Narrative and Numbers - Aswath Damodaran

Note: While reading a book whenever I come across something interesting, I highlight it on my Kindle. Later I turn those highlights into a blogpost. It is not a complete summary of the book. These are my notes which I intend to go back to later. Let’s start!

-

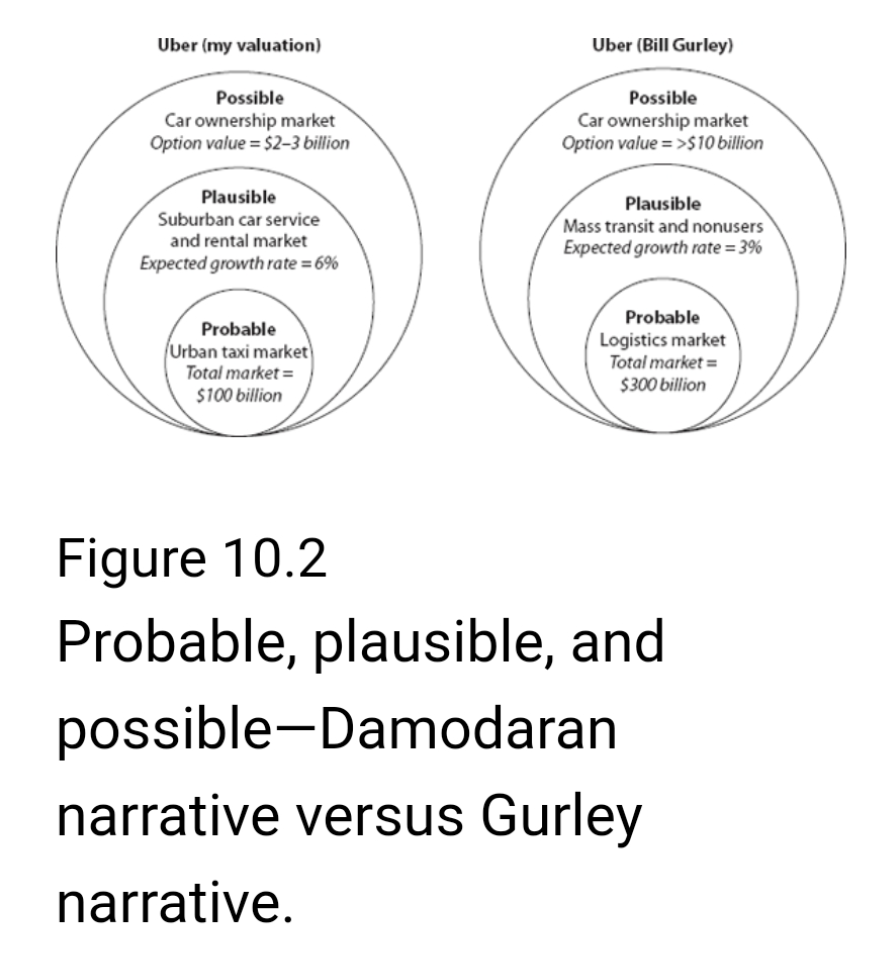

How can you adapt and control storytelling in the context of valuing businesses and making investments? You begin by understanding the company you are valuing, looking at its history, the business it operates in, and the competition, both current and potential, it may face. You then have to introduce discipline into your storytelling by subjecting your story to what I call the 3P test, starting with the question of whether your story is possible, a minimal test that most stories should meet; moving on to whether it is plausible, a tougher test to overcome; and closing with whether it is probable, the most stringent of the tests

-

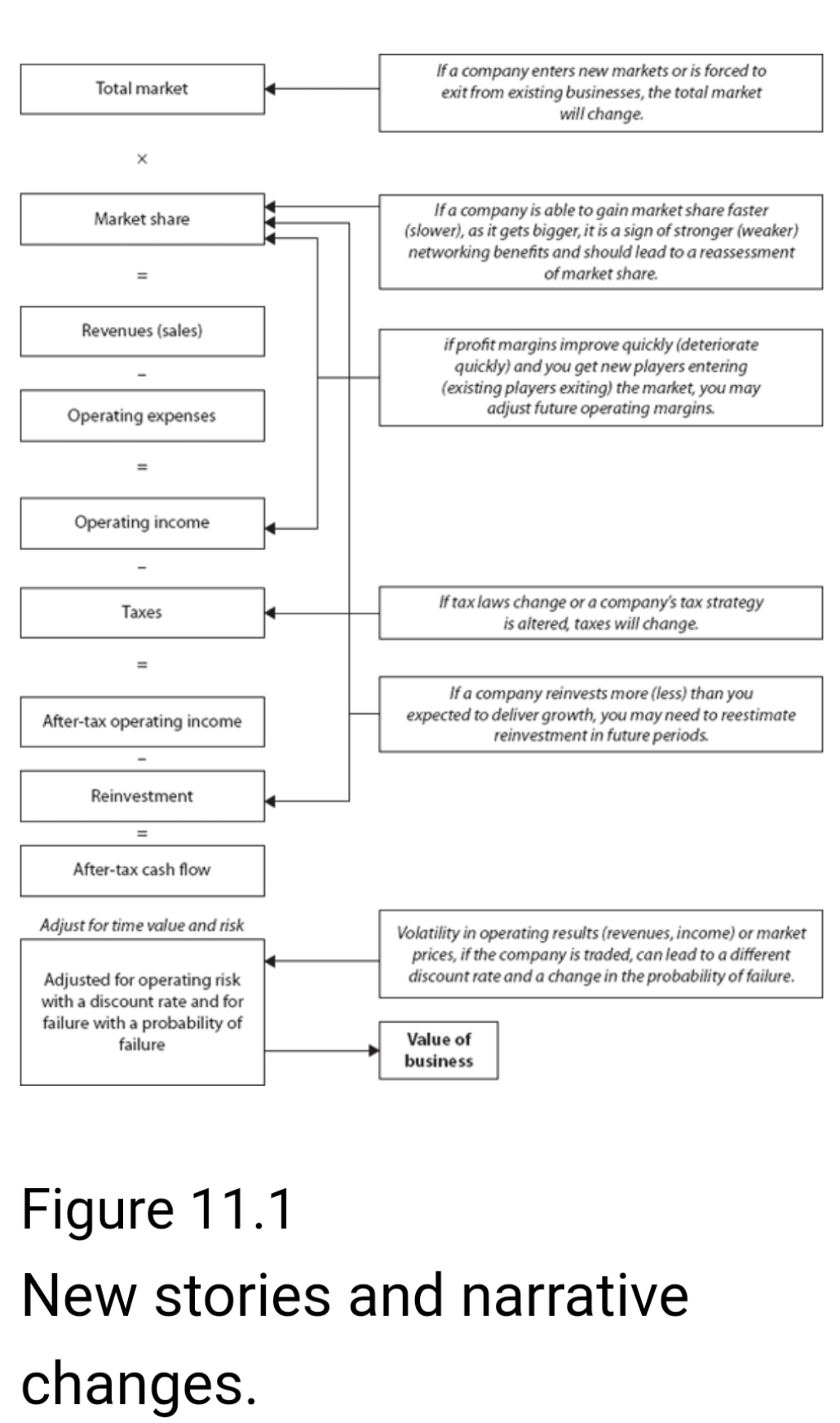

Classify narrative alterations into three groups: narrative breaks, in which real-life events decimate or end a story; narrative changes, in which actions or outcomes lead you to alter the story that you are telling in fundamental ways; and narrative shifts, in which occurrences on the ground don’t change the basic story but do alter some of its details in good or bad ways

- A business narrative needs the following ingredients to work:

- It has to be simple: A simple story that makes sense will leave a more lasting impression than a complex story in which it is tough to make connections.

- It has to be credible: Business stories need to be credible for investors to act on them. If you are a skillful enough storyteller you may be able to get away with leaving unexplained loose ends, but those loose ends will eventually imperil your story and perhaps your business.

- It has to inspire: Ultimately, you don’t tell a business story to win creativity awards but to inspire your audience (employees, customers, and potential investors) to buy into the story.

- It should lead to action: Once your audience buys into your story, you want them to act, employees by choosing to come to work for your company, customers by buying your products and services, and investors by putting their money in your business.

-

The bottom line for a business narrative is that it is less about specifics and details and more about big picture and vision

- The lines between the possible, plausible, and probable are not always easy to draw, but one simple technique I have found useful is to think about the distinction between impossible, implausible, and improbable. Impossible and improbable are quantifiable, the first because you are assigning a zero probability to an event happening and the latter because you are attaching a probability (albeit a low one) that an event will happen. Implausible lies in the muddled middle, since proving that it cannot happen is not feasible and attaching a probability judgment to it is just as difficult

-

Any perpetual growth rate that exceeds the nominal growth rate of the economy is impossible.

-

No matter how successful you think a company will be in capturing market share, its eventual market share cannot exceed 100 percent.

-

Assume you are telling your story about a company that operates in a very competitive sector, and in your story, you see the company capturing a higher market share of this market. That is a plausible story, but not if you also claim that the company will be able to simultaneously raise prices on its products and have higher profit margins. After all, in a competitive product market, if you raise prices, you will lose market share, not gain it. With almost every part of your narrative, you have to think through how others will react and whether your results will continue to hold, given their reactions. If your narrative is built around cutting employee wages and benefits, and thus increasing profits, it will work only if employees will continue to work for you at the reduced compensation

- It is natural to want to hold onto your narrative and to keep it unchanged, even in the face of contradictions. Rather than let hubris keep you wedded to your old story, you should think about how your narrative is altered by events, small and large

-

The process of building up a macro narrative shares some features with the company narrative process that we described in earlier chapters and deviates from others. It starts with an identification and understanding of the macro variable in question (commodity, cyclicality, or country) and it has to be followed by an assessment of how the company you are trying to value is affected by movements in the macro variable. The final step is a judgment you have to make as to how much you want your valuation to rest on your forecasts of the macro variable and how you plan to build that linkage into your numbers

-

The macro variables that you can build corporate stories around are many, but the three that are most used are commodity, cyclicality, and country. In the first (commodity), you build a story around a commodity-driven company, with the commodity price being the central variable and the company’s expected response to commodity price changes determining value. In the second (cyclicality), the valuation is of a company, and the primary driver of operating numbers is the overall health or lack thereof of the economy. Thus, your story starts with the economy, with the company woven into it, and requires that you link your company’s prospects to how well or badly the economy does. In the third (country), the driver of value for the company is the country in which it is incorporated and where much of its operations are centered, with your views on the country having a much bigger impact on your value than your views on the company

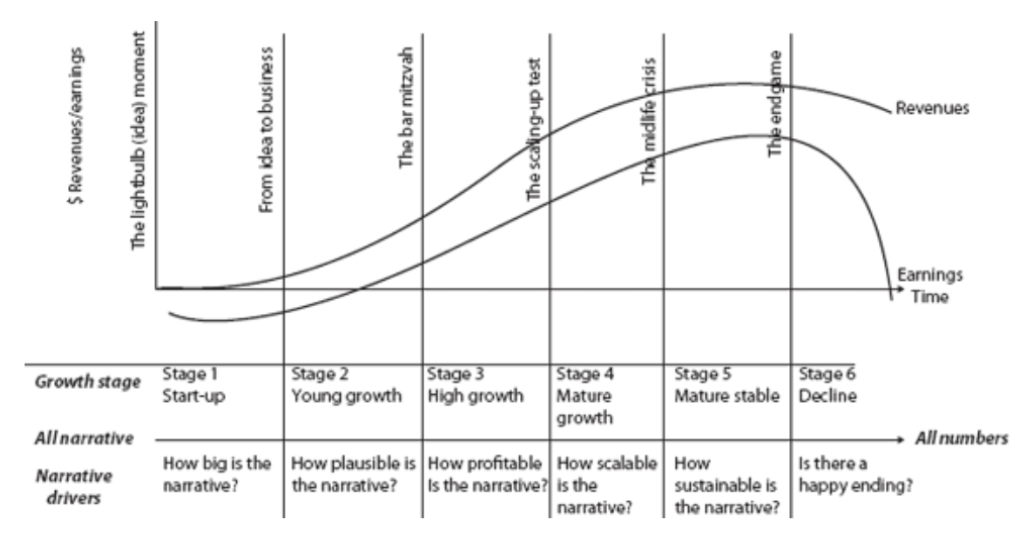

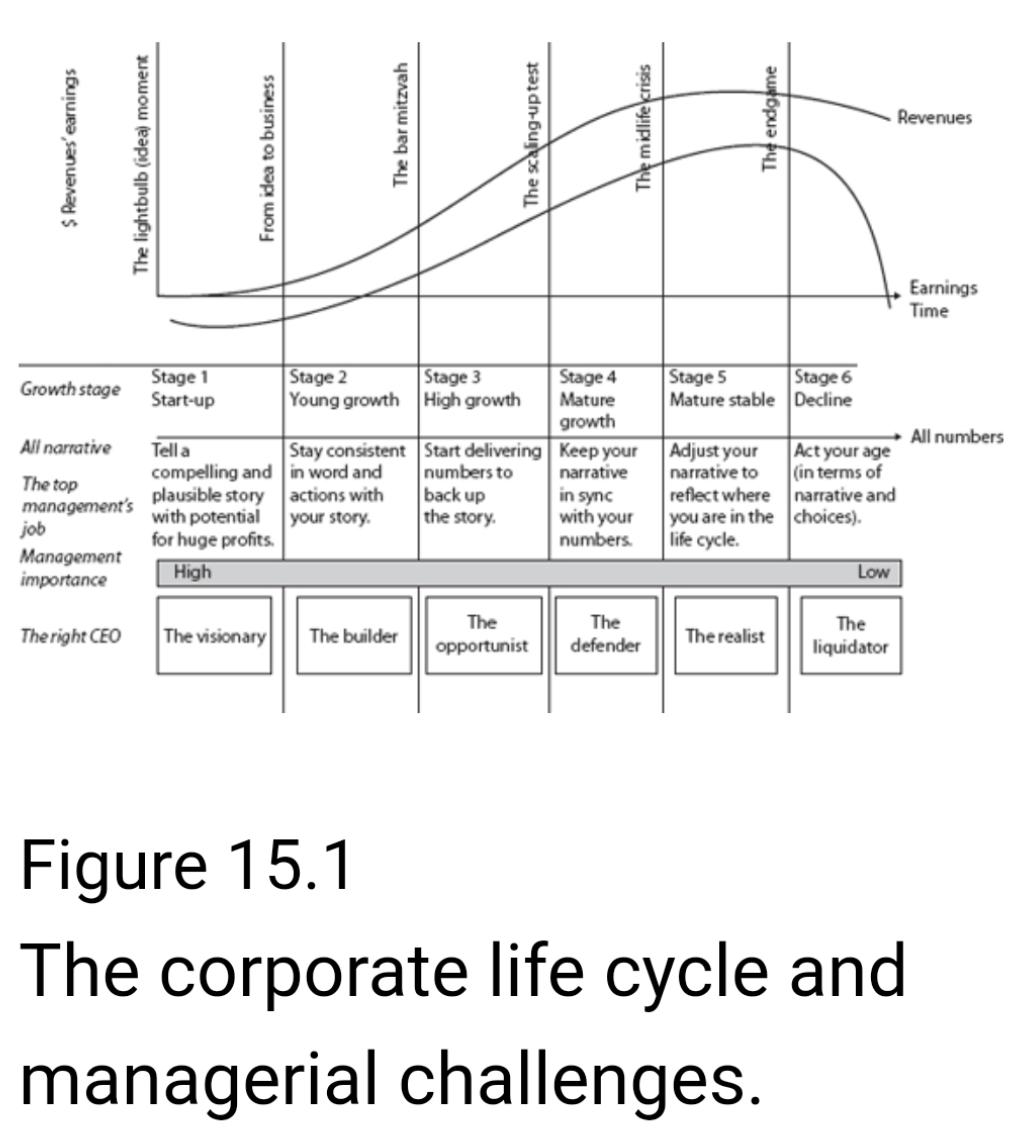

- While the challenges that management faces can vary across the life cycle, there are some constants that emerge from looking at successful businesses and their leaders over time.

- Control the story: Managing is not just about delivering numbers and meeting analyst expectations. It is about telling a story about the business that allows investors to understand not only its history but where you (as the leader) plan to take it in the future. If top managers do not craft a credible story about the company, investors and analysts will step into the vacuum and craft their own stories, leaving the company playing a game that is not of its own choosing.

- Stay consistent with that story: Managers are also judged on whether their story stays consistent over time. That does not mean that you can never change your story, as you often must in response to events, but it does mean that if your story changes, you have to explain why and how. If your narrative changes from period to period, with no explanation and perhaps to be in sync with whatever investors and customers are most enamored with in that period, your story will lose credibility and risk being displaced by alternate ones.

- Act in accordance with the story: As managers make decisions on where to invest, how to fund those investments, and how much cash to return to investors, they will be watched closely to see whether their actions match up to the story they have told about the business. A CEO who frames a narrative about his or her business being a global player but never invests or seeks out opportunities in foreign markets will find that investors stop believing that story.

- Deliver results that back up the story: As a CEO, you can tell a great story and stay consistent with it over time and with your actions, but if the results don’t measure up, you will still be found wanting. If your numbers consistently tell a different story than the one that you have been offering to markets, the numbers will win out. Thus, a CEO who pushes a high-growth story to investors while delivering flat revenues will have to either change his or her story or risk being ignored