Radical Candor - Kim Scott

I recently completed Kim Scott’s ‘Radical Candor: Be a Kickass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity’. She wrote this book on her Radical Candor method which she designed after a highly successful management career at Google followed by Apple, where she developed a class on optimal management.

Before reading this book you might want to check out these 2 blogposts which led to this book:

Radical Candor — The Surprising Secret to Being a Good Boss On Receiving (and Truly Hearing) Radical Candor

I am sharing my favourite parts from the book here.

-

Guidance, team, and results: these are the responsibilities of any boss. This is equally true for anyone who manages people — CEOs, middle managers, and first-time leaders

-

As a manager you have fulfill your three responsibilities: 1) to create a culture of guidance (praise and criticism) that will keep everyone moving in the right direction 2) to understand what motivates each person on your team well enough to avoid burnout or boredom and keep the team cohesive 3) to drive results collaboratively

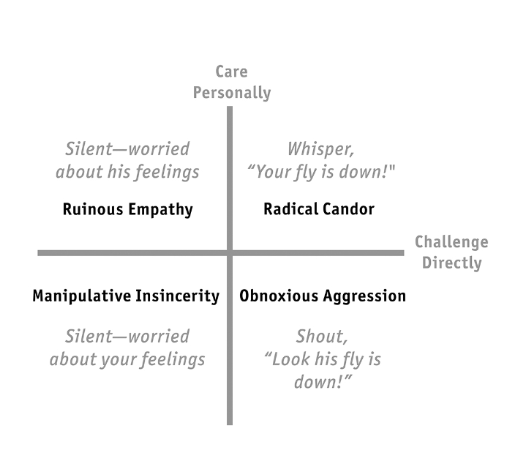

Radical candor

Radical candor

-

It turns out that when people trust you and believe you care about them, they are much more likely to 1) accept and act on your praise and criticism 2) tell you what they really think about what you are doing well and, more importantly, not doing so well 3) engage in this same behavior with one another, meaning less pushing the rock up the hill again and again 4) embrace their role on the team 5) focus on getting results

-

To help encourage a culture of radical candor in her team, Kim Scott tells a story about Toyota that she had learned in business school. Wanting to combat the cultural taboos against criticising management, Toyota’s leaders painted a big red square on the assembly line floor. New employees had to stand in it at the end of their first week, and they were not allowed to leave until they had criticised at least three things on the line. The continual improvement this practice spawned was part of Toyota’s success

-

A leader at Apple had a good way to think about different types of ambition that people on her team had so that she could be thoughtful about what roles to put people in. To keep a team cohesive, you need both rock stars and superstars, she explained. Rock stars are solid as a rock. The rock stars love their work. They have found their groove. They don’t want the next job if it will take them away from their craft. Superstars, on the other hand, need to be challenged and given new opportunities to grow constantly. You need to nurture the ambition and needs of both

-

Kim Scott learned in her career that telling people what to do does not work. There was a time when Kim’s company was obviously in need of big changes, and it had seemed like it was the fastest way forward, but it wasn’t. First, because she didn’t involve her team in decision-making; she just made the decisions herself. Second, because even after making them she didn’t take the time to explain why or to persuade the team that she had made good decisions. So, instead of executing on decisions they didn’t agree with or even understand, her team dissolved, and she realised she wasn’t going to improve results until she rebuilt it

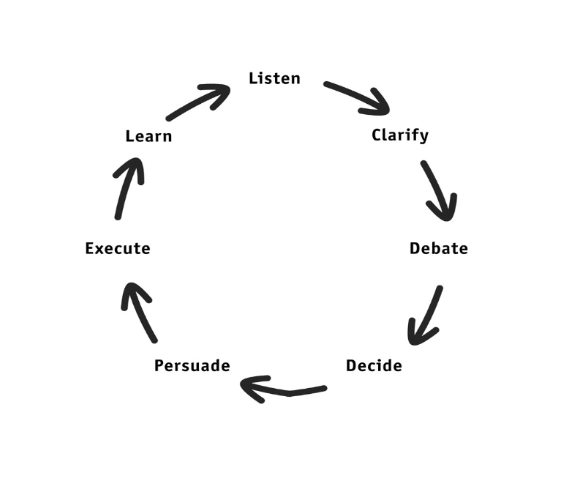

Get stuff done framework

Get stuff done framework

-

First, you have to listen to the ideas that people on your team have and create a culture in which they listen to each other. Next, you have create space in which ideas can be sharpened and clarified, to make sure these ideas don’t get crushed before everyone fully understands their potential usefulness. But just because an idea is easy to understand doesn’t mean it’s a good one. Next, you have to debate ideas and test them more rigorously. Then you need to decide — quickly, but not too quickly. Since not everyone will have been involved in the listen-clarify-debate-decide part of the cycle for every idea, the next step is to bring the broader team along. You have to persuade those who weren’t involved in a decision that it was a good one, so that everyone can execute it effectively. Then, having executed, you have to learn from the results, whether or not you did the right thing, and start the whole process over again

-

Sometimes creating a culture of listening is simply a matter of managing meetings the right way. When just a couple of people were doing all the talking at a meeting, Kim would stop and go around the table to ensure that everyone got heard. Other times, she would stand up in the next meeting and walk around, physically blocking a person who was talking too much. Sometimes she would have a quick conversation with people before a meeting, asking some to pipe up and others to pipe down. In other words, part of her job was to constantly figure out new ways to “give the quiet ones a voice”

-

Once you have created a culture of listening, the next step is to push yourself and your direct reports to understand and convey thoughts and ideas more clearly. Trying to solve a problem that hasn’t been clearly defined is not likely to result in a good solution; debating a half-baked idea is likely to kill it. As the boss, you are the editor, not the author

-

It’s important to push the people on your team to clarify their thinking and ideas so that you don’t “squish” their best thinking or ignore problems that are bothering them. It’s not just important to understand new ideas clearly; it’s equally important, and often more difficult, to understand the people to whom your team will have to explain the ideas clearly

-

Part of your job as the boss is to help people think through their ideas before submitting them to the rough-and-tumble of debate

-

The Steve Jobs story: When Steve Jobs was a kid, his neighbor showed him a rock tumbler — a can that spun on a motor. The neighbor asked Steve to gather up some ordinary rocks from the yard. He took the stones, threw them into the can, added some grit, turned on the motor, and, over the racket, asked Steve to come back two days later. When Steve returned to the noisy clatter of the garage, the neighbor turned off the contraption and Steve was astounded to see how the ordinary rocks had become beautiful polished stones. Steve would later say that when a team debated, both the ideas and the people came out more beautiful — results well worth all the friction and noise

-

Your job as a boss is to turn on that “rock tumbler.” Too many bosses think their role is to turn it off — to avoid all the friction by simply making a decision and sparing the team the pain of debate

-

McKinsey had very consciously created an “obligation to dissent”. If everyone around the table agreed, that was a red flag. Somebody had to take up the dissenting voice

-

There are times when people are just too tired, burnt out, or emotionally charged up to engage in productive debate. It’s crucial to be aware of these moments, because they rarely lead to good outcomes. Your job is to intervene and call a time-out

-

It’s tempting to end debates and make a decision too soon when a debate becomes too painful. You might be creeping up on a topic that’s been a subject of great contention. At times like this, people often look to the boss to end the suffering and make a decision. Generally your instinct is to be a peacemaker, or to get to a decision quickly. But a boss’s job is often to keep the debate going rather than to resolve it with a decision. It’s the debates at work that help individuals grow and help the team work better collectively to come up with the best answer

-

Set a “decide by” date, so everybody would know that they couldn’t lobby the project manager endlessly

-

Expecting others to execute on a decision without being persuaded that it’s the right thing to do is a recipe for terrible results. And don’t imagine that you can step in and simply tell everyone to get in line behind a decision, whether you have made it or somebody else has. Even explaining the decision is not enough, because that addresses only the logic; you have to address your listener’s emotions as well. And you must establish that the decider, whether that’s you or somebody else on your team, has credibility if you expect others to execute on the decision

-

Credibility is one of those things that is hard to articulate but you know it when you see it. Part of it is obviously knowing your subject and demonstrating a track record of sound decisions. But it also requires a third component — humility — which is sometimes in short supply. The good news is that you learned the secret to sharing your logic in high school math class: show your work. When Steve Jobs had an idea, he wouldn’t just describe the idea; he’d share how he got to it. He showed his work. This signaled that if there was a flaw in his reasoning, he wanted to know about it. And if there wasn’t, people would be more likely to accept his idea. Showing his work was what strengthened his logic and ultimately made him not only persuasive but “always getting it right”

-

Block time to execute

-

Often, execution is a solitary task. We use calendars mostly for collaborative tasks — to schedule meetings, etc. One of your jobs as a manager is to make sure that collaborative tasks don’t consume so much of your time or your team’s time that there’s no time to execute whatever plan has been decided on and accepted

-

It’s obvious that good bosses learn from mistakes and successes alike and keep improving. And yet, denial is actually the more common reaction to imperfect execution than learning

-

Ask “Is there anything I could do or stop doing that would make it easier to work with me?” If those words don’t fall easily off your tongue, find words that do. Of course, you’re not really just looking for one thing; that opening question is just designed to get things moving

-

A simple example from everyday life: instead of yelling, “You asshole!” when somebody grabs your parking space, try saying, “I’ve been waiting for that spot here for five minutes, and you just zipped in front of me and took it. Now I’m going to be late.” If you say this, you give the person a chance to say, “Oh, I’m sorry I didn’t realize, let me move.” Of course, the person might also just flip you off and say, “Tough shit.” Then you can yell with more justification, “You asshole!” :)

-

Situation, behavior, and impact applies to praise as well as to criticism

-

Giving feedback: When somebody says, “I’m so proud of you!” it’s natural to think, “Who are you to be proud of me?” Better to say, “In your presentation at this morning’s meeting (situation), the way you talked about our decision to diversify (behavior) was persuasive because you showed everyone you’d heard the other point of view (impact)”