic, P&G can train and develop brand leaders and marketers in this discipline effectively and efficiently.

- Go-to-market ability. relationships. P&G thrives on reaching its customers and consumers at the right time, in the right place, in the right way. By investing in unique partnerships with retailers, P&G can create new and breakthrough go-to-market strategies that allow it to deliver more value to consumers in the store and to retailers throughout the supply chain.

- Global scale. P&G is a global, multicategory company. Rather than operate in distinct silos, its categories can increase the power of the whole by hiring together, learning together, buying together, researching and testing together, and going to market together. In the 1990s, P&G amalgamated a whole suite of internal support services, like employee services and IT, under one umbrella—global business services (GBS)—to allow it to capture the scale benefits of those functions globally.

-

These five core capabilities support and reinforce one another and, taken together, set P&G apart. In isolation, each capability is strong, but insufficient to generate true competitive advantage over the long term. Rather, the way all of them work together and reinforce each other is what generates enduring advantage. A great new idea coming out of P&G labs can be effectively branded and shelved around the world in the best retail outlets in each market. That combination is hard for competitors to match.

-

The final strategic choice in the cascade focuses on management systems. These are the systems that foster, support, and measure the strategy. To be truly effective, they must be purposefully designed to support the choices and capabilities. The types of systems and measures will vary from choice to choice, capability to capability, and company to company. In general, though, the systems need to ensure that choices are communicated to the whole company, employees are trained to deliver on choices and leverage capabilities, plans are made to invest in and sustain capabilities over time, and the efficacy of the choices and progress toward aspirations are measured. Beneath Olay’s choices and capabilities, the team built supporting systems and measures that included a “love the job you’re in” human resources strategy (to encourage personal development and deepen the talent pool in the beauty sector) and detailed tracking systems to measure consumer responses to brand, package, product lines, and every other element of the marketing mix. Olay organized around innovation, creating a structure wherein one team was working on the strategy and rollout of current products while another was designing the next generation. It developed technical marketers, individuals with expertise in R&D as well as marketing, who could speak credibly to dermatologists and beauty editors. It created systems to partner with leading in-store marketing and design firms, to create Olay displays that were eye-catching and inviting to shop. It also leveraged P&G systems like global purchasing, the global market development organization (MDO), and GBS so that individuals on the skin-care and Olay teams were freed up to focus where they added the most value. At the corporate level, management systems included strategy dialogues, innovation-program reviews, brand-equity reviews, budget and operating plan discussions, and talent assessment development reviews. From the year 2000 on, every one of these management systems was changed significantly so that it became more effective. All of these systems were tightly integrated, mutually reinforcing, and crucial to winning.

- It also leveraged P&G systems like global purchasing, the global market development organization (MDO), and GBS so that individuals on the skin-care and Olay teams were freed up to focus where they added the most value. At the corporate level, management systems included strategy dialogues, innovation-program reviews, brand-equity reviews, budget and operating plan discussions, and talent assessment development reviews. From the year 2000 on, every one of these management systems was changed significantly so that it became more effective. All of these systems were tightly integrated, mutually reinforcing, and crucial to winning.

- CHOICE CASCADE DOS AND DON’TS

- Do remember that strategy is about winning choices. It is a coordinated and integrated set of five very specific choices. As you define your strategy, choose what you will do and what you will not do.

- Do make your way through all five choices. Don’t stop after defining winning, after choosing where to play and how to win, or even after assessing your capabilities. All five questions must be answered if you are to create a viable, actionable, and sustainable strategy.

- Do think of strategy as an iterative process; as you uncover insights at one stage in the cascade, you may well need to revisit choices elsewhere in the cascade.

- Do understand that strategy happens at multiple levels in the organization. An organization can be thought of as a set of nested cascades. Keep the other cascades in mind while working on yours.

- Do remember that there is no one perfect strategy; find the distinctive choices that work for you. It isn’t entirely easy to make your way through the full choice cascade.

- Aspirations are the guiding purpose of an enterprise.

-

Winning is what matters—and it is the ultimate criterion of a successful strategy. Once the aspiration to win is set, the rest of the strategic questions relate directly to finding ways to deliver the win.

-

Saturn was GM’s answer to the Japanese imports that threatened to dominate the small-car market; it was a defensive strategy, a way of playing in the small-car segment, designed to protect what remained of the ground GM was losing.

-

The folks running Saturn aspired to participate in the US small-car segment with younger buyers. By contrast, Toyota, Honda, and Nissan all aspired to win in that segment. Guess what happened? Toyota, Honda, and Nissan all aimed for the top, making the hard strategic choices and substantial investments required to win. GM, through Saturn, aimed to play and invested to that much lower standard. Initially Saturn did OK as a brand. But it needed substantial resources to keep up against Toyota, Honda, and Nissan, all of which were investing at breakneck speed. GM couldn’t and wouldn’t keep up. Saturn died, not because it made bad cars, but because its aspirations were simply too modest to keep it alive. The aspirations did not spur winning where-to-play and how-to-win choices, capabilities, and management systems.

- To be fair, GM had myriad challenges that made playing to win a daunting prospect—troubling union relations, oppressive legacy health-care and pension costs, and difficult dealer regulations. However, playing to play, rather than seeking to play to win, perpetuated the overall corporate problems rather than overcoming them. Contrast the approach at GM to the approach at P&G, where the company plays to win whenever it chooses to play. And the approach holds even in the unlikeliest of places. Playing to win is reasonably straightforward to contemplate in a consumer market.

- The desire to win spurs a helpfully competitive mind-set, a desire to do better whenever possible. For this reason, GBS competes for its internal customers. Passerini explains: “We don’t mandate new services; we offer them [to businesses and functions] at a cost. If the business units like them, they will buy them. If they don’t like them, they will pass.” This open market provides important feedback and keeps GBS thinking about how to win with its internal customers and create new value. So much so that Passerini famously stood at a global leadership team meeting and promised: “Give me anything I can turn into a service, and I’ll save you seventeen cents on the dollar.” It was a provocative offer, and one that set the tone for his team. Good enough wasn’t an option. Providing services wasn’t the strategy. Providing better services at higher quality and lower costs—while serving as an innovation engine for the company—was the strategy. It was a strategy aimed at winning.

- Companies in the grips of marketing myopia are blinded by the products they make and are unable to see the larger purpose or true market dynamics. These companies spend billions of dollars making their new generation of products just slightly better than their old generation of products. They use entirely internal measures of progress and success—patents, technical achievements, and the like—without stepping back to consider the needs of consumers and the changing marketplace or asking what business they are really in, which consumer need they answer, and how best to meet that need. The biggest danger of having a product lens is that it focuses you on the wrong things—on materials, engineering, and chemistry. It takes you away from the consumer. Winning aspirations should be crafted with the consumer explicitly in mind. The most powerful aspirations will always have the consumer, rather than the product, at the heart of them. In P&G’s home-care business, for instance, the aspiration is not to have the most powerful cleanser or most effective bleach. It is to reinvent cleaning experiences, taking the hard work out of household chores. It is an aspiration that leads to market-shifting products like Swiffer, the Mr. Clean Magic Eraser, and Febreze.

- P&G had a run of six years of strong revenue and double-digit earnings per share growth, and Reckitt-Benckiser was outperforming even that. It wasn’t so much about Reckitt-Benckiser itself as it was about getting the general managers to question their assumptions and their current judgments. The push was to ask, “Who really is your best competitor? More importantly, what are they doing strategically and operationally that is better than you? Where and how do they outperform you? What could you learn from them and do differently?” Looking at the best competitor, no matter which company it might be, provides helpful insights into the multiple ways to win.

- Unless winning is the ultimate aspiration, a firm is unlikely to invest the right resources in sufficient amounts to create sustainable advantage. But aspirations alone are not enough. Leaf through a corporate annual report, and you will almost certainly find an aspirational vision or mission statement. Yet, with most corporations, it is very difficult to see how the mission statement translates into real strategy and ultimately strategic action. Too many top managers believe their strategy job is largely done when they share their aspiration with employees. Unfortunately, nothing happens after that. Without explicit where-to-play and how-to-win choices connected to the aspiration, a vision is frustrating and ultimately unfulfilling for employees. The company needs where and how choices in order to act. Without them, it can’t win.

- WINNING ASPIRATION DOS AND DON’TS

- Do play to win, rather than simply to compete. Define winning in your context, painting a picture of a brilliant, successful future for the organization.

- Do craft aspirations that will be meaningful and powerful to your employees and to your consumers; it isn’t about finding the perfect language or the consensus view, but is about connecting to a deeper idea of what the organization exists to do.

- Do start with consumers, rather than products, when thinking about what it means to win.

- Do set winning aspirations (and make the other four choices) for internal functions and outward-facing brands and business lines. Ask, what is winning for this function? Who are its customers, and what does it mean to win with them?

- Do think about winning relative to competition. Think about your traditional competitors, and look for unexpected “best” competitors too.

- Don’t stop here. Aspirations aren’t strategy; they are merely the first box in the choice cascade.

-

I wanted my team to understand that strategy is disciplined thinking that requires tough choices and is all about winning. Grow or grow faster is not a strategy. Build market share is not a strategy. Ten percent or greater earnings-per-share growth is not a strategy. Beat XYZ competitor is not a strategy. A strategy is a coordinated and integrated set of where-to-play, how-to-win, core capability, and management system choices that uniquely meet a consumer’s needs, thereby creating competitive advantage and superior value for a business. Strategy is a way to win—and nothing less.

- Deep consumer understanding is at the heart of the strategy discussion. To be effective, strategy must be rooted in a desire to meet user needs in a way that creates value for both the company and the consumer. In considering where to play among consumer segments, the Bounty team asked some critical questions: Who is the consumer? What is the job to be done? Why do consumers choose what they do, relative to the job to be done? Bounty had tremendous awareness and brand equity in the North American marketplace. “It had by far the best equity in its category—one of the strongest brand equities in the company,” says Pierce. “If you asked, virtually 100 percent of people would say Bounty is a great brand and a really good product. Then some would go off and buy something else. What’s wrong with this picture?” Pierce and his team set out to truly understand consumer needs, habits, and practices as they relate to paper towels. In watching and talking to consumers, they found that there were three distinct types of paper towel users. The first group cared about both strength and absorbency. For this group, Bounty was a perfect fit—a great combination of the two attributes they cared most about. The team found that among these consumers, Bounty was already the clear winner. Here, “Bounty didn’t have a forty share,” Pierce says. “It had an eighty share.” But many consumers didn’t fit into the strength-and-absorbency category; those consumers fell squarely into the remaining two segments. The second segment consisted of consumers who wanted a paper towel with a cloth-like feel. They didn’t care much about strength or absorbency, certainly much less than the core Bounty group did. Rather, this group of customers cared about how soft the paper towel felt in their hand. The final segment had price as their top priority, though not as their sole concern, says Pierce: “The need of those consumers was also on strength. It wasn’t at all on absorbency, because they had a compensating behavior to address the absorbency shortfalls of lower-priced paper-towel products: they would simply use more sheets.” These consumers were happy to use more sheets of a lower-priced paper towel, when needed, rather than spend more money for a premium brand that enabled the use of fewer sheets each time. It was a trade-off that made good sense to them. Bounty had captured most of the first consumer segment, but had made few inroads with the other two groups. Pierce wanted to play in all three segments to achieve more scale and enhance profitability. Going forward, Bounty would become not one but three distinct products—each one designed to target a specific consumer segment. Traditional Bounty would remain unchanged and serve the first segment, which already loved the brand. A new product called Bounty Extra Soft would target the consumers who craved a soft, cloth-like feel. And then there was the final segment—the strength-and-price segment. These consumers presented something of a challenge. Most of the lower-priced paper towels on the market were of poor quality, and the Bounty team didn’t want to devalue the core brand by associating it with a subpar product. “Those products fail miserably on strength,” Pierce notes. “They shred, they tear. They disintegrate in the face of a spill. Then, you not only have to deal with the spill, but you also have the mess of the towel residue to deal with.” To have the Bounty name—even at a value price point—a product would have to live up to the equity of the Bounty brand. The new offering for the strength-and-price segment was designed not as a stripped-down version of Bounty, but as a new product with specific consumer needs in mind. Bounty Basic was considerably stronger than any other value brand and priced at about 75 percent of the cost of regular Bounty. Shelved away from traditional Bounty, with the other lower-priced brands, it spoke directly to the third segment of consumers. While there was some concern that existing Bounty consumers might trade down to Bounty Basic, the relative attributes of the three products fit each segment’s needs so perfectly that little shifting actually occurred. Pierce notes, “The old Bounty was one product that existed for decades. The modern-day Bounty is now three products that were designed against very clear consumer understanding and consumer segmentation. They’re all very different from each other on a product performance standpoint, and each is designed to meet the needs of its users.” Ultimately, the family-care team chose not to play in the truly commodity portion of the market; while Bounty Basic is a value offering, it is priced at a premium to private-label brands and offers a clear strength advantage. By staying in the noncommodity space, in terms of both product assortment and price point, P&G can target its core consumers through its most valued core retailers (its best and biggest customers), levering core advantages in innovation and brand building. Pierce and his team made where-to-play choices on geography (North America), consumers (three segments in the top half of the market), products (paper towels, branded basic and premium), channels (grocery stores, mass discounters, drugstores, and membership club stores like Costco), and stages of production (R&D and production of the paper towel itself, but not growing, harvesting, or pulping the trees). Making these clear where-to-play choices, for Bounty and the family-care category, spurred innovation and helped powerful brands grow even stronger. As a result, P&G family care consistently delivered business growth and value creation at industry-leading levels.

- The choice of where to play defines the playing field for the company (or brand, or category, etc.). It is a question of what business you are really in. It is a choice about where to compete and where not to compete. Understanding this choice is crucial, because the playing field you choose is also the place where you will need to find ways to win. Where-to-play choices occur across a number of domains, notably these:

- Geography. In what countries or regions will you seek to compete?

- Product type. What kinds of products and services will you offer?

- Consumer segment. What groups of consumers will you target? In which price tier? Meeting which consumer needs?

- Distribution channel. How will you reach your customers? What channels will you use? Vertical stage of production.

- In what stages of production will you engage? Where along the value chain? How broadly or narrowly?

- At P&G, where to play choices start with the consumer: Who is she? What does the consumer want and need? To win with mom, P&G invests heavily in truly understanding her—through observation, through home visits, through a significant investment in uncovering unmet and unexpressed needs. Only through a concerted effort to understand the consumer, her needs, and the way in which P&G can best serve those needs is it possible to effectively determine where to play—which businesses to enter or leave, which products to sell, which markets to prioritize, and so on. As current CEO Bob McDonald explains, “We don’t give lip service to consumer understanding. We dig deep. We immerse ourselves in people’s day-to-day lives. We work hard to find the tensions that we can help resolve. From those tensions come insights that lead to big ideas.”2 Those big ideas can be the basis of a powerful where-to-play choice. The distribution channel choice also tends to loom large for P&G, because of the dominant size and market power of the retailers in question. Tesco has more than 30 percent of the UK market.3 Walmart serves some 200 million Americans every week.4 Other players, like Loblaw in Canada or Carrefour in Europe, have substantial regional presence. For this reason, channel is a particularly crucial where-to-play consideration for the company. Of course, for some industries, there is no real channel consideration (e.g., in service industries that deal directly with the end consumer). Again, context matters—and each company must assess the weight of the different where-to-play choices for itself. One final consideration for where to play is the competitive set. Just as it does when it defines winning aspirations, a company should make its where-to-play choices with the competition firmly in mind. Choosing a playing field identical to a strong competitor’s can be a less attractive proposition than tacking away to compete in a different way, for different customers, or in different product lines. But strategy isn’t simply a matter of finding a distinctive path. A company may choose to play in a crowded field or in one with a dominant competitor if the company can bring new and distinctive value. In such a case, winning may mean targeting the lead competitor right away or going after weaker competitors first. So it was with Tide. When Liquid Tide was introduced in 1984, P&G was entering the liquid-detergent category against a strong, established competitor. Even with strong brand equity from its powdered detergent, this wouldn’t be an easy win. Wisk, Unilever’s market-leading liquid detergent, was a powerful, established brand with loyal customers. For the first two or three years, Wisk did not give up a share point against Liquid Tide. In Liquid Tide’s first year, Wisk actually gained share. Clearly, Wisk users weren’t moving to Tide. But P&G didn’t need to steal Wisk users to win in the category, at least not right away. The high-profile launch of Liquid Tide helped expand the overall liquid-detergent category, and P&G picked up the lion’s share of the expansion. Liquid Tide created new consumers for liquid detergent, and none of them had a loyalty to Wisk. As the category grew, Tide could begin to take share from smaller players, like Dynamo, which couldn’t compete with P&G’s R&D, scale, and brand-building expertise. Only then, having built critical mass, would Liquid Tide need to go after Wisk directly. At that point, the battle was all but won. For Liquid Tide, it wasn’t a matter of avoiding a playing field that held a fierce competitor. It was about expanding the playing field to make room for the two competitors and creating time to gain momentum. In the end, Liquid Tide won and took the market lead decisively.

-

There is a lot to consider when crafting a winning where-to-play choice, from consumers to channels and customers; to competition; to local, regional, and global differences. In the face of that kind of complexity, your strategy can easily fall prey to oversimplification, resignation, even desperation. In particular, you should avoid three pitfalls when thinking about where to play. The first is to refuse to choose, attempting to play in every field all at once. The second is to attempt to buy your way out of an inherited and unattractive choice. The third is to accept a current choice as inevitable or unchangeable. Giving in to any one of these temptations leads to weak strategic choices and, often, to failure.

-

Focus is a crucial winning attribute. Attempting to be all things to all customers tends to result in underserving everyone. Even the strongest company or brand will be positioned to serve some customers better than others. If your customer segment is “everyone” or your geographic choice is “everywhere,” you haven’t truly come to grips with the need to choose. But, you may argue, don’t companies like Apple and Toyota choose to serve everyone? No, not really. While they do have very large customer bases, the companies don’t serve all parts of the world and all customer segments equally. As late as 2009, Apple derived just 2 percent of its revenue from China. That was a choice—about where and when to play. It was a choice based on resources, capabilities, and an understanding that even Apple can’t be everywhere at once.

-

Companies often attempt to move out of an unattractive game and into an attractive one through acquisition. Unfortunately, it rarely works. A company that is unable to strategize its way out of a current challenging game will not necessarily excel at a different one—not without a thoughtful approach to building a strategy in both industries. Most often, an acquisition adds complexity to an already scattered and fragmented strategy, making it even harder to win overall. Resource companies are particularly susceptible to this trap, as they often lust after the value-added producers in their industries. Whether in aluminum, newsprint, or coal, an acquirer is often seduced by the idea of access to the higher prices and faster growth rates of a downstream industry. Unfortunately, there are two big problems with this kind of acquisition. The first is price. It costs a great deal to buy into attractive industries—quite often, acquirers must pay more than the asset could ever be worth to them, which dooms the acquirer in the long run. Second, the strategy and capabilities required in the targeted industry are often very different from those in the current industry; it is seriously tough sledding to bridge the two approaches and have an advantage in both (in mining bauxite and processing aluminum, for instance). Such acquisitions tend to be both overly expensive and strategically challenging. Rather than attempting to acquire your way into a more attractive position, you can set a better goal for your company. The real goal should be to create an internal discipline of strategic thinking that enables a more thoughtful approach to the current game, regardless of industry, and connects to possible different futures and opportunities.

-

It can also be tempting to view a where-to-play choice as a given, as having been made for you. But a company always has a choice of where to play. To return to a favorite example, Apple wasn’t bound entirely by its first where-to-play choice—which was desktop computers. Though it eventually established a comfortable niche in that world, as the desktop of choice for creative industries, Apple chose to change its playing field to move into the portable communication and entertainment space with the iPod, iTunes, iPhone, and iPad. It is tempting to think that you have no choice in where to play, because it makes for a great excuse for mediocre performance. It is not easy to change playing fields, but it is doable and can make all the difference. Sometimes the change is subtle, like a shift in consumer focus within a current industry—as with Olay. Other times the change can be dramatic, like at Thomson Corporation. Twenty years ago, the company’s where-to-play choice was North American newspapers, North Sea oil, and European travel; today (as Thomson Reuters), it competes only in must-have, software-enhanced, subscription-based information delivered over the web. There is almost zero overlap between the old and new where-to-play choices for Thomson. The change didn’t happen overnight—it took twenty years of dedicated work—but it demonstrates that changing an existing where-to-play choice is doable.

-

Even well-established brands have multiple choices. We’ve already seen the Olay where-to-play choice and how it changed over time. Rather than attempting to deliver products to all women, in all age categories, at the lower end of the market, the Olay team chose to compete primarily on a narrower field—women aged thirty-five-plus who were newly concerned with the signs of aging. This was just one of many possible choices for the brand, an explicit narrowing and shifting of the previous where-to-play choice. Then there is one of P&G’s biggest brands: Tide. It gained strength by broadening its where-to-play choice. Once, the Tide team was focused almost entirely on the dirt you can actually see on clothes. As late as the 1980s, Tide had two forms—the traditional washing powder and the liquid version—both geared at getting the visible dirt out of your clothes (“Tide’s in, Dirt’s out”). P&G broadened its where-to-play choice for Tide by moving beyond visible dirt. Tide introduced product versions designed to address a whole range of cleaning needs—Tide with Bleach, Tide Plus a Touch of Downy, Tide Plus Febreze, Tide for Coldwater, Tide Unscented; then, P&G expanded the Tide offering from detergents to other laundry-related products—creating a line of stain-release products, most notably the highly successful Tide-to-Go instant stain remover. The goal was to build a product line that effectively addressed different loads, different consumers, even different family members. Tide expanded its distribution model as well. The team started to look at the distributors that offer a very limited number of brands, like drugstores, wholesale stores like Costco, dollar stores, and vending machines at self-service laundries and campgrounds. These channels tend to offer just one national brand and a private-label option. P&G pushed hard to have Tide chosen as the national brand in each case. As the leading brand in the category, it had a compelling case. The horizon has even expanded to Tide-branded dry cleaners. A broader definition of where to play served as the building block to extend the brand. Each new Tide product is built on the superior cleaning ability of Tide and its value-added benefits, reinforcing the core brand. In this way, Tide broadened to get stronger. Times had changed, and P&G had failed to change with them. There were fewer hard surfaces in homes, as fiberglass (and porous marbles and other stones) replaced porcelain. Competitors had introduced less abrasive cleansers that resonated with consumers; P&G had not. “It was clear we had to do something very, very different,” Bergh notes. “We realized that our products were no longer relevant for the consumer and that we had been out-innovated.” So Bergh challenged his team to think about where to play from an entirely new perspective that would be grounded in an understanding of the competitive landscape and of P&G’s core capabilities. “I took my leadership team off-site for two days,” he says. “The focus was to come up with a set of choices that would make a difference on the business. The rallying cry we had around the new choices, and around the new strategy, was to fundamentally change the game of cleaning at home and make cleaning less of a chore.” As ever, the starting point was consumer needs—like quick surface cleaning without muss and fuss, addressing a particular job and doing it better than current offerings. Bergh continues: “We asked, how do we leverage the company scale and size and technology expertise to fundamentally change cleaning at home? The key breakthrough for us was to start putting together different technologies that P&G had, but our competitors didn’t. How do you marry chemistry, surfactant technology, and paper technology? All of that led, within two years, to the launch of Swiffer.” Swiffer proved to be a whole new where-to-play choice for the hard-surface cleaners business. It was a consumer-led blockbuster. BusinessWeek listed it as one of “20 Products That Shook the Stock Market.”6 Ten years later, Swiffer is now in 25 percent of US households. And as competition enters into the category it created, P&G is turning its attention to the next strategic frontier for Swiffer, asking what’s next.

-

It can be easy to dismiss new and different where-to-play choices as risky, as a poor fit with the current business, or as misaligned with core capabilities. And it is just as easy to write off an entire industry on the basis of the predominant where-to-play choices made by the competitors in that industry. But sometimes, you must dig a bit deeper—to examine unexpected where-to-play choices from all sides—to truly understand what is possible and how an industry can be won with a new place to play.

- Fine fragrances, however, were important to hang on to, for two strategic reasons. First, a fine-fragrance presence was an important component of a credible and competitive beauty business. P&G wanted to be a beauty leader, on the strength of hair care (Pantene, Head & Shoulders) and skin care (Olay). But to be truly credible with the industry and consumers as a beauty player, the company needed a position in cosmetics and fragrances as well. The knowledge transfer between the different categories is significant, meaning that what you learn in cosmetics and fragrances—through both product R&D and consumer research—has a lot of spillover into hair care and skin care, and vice versa. In other words, just being in the fragrance business makes you better in beauty categories overall. In addition, fragrance is a very important part of the hair-care experience—scent alone can significantly influence consumer product preferences. And it isn’t just true in hair care, which leads to the second strategic reason to play in fine fragrances: in many household and other personal-care businesses, there were significant consumer segments that cared deeply about the sensory experience. P&G could affect consumer purchase intent with the right fragrance. It soon became clear that fragrance was an important part of creating delightful consumer experiences and that P&G was the biggest fragrance user in the world. This little fine-fragrance business was important well beyond its existing size; it was crucial to building core capabilities and systems that could differentiate and create competitive advantage for brands and products across the entire corporation. So P&G not only held on to the fine-fragrances business, but also built it strategically. P&G turned the industry business model inside out by making a totally different set of strategic where-to-play and how-to-win choices. Within the fine-fragrances industry, there was a well-established way to do business: new fragrances were pushed out of the fashion studios and fragrance houses, down the fashion runway, and into department stores at Christmas time. Most new fragrance brands were launched for holiday shopping and began to decline by the next spring. It was a push-and-churn model. And in most cases, it was secondary to another, primary business: fashion. By contrast, P&G started with the consumer, hiring its own internal team of master perfumers to design fragrances against specific consumer wants and needs, as well as brand concepts. It partnered with the very best fragrance-house perfumers and designers. Before long, P&G became the preferred innovation partner in the fine-fragrance space. P&G brands are consumer-centric, concept-led, and designed to delight consumers. As it dedicated time and attention to the fine-fragrance business, P&G attracted the best agency partners and won numerous awards for advertising, marketing, and packaging. It built product portfolios that expanded and strengthened its consumer user base. It built brands that became leaders in their segments. Another norm for the fragrance industry was to compete most aggressively within the high-end women’s market. Rather than go head-to-head with the biggest players, the P&G fine-fragrance team decided to attack along the line of least expectation and least resistance—in men’s fragrances with Hugo Boss and in younger, sporty fragrances through a partnership with Lacoste. The competition was focused on women’s classic and fashion fragrances, where existing sales and profits were. Choosing a different place to play gave the fine-fragrance team the time and opportunity to test its strategy and business model, to hone its capabilities, and to build confidence that it could win. To win in fine fragrances, the team leveraged all it could from P&G’s core capabilities. It used P&G brand-building expertise to assess the strength and value of brands to determine which fashion brands to license and how much to pay for them. It used an understanding of the discipline of strategy to match its choices with the choices of the licensors, creating greater value for both. On the innovation front, world-leading expertise with scents enabled P&G to create licensed-brand products that were uniquely appealing to consumers and that could last beyond a season. And P&G’s scale as the world’s largest purchaser of fragrances enabled it to buy critical and expensive perfume ingredients at lower cost than any competitors could. With all these capabilities applied full force to the business, P&G built a fragrance house with licenses from Dolce & Gabbana, Escada, Gucci, and others. In the process, P&G became one of the largest and most profitable fine-fragrance businesses in the world, less than two decades after a modest entry into the industry. Staying in the fine-fragrances business is a choice that seemed counterintuitive at first and required a new way of thinking about just where to play within it, but the choice has paid huge dividends to the company overall. Some things, however, happen by way of serendipity, and the acquisition of Max Factor is a perfect case in point. Max Factor was acquired to make the P&G cosmetics business more global. That really never panned out. Max Factor did sufficiently poorly in North America that it was discontinued there. Nor did it provide much of a cosmetics platform outside North America. So, the acquisition would likely be called a failure, considering the intent of the purchase. But as it turns out, the cosmetics business came along with two businesses—a small fine-fragrances portfolio and a tiny, super-high-end Japanese skin-care business called SK-II. That fragrance portfolio became the seed of a multi-billion-dollar, world-leading fine-fragrances business. SK-II has expanded into international markets and has crossed the billion-dollar mark in global sales, with extremely attractive profitability. In this case, serendipity smiled on P&G—though it also took smart choices and hard work to realize the potential of the businesses.

- Where to play is about understanding the possible playing fields and choosing between them. It is about selecting regions, customers, products, channels, and stages of production that fit well together—that are mutually reinforcing and that marry well with real consumer needs. Rather than attempt to serve everyone or simply buy a new playing field or accept your current choices as inevitable, find a strong set of where-to-play choices. Doing so requires deep understanding of users, the competitive landscape, and your own capabilities. It requires imagination and effort. And every so often, some luck doesn’t hurt. As you work through your own choices, recall that where-to-play choices are equally about where not to play. They take options off the table and create true focus for the organization. But there is no single right answer. For some companies or brands, a narrow choice works best. For others, a broader choice fits. Or it may be that the best option is a narrow customer choice within a broad geographic segment (or vice versa). As with all things, context matters. The heart of strategy is the answer to two fundamental questions: where will you play, and how will you win there? The next chapter will turn to the second question and to the matter of creating integrated choices, in which where to play and how to win reinforce and support, rather than fight against, one another.

- WHERE-TO-PLAY DOS AND DON’TS

- Do choose where you will play and where you will not play. Explicitly choose and prioritize choices across all relevant where dimensions (i.e., geographies, industry segments, consumers, customers, products, etc.).

- Do think long and hard before dismissing an entire industry as structurally unattractive; look for attractive segments in which you can compete and win.

- Don’t embark on a strategy without specific where choices. If everything is a priority, nothing is. There is no point in trying to capture all segments. You can’t. Don’t try.

- Do look for places to play that will enable you to attack from unexpected directions, along the lines of least resistance. Don’t attack walled cities or take on your strongest competitors head-to-head if you can help it.

- Don’t start wars on multiple fronts at once. Plan for your competitors’ reactions to your initial choices, and think multiple steps ahead. No single choice needs to last forever, but it should last long enough to confer the advantage you see

- Do be honest about the allure of white space. It is tempting to be the first mover into unoccupied white space. Unfortunately, there is only one true first mover (as there is only one low-cost player), and all too often, the imagined white space is already occupied by a formidable competitor you just don’t see or understand.

-

Suffice it to say, Minute Maid and Tropicana fought their new competitor as though their lives depended on it—which, given P&G’s reputation, was not likely an exaggeration. P&G always aimed for leading market share in each category—and sometimes, but rarely, settled for second place. So if P&G was allowed to succeed, the competitors saw, one of them would probably die and both could be displaced. By all appearances, Minute Maid and Tropicana treated the Citrus Hill launch as a battle for survival and not just another competitive foray. For P&G, this wasn’t like entering a new category against hundreds of small cloth-diaper producers with the launch of Pampers, or like mop manufacturers with Swiffer. Citrus Hill was going up against two gigantic, deep-pocketed, and entrenched competitors. Sadly for P&G, the orange juice wars turned out to be a humbling experience. Citrus Hill never made meaningful headway against the defenses of Minute Maid and Tropicana, and P&G exited the business after a decade of frustration. The final insult was that the brand had to be shuttered, rather than sold, because no one could be found to buy it. The only bright spot was that P&G made a nice annual profit post-exit, by licensing the calcium technology to its two former competitors. It turned out that both firms were happy to pay to add an attractive benefit to their existing offerings.

- With the development of these new film-wrap technologies, P&G was faced with a series of choices about where to play and how to win. The challenge was to find a way to win, rather than just compete, with these new technologies. Finding the answer meant taking a new and creative approach to what winning could mean and how P&G could win in a different way. The how-to-win choice had to be made thoughtfully with an understanding of the full playing field. The result was a first-of-its-kind partnership between P&G and Clorox—a partnership that made both companies stronger and created a billion-dollar, category-leading brand.

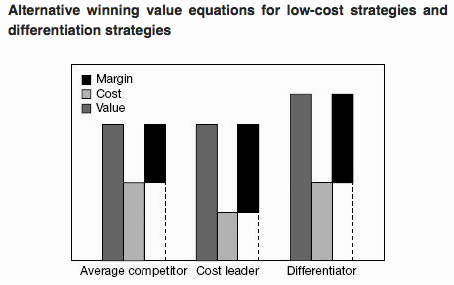

- Where to play is half of the one-two punch at the heart of strategy. The second is how to win. Winning means providing a better consumer and customer value equation than your competitors do, and providing it on a sustainable basis. As Mike Porter first articulated more than three decades ago, there are just two generic ways of doing so: cost leadership and differentiation.

- In cost leadership, as the name suggests, profit is driven by having a lower cost structure than competitors do. Imagine that companies A, B, and C all produce widgets for which customers will gladly pay $100. The products are comparable, so if one company charges more for its product than the others do, most customers will elect not to buy it in favor of the less expensive versions. Company B and company C have comparable cost structures and produce the widgets for $60, earning a $40 margin. Company A has a lower cost structure for producing essentially the same product and is able to do so for $45, producing a $55 margin. In this instance, company A is the low-cost leader and has a dramatic advantage over its competitors. The low-cost player doesn’t necessarily charge the lowest prices. Low-cost players have the option of underpricing competitors, but can also reinvest the margin differential in ways that create competitive advantage. Mars is a great example of this approach. Since the 1980s, it has held a distinct cost advantage over Hershey’s in candy bars. Mars has chosen to structure its range of candy bars such that they can be produced on a single super-high-speed production line. The company also utilizes less-expensive ingredients (by and large). Both of these choices greatly reduce product cost. Hershey’s and other competitors have multiple methods of production and more-expensive ingredients and hence higher cost structures. Rather than selling its bars at a lower price (which is nearly impossible because of the dynamics of the convenience-store trade), Mars has chosen to buy the best shelf space in the candy bar rack in every convenience store in America. Hershey’s can’t effectively counter the Mars initiative; it simply doesn’t have the extra money to spend. On the strength of this investment, Mars moved from a small player to goliath Hershey’s main rival, competing for overall market share leadership. While all companies make efforts to control costs, there is only one low-cost player in any industry—the competitor with the very lowest costs. Having lower costs than some but not all competitors can enable a firm to stick around and compete for a while. But it won’t win. Only the true low-cost player can win with a low-cost strategy.

-

The alternative to low cost is differentiation. In a successful differentiation strategy, the company offers products or services that are perceived to be distinctively more valuable to customers than are competitive offerings, and is able to do so with approximately the same cost structure that competitors use. In this case, companies A, B, and C produce widgets and all do so for $60 per widget. But while customers are willing to pay $100 for widgets from company A or B, they are willing to pay $115 for company C’s widgets, because of a perception of greater quality or more-interesting designs. Here, company C has a $15 higher margin than its competitors and a substantial advantage over them. In this type of strategy, different offerings have different consumer value equations and different prices associated with them. Each brand or product offers a specific value proposition that appeals to a specific group of customers. Loyalty emerges where there is a match between what the brand distinctively offers and the consumer personally values. In the hotel industry, for instance, one consumer would have a much higher willingness to pay for a service-oriented offering, like Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts, while another would more highly value a unique, boutique experience, like the Library Hotel in New York. Differentiation between products is driven by the activities of the firm: product design, product performance, quality, branding, advertising, distribution, and so on. The more a product is differentiated along a dimension consumers care about, the higher price premium it can demand. So, Starbucks can charge $3.50 for a cappuccino, Hermès can charge $10,000 for a Birkin bag, and they can do so largely irrespective of input costs.

- All successful strategies take one of these two approaches, cost leadership or differentiation. Both cost leadership and differentiation can provide to the company a greater margin between revenue and costs than competitors can match—thus producing a sustainable winning advantage. This is ultimately the goal of any strategy.

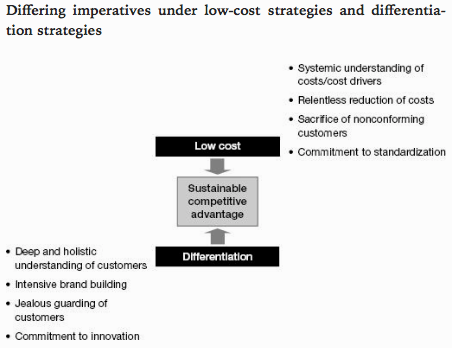

- Because markets are dynamic and new competitors find unexpected and innovative ways to deliver value, the companies that pursue low-cost and differentiation at the same time are eventually forced to choose (as IBM was, when Hitachi and Fujitsu Microelectronics entered mainframe computing with much lower cost strategies or as eBay has been forced to do, in the face of Craigslist and other alternatives). It is very difficult to pursue both cost leadership and differentiation, because each requires a very specific approach to the market.

- In other words, life inside a cost leader looks very different from life inside a differentiator. In a cost leader, managers are forever looking to better understand the drivers of costs and are modifying their operations accordingly. In a differentiator, managers are forever attempting to deepen their holistic understanding of customers to learn how to serve them more distinctively. In a cost leader, cost reduction is relentlessly pursued, while in a differentiator, the brand is relentlessly built. Customers are seen and treated very differently. At a cost leader, nonconforming customers—that is, customers who want something special and different from what the firm currently produces—are sacrificed to ensure standardization of the product or service, all in the pursuit of cost-effectiveness. At a differentiator, customers are jealously guarded. If customers indicate a desire for something different, the firm tries to design a new offering that the customers will adore. And if a customer leaves, the departure drives a stake in the heart of the firm, indicating a failure of the strategy with that customer. It is as simple as the difference between Southwest Airlines and Apple. If, as a customer, you say to Southwest, “I really would like advance seat selection, interline baggage checking, and to fly into O’Hare not Midway when I go to Chicago,” Southwest will say, “Great, you should try United Airlines.” At Apple, if customers say, “Wow, this iPad is beautiful,” Apple will take that as a cue to bring out an even prettier next-generation iPad.

-

Both cost leadership and differentiation require the pursuit of distinctiveness. You don’t get to be a cost leader by producing your product or service exactly as your competitors do, and you don’t get to be a differentiator by trying to produce a product or service identical to your competitors’. To succeed in the long run, you must make thoughtful, creative decisions about how to win. In doing so, you enable your organization to sustainably provide a better value equation for consumers than competitors do and create competitive advantage.

- Competitive advantage provides the only protection a company can have. A company with a competitive advantage earns a greater margin between revenue and cost than other companies do for engaging in the same activity. A firm can use that additional margin to fight those other companies, which will not have the resources to defend themselves. It can use that advantage to win. Low cost and differentiation seem like simple concepts, but they are very powerful in terms of keeping companies honest about their strategies. Many companies like to describe themselves as winning through operational effectiveness or customer intimacy. These sound like good ideas, but if they don’t translate into a genuinely lower cost structure or higher prices from customers, they aren’t really strategies worth having. Across its categories and markets, P&G pursues branded differentiation strategies that allow it to command price premiums.

- Strategic capability is required for thinking your way out of difficult positions—like the one that faced the Gain laundry detergent team. At one point, Gain was virtually out of business—with distribution in just a few southern states. In fact, in the late 1980s, the Gain brand manager, John Lilly, sent a memo to then-CEO John Smale recommending that the brand be discontinued. Smale sent the memo back to Lilly with his full response written across the top: “John, one more try please.” Smale didn’t dispute the logic of the memo; he just wanted to give Gain another chance, even if it was a long shot. The Gain team (then led by subsequent brand manager Eleni Senegos) set out to redefine the Gain where-to-play and how-to-win choices, giving it one more try. Again, the team started with the consumer. Tide was the overwhelming market leader and largely owned the all-purpose-cleaning position. But the consumer segmentation data showed that a small but passionate group of consumers wasn’t well served by Tide or by any other competitive product. This segment cared very much about the sensory laundry experience—about the scent of the product in the box, the scent during the washing process, and especially the scent of clean clothes. Scent was the proof of clean for these consumers. At the time, there wasn’t a brand positioned for scent seekers, people who want a dramatic and powerful fragrance experience from the moment the box is opened through the entire wash process, out of the dryer, and into the drawer. Gain could fill that niche. Moving Gain into the scent-seeker position was possible through P&G’s expertise with fragrance across product categories. P&G, as we’ve noted, is the largest fragrance company in the world; not only does it have a robust business in fine fragrances, but virtually every P&G product has a distinctive fragrance, geared to create a unique and desirable user experience. The scent-seeker positioning played to P&G’s ability to create scents that are robust at all of those points in the process, and to make that clear in every way. The package was totally changed to be bright, loud, and in-your-face. It really says that if you like big, bold scents, this is the product for you. The Gain team plugged away at that positioning on the shelf and in advertising. Gain is now one of P&G’s billion-dollar brands, even though it is only sold in the United States and Canada. And the impetus was Smale’s push to think again, to find a new way to win.

- Where-to-play and how-to-win choices do not function independently; a strong where-to-play choice is only valuable if it is supported by a robust and actionable how-to-win choice. The two choices should reinforce one another to create a distinctive combination. Think of Olay, in which the new where-to-play (thirty-five- to forty-nine-year-old women interested in age-defying skin-care products) was perfectly matched with the new how-to-win (in the high-end masstige segment with mass-retail partners and products that fight the seven signs of aging). With Bounty, narrowing where to play to North America enabled the team to decide how to win around North American consumers’ different needs. In the Glad joint venture, some where-to-play choices (like creating a new P&G wraps and trash bags category) would have made it difficult to win with consumers, given the nature of competition in the category and the likely response of competitors. Instead, the company found a how-to-win choice, a joint venture with a competitor, and the venture created new value for consumers and for both P&G and Clorox. The where and how were considered together, and a very different approach was created.