Only the Paranoid Survive - Andrew S. Grove

Note: While reading a book whenever I come across something interesting, I highlight it on my Kindle. Later I turn those highlights into a blogpost. It is not a complete summary of the book. These are my notes which I intend to go back to later. Let’s start!

-

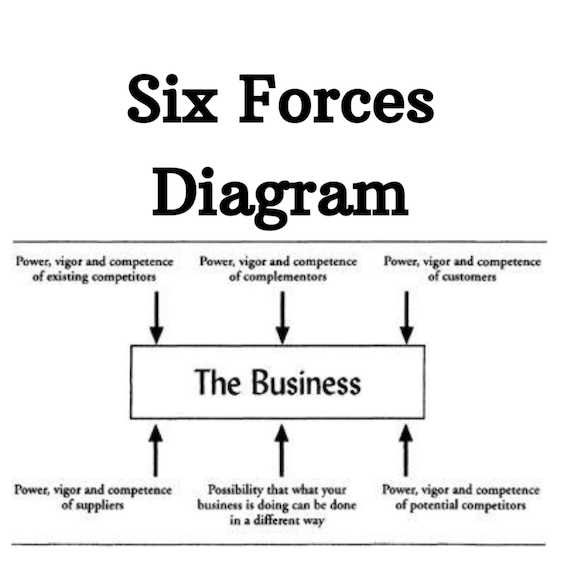

A very large change in one of these six forces a “10X” change

-

A “10X” Force: When a change in how some element of one’s business is conducted becomes an order of magnitude larger than what that business is accustomed to, then all bets are off. There’s wind and then there’s a typhoon, there are waves and then there’s a tsunami. There are competitive forces and then there are super competitive forces

-

To manage a business in the face of a “10X” change is very, very difficult

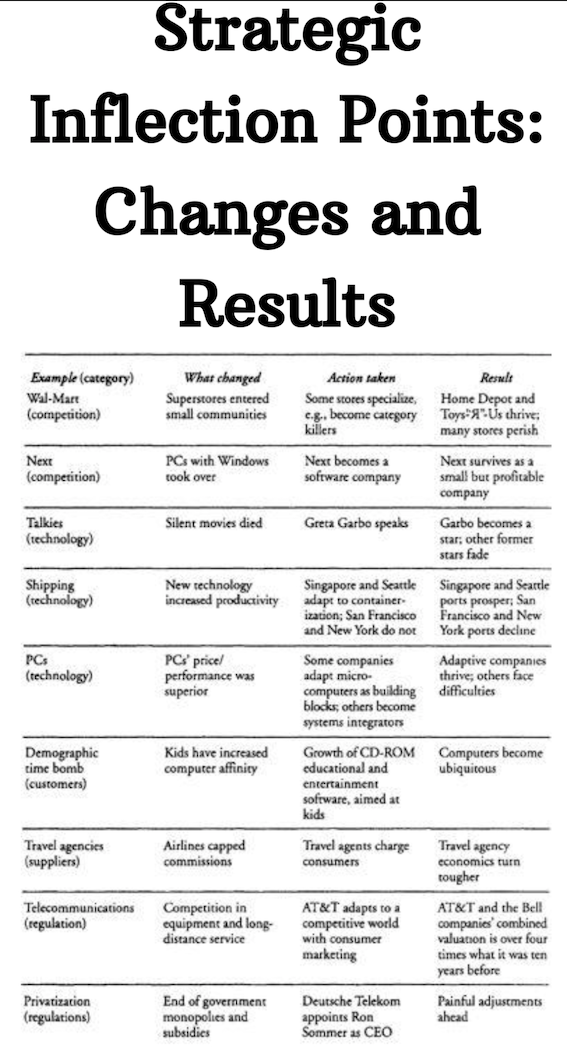

- A strategic inflection point is when the balance of forces shifts from the old structure, from the old ways of doing business and the old ways of competing, to the new

-

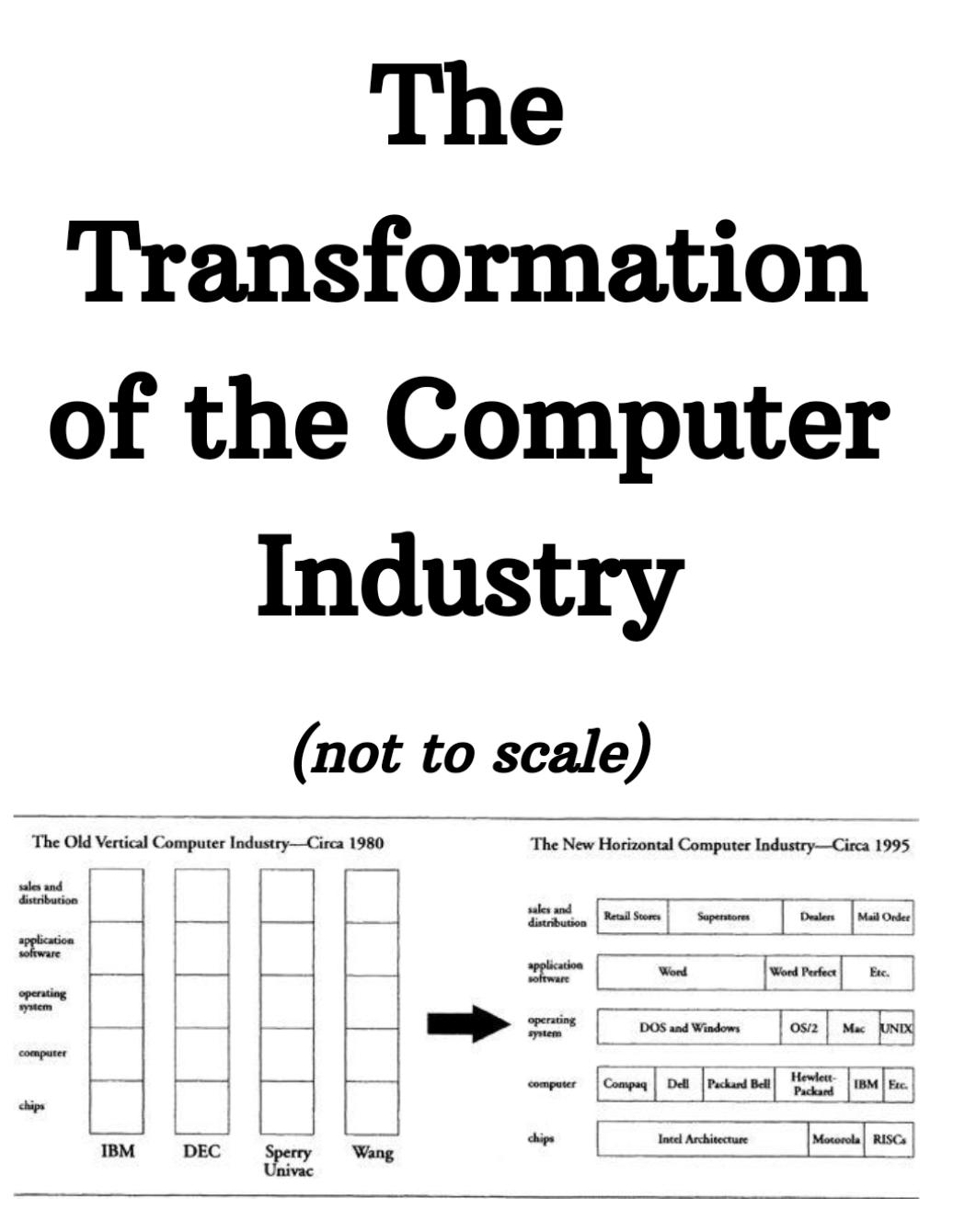

A company competed in this industry as one vertical proprietary block against all other computer companies’ vertical proprietary blocks

-

But as the microprocessor became the basic building block of the industry, the economics of mass production kicked in and manufacturing computers became extremely cost-effective, making the PC an enormously attractive tool in both home and business settings. Over time, this changed the entire structure of the industry and a new horizontal industry emerged. In this new model, no one company had its own stack. A consumer could pick a chip from the horizontal chip bar, pick a computer manufacturer from the computer bar, choose an operating system out of the operating system bar, grab one of several ready-to-use applications off the shelf at a retail store or at a computer superstore and take the collection of these things home

-

The “Intel Inside” program begun in 1991 established a mindset in computer users that they were, in fact, Intel’s customers, even though they didn’t actually buy anything from us. It was an attitude change, a change we actually stimulated, but one whose impact we at Intel did not fully comprehend

-

The key activity that’s required in the course of transforming an organization is a wholesale shifting of resources from what was appropriate for the old idea of the business to what is appropriate for the new

-

Assigning or reassigning resources in order to pursue a strategic goal is an example of what I call strategic action. I’m convinced that corporate strategy is formulated by a series of such actions, far more so than through conventional top-down strategic planning

-

Strategic plans are statements of what we intend to do. Strategic actions are steps we have already taken or are taking which suggest our longer-term intent

-

Strategic plans sound like a political speech. Strategic actions are concrete steps. They vary: They can be the assignment of an up-and-coming player to a new area of responsibility; they can be the opening of sales offices in a portion of the world where we haven’t done business before; they can be a cutback in the development effort that deals with a long-pursued area of our business. All of these are real and suggest directional changes

-

While strategic plans are abstract and are usually couched in language that has no concrete meaning except to the company’s management, strategic actions matter because they immediately affect people’s lives. They change people’s work, as was the case when we shifted capacity from memory production to microprocessor production and our sales force had a different product mix. They cause consternation and raise eyebrows, as did the transfer of the Intel manager from the tried-and-true microprocessor business to an ambiguous new area. Strategic plans deal with events that are so far in the future that they have little relevance to what you actually have to do today. So they don’t command true attention

-

Strategic actions, however, take place in the present. Consequently, they command immediate attention. Their power comes from this very aspect. Even if any one strategic action changes the trajectory on which the corporation moves by only a few degrees, if those actions are consistent with the image of what the company should look like when it gets to the other side of the inflection point, every one of them will reinforce every other. That’s why I think the most effective way to transform a company is through a series of incremental changes that are consistent with a clearly articulated end result

-

A question that often comes up at times of strategic transformation is, should you pursue a highly focused approach, betting everything on one strategic goal, or should you hedge?

-

It takes every erg of energy in your organization to do a good job pursuing one strategic aim, especially in the face of aggressive and competent competition. There are several reasons for this. First, it is very hard to lead an organization out of the valley of death without a clear and simple strategic direction. After all, getting there sapped the energy of your organization; it demoralized your employees and often set them against one another. Demoralized organizations are unlikely to be able to deal with multiple objectives in their actions. It will be hard enough to lead them out with a single one

-

If competition is chasing you (and they always are—this is why “only the paranoid survive”), you only get out of the valley of death by outrunning the people who are after you. And you can only outrun them if you commit yourself to a particular direction and go as fast as you can. You could argue that, since they are chasing you, you should give yourself all sorts of alternative directions—in other words, hedge. I say, “No.” Hedging is expensive and dilutes commitment. Without exquisite focus, the resources and energy of the organization will be spread a mile wide—and they will be an inch deep

-

Second, while you’re going through the valley of death, you may think you see the other side, but you can’t be sure whether it’s truly the other side or just a mirage. Yet you have to commit yourself to a certain course and a certain pace, otherwise you will run out of water and energy before long. If you’re wrong, you will die. But most companies don’t die because they are wrong; most die because they don’t commit themselves. They fritter away their momentum and their valuable resources while attempting to make a decision. The greatest danger is in standing still

-

Clarity of direction, which includes describing what we are going after as well as describing what we will not be going after, is exceedingly important at the late stage of a strategic transformation. Much as in the middle of the strategic inflection process you needed to let chaos reign in order to explore your alternatives, to lead your organization out of the resulting ambiguity and to energize your staff toward a new direction, you must rein in chaos

-

You can’t hedge in a choice of direction and you can’t hedge in your commitment to it. If you do, your people will be confused and after a while they will throw up their hands in resignation. Not only will you lose direction, but you will continue to sap the energy of your organization as well

-

Communicating strategic change in an interactive, exposed fashion is not easy. But it is absolutely necessary

-

It seems that companies that successfully navigate through strategic inflection points have a good dialectic between bottom-up and top-down actions. Bottom-up actions come from the ranks of middle managers, who by the nature of their jobs are exposed to the first whiffs of the winds of change, who are located at the periphery of the action where change is first perceived (remember, snow melts at the periphery) and who therefore catch on early. But, by the nature of their work, they can only affect things locally: The production planners can affect wafer allocation but they can hardly affect marketing strategy. Their actions must meet halfway the actions generated by senior management. While those managers are isolated from the winds of change, once they commit themselves to a new direction, they can affect the strategy of the entire organization. The best results seem to prevail when bottom-up and top-down actions are equally strong

-

The other side of the valley of death represents a new industry order that was hard to visualize before the transition. Management did not have a mental map of the new landscape before they encountered it. Getting through the strategic inflection point required enduring a period of confusion, experimentation and chaos, followed by a period of single-minded determination to pursue a new direction toward an initially nebulous goal. It required listening to Cassandras, deliberately fostering debates and constantly articulating the new direction, at first tentatively but more clearly with each repetition. It required casualties and personal transformation; it required accepting the fact that not all would survive and that those who did would not be the same as they had been before

-

Beyond a doubt, going through the valley of death that a strategic inflection point represents is one of the most daunting tasks an organization has to endure. But when “10X” forces are upon us, the choice is taking on these changes or accepting an inevitable decline, which is no choice at all