Obviously Awesome - April Dunford

This blogpost is not an exhaustive summary of the book. Just contains the notes I took.

-

Every single marketing and sales tactic that we use in business today uses positioning as an input and a foundation. To put it another way—none of the new, cool stuff works without good positioning as a starting point

-

Positioning is the act of deliberately defining how you are the best at something that a defined market cares a lot about marketing and sales. If we fail at marketing and sales, the entire business fails

-

Like speaking Japanese slowly and loudly to a person who speaks only English, putting a bigger marketing budget behind confusing and unclear positioning doesn’t work. And it’s hard to blame the sales process when it takes several meetings for a customer to figure out what your product is, let alone whether or not they want to purchase it

-

Weak positioning diminishes the results of everything we do in marketing and sales

-

I like to describe positioning as “context setting” for products. When we encounter something new, we will attempt to make sense of it by gathering together all of the little clues we can quickly find to determine how we should think about this new thing. Without that context, products are very difficult to understand, and the whole company suffers—not just the marketing and sales teams

-

When customers encounter a product they have never seen before, they will look for contextual clues to help them figure out what it is, who it’s for and why they should care. Taken together, the messaging, pricing, features, branding, partners and customers create context and set the scene for the product

-

Context allows us to make thousands of little decisions about what we should pay attention to and what we can simply ignore. Without context to guide us, we would be overwhelmed, maybe even paralyzed by choice

-

Most products are exceptional only when we understand them within their best frame of reference. For those of us who make and sell products, the frame of reference that potential customers build around our offerings is critical to staying in business. The trouble is, making sense of all the offerings is becoming an increasingly difficult task. There are too many products, all competing for shrinking attention. With so many other offerings on the market, it’s easy for products to get lost in the noise or, worse, completely misunderstood and framed in ways that make them unappealing, redundant or merely unremarkable

-

Product creators often fall into the trap of thinking there is only one way to position an offering, and that we have no ability to shift that contextual frame of reference, especially after we have released it to market. We set out to build something (a new dessert or a new way of doing email, for example) and then almost unconsciously position our offering in that market (“dessert” or “email”). But most products can be positioned in multiple different markets. Your dessert might be better positioned as a snack, and your email solution might make more sense if it were positioned as chat. But because we never thought about positioning our product deliberately, we continue to believe there is only one way to think about it

- Without meaning to, we trap ourselves within our own context. We don’t know how to shift the framework to best communicate what our product actually is or what it does

- Trap 1: You are stuck on the idea of what you intended to build, and you don’t realize that your product has become something else

- Imagine you’re a baker and you decide you’re going to make the greatest chocolate cake the world has ever known. You probably weren’t aware of it, but the minute you decided your product was “cake,” you made a set of critical business decisions before the flour hit the bowl. These include:

- Target buyers and where you sell. You will be selling to folks looking for a fancy dessert, either directly at a bakery or food store, or to restaurants that serve fancy desserts after fancy meals

- Competitive alternatives. You will be competing with other cakes, ice creams, pies and assorted desserts

- Pricing and margin . You won’t be likely to charge much more than you would for other desserts, since you’ll be selling the cake alongside them

- Key product features and roadmap. Your potential customers eat fancy desserts, so your product differentiators will need to appeal to them (likely high-income restaurant goers, or dinner hosts looking to impress guests). You might make your cake organic or gluten free, or add fancy French salt to your caramel sauce

- Now, suppose that in your process of experimentation, you end up creating a cake that is actually quite small. It’s so small you could sell it as a self-contained, single-serving cake, so you put a little wrapper around it. You realize that you’ve actually made supreme chocolate muffins instead of better chocolate cake

- At first it might not seem like this is much of a change. The product hasn’t changed much — it’s the same batter— but almost everything else about your business has. Why? Because we changed the mental frame of reference around the product from “cake” to “muffin.” That change in context changes everything about the business:

- Target buyers and where you sell. Unlike cakes, muffins are sold at coffee shops and diners

- Competitive alternatives. You are now competing with donuts, Danishes and bagels

- Pricing and margin. Muffins sell for a buck or two, and you will be looking to sell a lot of them

- Key product features and roadmap. You are now fighting for the hearts and minds of a noble class of people who eat chocolate for breakfast. They’re likely not worried about gluten or the origin of the salt in your caramel. They might like your muffin larger or with more caramel or maybe they want it deep-fried like a hash brown (you might be laughing, but deep down I think you want to try one of those)

- So, if you were the baker, you might not see too much difference between muffins and cake—the product is essentially the same, right? However, choosing to make muffins or cake results in two fundamentally different business models, with different ways of making revenue

- As product creators, we need to understand that the choices we make in positioning and context can have a massive impact on our businesses—for better or worse

- Imagine you’re a baker and you decide you’re going to make the greatest chocolate cake the world has ever known. You probably weren’t aware of it, but the minute you decided your product was “cake,” you made a set of critical business decisions before the flour hit the bowl. These include:

- Trap 2: You carefully designed your product for a market, but that market has changed

- Your product exists within a market context—simple enough. Trouble is, markets, and the way customers perceive them, are constantly changing. Markets are made up of competitors who are constantly evolving their offerings, often in response to shifts in technology, customer preferences, economic conditions and regulatory requirements

- Sometimes a product that was well positioned in a market suddenly becomes poorly positioned, not because the product itself has changed, but because markets around the product have shifted

- Suppose again that you’re a baker and you’ve been in the muffin business for a while. Over time, your specialty has become extraordinarily healthy muffins filled with nuts, seeds and dates. You’ve been positioning your muffin as a great breakfast for folks on a diet who want an alternative to the empty calories of a donut. For years, you’ve sold your “diet muffin” to pudgy workers from the office next door

- Then a bakery opens across the street and your office workers aren’t coming to you as often as they used to. You decide to check out the competition and discover a massive crowd that includes not only your former customers but also buff athletes from the gym down the street and a group of stylish moms. When it’s your turn to order, you get what everyone else is ordering. You’re stunned to discover the hit product at this bakery is just like yours—it’s full of nuts, seeds and dates… the ingredients are almost identical! But this muffin isn’t positioned as a “diet muffin.” In fact, they don’t even call it a muffin. It’s a “gluten-free paleo snack.”

- In this case, you had a great product but failed to adjust the positioning as markets around the product shifted. In the past, healthy eaters might have thought of themselves as “being on a diet,” but that concept shifted over time as eating habits changed and trendy diets emerged. Now, your once-popular “diet muffin” seems out of date and irrelevant to bodybuilders and trendy moms and eventually even to schlumpy desk jockeys. You were trapped in your original positioning, even though the market had moved on

- For startups and tech companies, this problem is very common. Our markets are complex, overlapping and shifting rapidly. Our customers operate in a context that is often quite different from our startup or tech bubble. It’s easy to miss a shift that impacts nurses, housekeepers, insurance agents, restaurant workers or manufacturers while we’re drinking espresso and staring at our MacBooks in our exposed-brick, open-plan offices

- Trap 1: You are stuck on the idea of what you intended to build, and you don’t realize that your product has become something else

-

The common failure in both of these traps is not deliberately positioning the product. We stick with a “default” positioning, even when the product changes or the market changes. I believe this happens because we haven’t been taught that every product can be positioned in multiple ways and often the best position for a product is not the default. We have never been taught that positioning is a deliberate business choice that requires time, attention and, importantly, a systematic process

- Great positioning takes into account all of the following:

- The customer’s point of view on the problem you solve and the alternative ways of solving that problem

- The ways you are uniquely different from those alternatives and why that’s meaningful for customers

- The characteristics of a potential customer that really values what you can uniquely deliver

- The best market context for your product that makes your unique value obvious to those customers who are best suited to your product

- These are the Five (Plus One) Components of Effective Positioning:

- Competitive alternatives. What customers would do if your solution didn’t exist

- Unique attributes. The features and capabilities that you have and the alternatives lack

- Value (and proof). The benefit that those features enable for customers

- Target market characteristics. The characteristics of a group of buyers that lead them to really care a lot about the value you deliver

- Market category. The market you describe yourself as being part of, to help customers understand your value

- (Bonus) Relevant trends. Trends that your target customers understand and/or are interested in that can help make your product more relevant right now

- Competitive alternatives

- The positioning statement exercise includes a space for defining a competitor or competing product. For many products, however, there can be several competitive alternatives and not all of them will be “products” per se. Alternatives to your product can be “hire an intern to do it,” “use a spreadsheet” or even “suffer along with the problem and do nothing.”

- The competitive alternative is what your target customers would “use” or “do” if your product didn’t exist

- Our customers often do not know nearly as much about the universe of potential solutions to a problem as we do. As product creators, we need to be experts in the different solutions that exist in a market, including the advantages and disadvantages of choosing them

- It’s important to really understand what customers compare your solution with, because that’s the yardstick they use to define “better.” For example, your solution might be much easier to use than the product that other startups are selling, but if the real alternative in the mind of a customer is Excel, you can’t say your product is easier to use unless it is easier to use than a spreadsheet

- Unique attributes

- Unique attributes are capabilities or features that your offering has that the competitive alternatives do not have

- Your unique attributes are your secret sauce, the things you can do that the alternatives can’t

- It’s the list of capabilities that you have and the alternatives don’t. For technology companies, these are often technical features, but unique attributes could also be things like your delivery model (such as installed on-premise vs. software as a service), your business model (think Rent the Runway upending retail by leasing instead of selling special-occasion wear) or your specific expertise (perhaps you have a dozen international banks as clients and therefore understand their business better than others in the market). In my database-turned-data-warehouse example, our key unique attribute was our patented query algorithm

- Sometimes, traditional positioning statements try to capture this idea under the label “differentiator.” In general, you will have many differentiators. The key is to make sure they are different when compared with the capabilities of the real competitive alternatives from a customer’s perspective

- Value (and proof)

- Value is the benefit you can deliver to customers because of your unique attributes. In my earlier example of the database, the value that mapped to our patented algorithm was that companies could get answers from their data in minutes rather than hours, which helped them serve their customers better

- If unique attributes are your secret sauce, then value is the reason why someone might care about your secret sauce

- Value should be as fact-based as possible. Qualitative value claims, such as “people enjoy well-designed user interfaces,” are too subjective and customers won’t believe them. Your opinion of your value does not count as proof; the opinion of customers, reviewers and experts does. Data or third-party opinions are difficult to refute. Your value needs to be provable in an objective and demonstrable way

- Target market characteristics

- In most cases, the value you provide is at least somewhat relevant to a wide variety of customers. However, if you are a small business you don’t have an unlimited marketing budget and a giant army of salespeople. Your sales and marketing efforts have to be focused on the customers who are most likely to buy from you. Your positioning needs to clearly identify who those folks are. And simply put, they are the customers who care the most about the value your product delivers. You need to identify what sets these folks apart. What is it about these customers that makes them love your product more than others? How can we identify them?

- Your target market is the customers who buy quickly, rarely ask for discounts and tell their friends about your offerings

- Market category

- Think of the market category as a frame of reference for your target customers, which helps them understand your unique value. Market categories serve as a convenient shorthand that customers use to group similar products together

- Declaring that your product exists in a market category triggers a set of powerful assumptions

- Customers need a way to make sense of the overwhelming number of products on the market. When they are presented with a new product, they will attempt to use what they know to try to figure out what it’s all about. Market categories are one way that customers organize products in their minds. Declaring that your product exists in a certain market category will set off a powerful set of assumptions in customers’ minds about who your competitors are, what the functionality of the product should be and what the pricing is like

- For example, if I describe my product as “a customer relationship management (CRM) tool,” you will assume my competition is Salesforce, because they are the leader in that market. You would assume the features include basic CRM functionality such as keeping track of contacts, activities and opportunities. You would also naturally assume that my pricing is similar to Salesforce, both in the pricing model (a monthly price per user) and the actual cost

- Your market category can work for you or against you

- If you choose your category wisely, all the assumptions are working for you. You don’t have to tell customers who your competitors are. It’s assumed! You don’t have to list every feature, because it’s assumed that all products in the category have basic category functions

- However, a poor category choice can turn that power against a product. If the market category we select triggers assumptions that do not apply to our product, then a good portion of our marketing and sales efforts are going to be spent battling those assumptions

- Market categories help customers use what they know to figure out what they don’t

- A well-chosen market category will help make your unique value more obvious to your target customers

- (Bonus) Relevant trends

- Positioning a product within an established market category will help customers quickly understand your product and whether or not they should consider buying it. You should always make it easy for prospects to understand what market category you operate in. But there is another way to give your customers additional context to help them understand why your product is valuable. Used carefully, trends can help customers understand why your offering is something they need to pay attention to right now

- It’s easy to confuse market categories and trends, but they are not the same thing. Market categories are a collection of products with similar characteristics. Trends are more like a characteristic itself, but one that happens to be very new and noteworthy at a given point in time

- Market categories help customers understand what your offering is all about and why they should care. Trends help buyers understand why this product is important to them right now. Trends can help business buyers understand how a product aligns with overall company priorities, making it a more strategic and urgent purchase. Trends are important because, as customers, we want to learn about new, interesting and potentially disruptive technologies or approaches. Nobody wants to be left behind when a shift happens, so we’re constantly looking out for new developments that might have an impact on us and our business

- Using a trend in positioning is optional (but often desirable)

- Position your product in a market category that puts your offering’s strengths in their best context, and then look for relevant trends in your industry that can help customers understand why they should consider this product right now

-

Each component has a relationship to the others

-

Attributes of your product are only “unique” when compared with competitive alternatives. Those attributes drive the value, which determines who the best target customers are, which in turn highlights which market frame of reference is the best one to highlight your value. Trends must be relevant to your target customers, and can be used in combination with your market category to make your product more relevant to your buyers right now

- Because these relationships flow from one another, the order in which you define the components is very important. I’ve seen teams start with defining key features, without looking at competitive alternatives, and the resulting positioning doesn’t connect with how customers really evaluate a solution. Similarly, I’ve seen teams start with value or a segmentation and end up with positioning that doesn’t click with customers. In the work I’ve done with startups, I’ve determined that it’s critical to start with understanding what the customer sees as a competitive alternative, and then working through the rest of the components—attributes, value, characteristics, market category, relevant trends—from there

Here are the 10 steps to position your product

- STEP 1. Understand the Customers Who Love Your Product

- Your best-fit customers hold the key to understanding what your product is

- Looking back at the first few times I repositioned a product, I kept coming back to our happiest customers and how they thought about us. In one case, we tried to survey all of our customers to see why they loved us, and the results were muddy. There didn’t seem to be any patterns in why people picked us. I wondered if the results would look different if I only surveyed the ecstatic fans and left the moderately happy customers out of it. Suddenly a clear pattern emerged: all of our customers could look like these very happy ones if we focused our marketing and sales efforts on companies with characteristics similar to the ecstatic fans

- The first step in the positioning exercise is to make a short list of your best customers

- They understood your product quickly and bought from you quickly. They became raving fans, referred you to other companies and acted as a reference for you. They represent the perfect type of customer you want to buy from you (at least in the short term). Make a list of them. You will use this list as a reference point for the rest of the exercise What if I don’t have any super-happy customers yet?

- This positioning process assumes you have enough happy customers to see a pattern in who loves your product and why. Until you can see that, you will want to hold off on tightening up your positioning

- Time for a test. In the early days of a company, when you are still learning about what customers love and hate about your offering, you need to get your product in front of a fairly wide set of potential customers. Test your offering on this diverse audience so you can see patterns emerge. Do bigger businesses love your product more than smaller ones? Are businesses in a certain industry more drawn to your product than those in other industries? Are your happiest customers more likely to have certain characteristics? We can guess who loves our product most and why, but frequently our guesses are incorrect. Until we have more experience with real customers, it’s better to keep our minds open and our positioning loose, and see what happens

- Think of your product as a fishing net. You have a theory that your net is good for catching grouper, but you haven’t fished with it yet so you aren’t certain what you might catch. At first, you’ll want to go where there are lots of different fish and see what you pull up. If you notice over time you’re pulling in a lot of tuna, not grouper, you can move to the tuna spot and do the same amount of work to get a lot more fish. If you had positioned your tuna net as a grouper net in the beginning, you might never have figured out your best positioning. Positioning your net broadly as a “fish net” when you have little market experience is the best way to keep your options open until you have enough customer experience to start seeing patterns

- Customer-facing positioning must be centered on a customer frame of reference

- STEP 2. Form a Positioning Team

- A positioning process works best when it’s a team effort, ideally from across different functions within the company. Each team, from sales to marketing to customer success, can bring a unique point of view relative to how customers perceive and experience the product

- Who should be there?

- The person responsible for the business of that particular product must be in the room and be seen as driving the positioning effort. Positioning is a business strategy exercise—the person who owns the business strategy needs to fully support the positioning, or it’s unlikely to be adopted. In startups, the head is the CEO and/or the founders. In larger companies, the head is usually the division or business unit leader and occasionally the head of marketing or head of product

- A positioning exercise that is not a team effort driven by the business leader will fail

- Positioning impacts every group in the organization. Consider these outputs that all flow from positioning:

- Marketing: messaging, audience targeting and campaign development

- Sales and business development: target customer segmentation and account strategy

- Customer success: onboarding and account expansion strategy

- Product and development: roadmaps and prioritization

- Positioning is intertwined with the overall business strategy and therefore needs to be led by the business leader. Because positioning impacts the overall team in significant ways, the leaders of each business function must also agree with and execute the positioning, so they should be involved in developing it. You will also want each group represented because they often hold very different perspectives on competitive alternatives, unique features and the characteristics of a best-fit customer. Marketing, sales and customer success interact with customers at very different points in the buyer journey. Product development may have less direct interaction with customers than other folks in the room, but they will have an important perspective on competitive differentiators and what is and is not possible to do with the product

- STEP 3. Align Your Positioning Vocabulary and Let Go of Your Positioning Baggage

- In order to consider possible new ways to think about a product, we have to consciously set aside our old ways of thinking about it. To do that, we need a common positioning vocabulary

- In the workshops I run, I set aside the first hour to go over positioning concepts and definitions with the team. At a minimum, the team needs to be on the same page regarding:

- What positioning means and why it is important

- Which components make up a position and how we define each of those

- How market maturity and competitive landscape impact the style of positioning you choose for a product

- Market confusion starts with our disconnect between understanding the product as product creators, and understanding the product as customers first perceive it

- The positioning team needs to understand the concept of “positioning baggage” before they can attempt to let go of it. You might find that each team member has a different level of positioning baggage—founders and long-time employees might view the product from the full perspective of its history, while newer employees do not

- Start by calling out where your history appears in your current positioning. Is your current market the one identified when you imagined the product? Do you use terminology and describe features in the same way as when you started? Being conscious of the presence of your history in your current position will help everyone be open to alternatives

- The most important part of this step is to get agreement from the team that, although the product was created with a certain market and audience in mind, it may no longer be best positioned that way. The team needs to agree to suspend their opinions about the positioning of the product for the duration of the exercise so they can be open to new ideas

- STEP 4. List Your True Competitive Alternatives

- Customers don’t always see competitors the same way we do, and their opinion is the only one that matters for positioning

- It’s natural for product creators to start by looking at the product and its features to determine the best market, and then build a context around that. As product people, it’s often the place where we feel most comfortable. After all, who knows more about our solution than us? But you need to look at those features from a customer’s point of view

- The features of our product and the value they provide are only unique, interesting and valuable when a customer perceives them in relation to alternatives

- Although every component of positioning is related to other components, the foundation is the problem your customers are trying to solve, and how they perceive your offering in comparison with other ways of solving the problem

- If problems are the root, why not start by asking customers what problems they’re trying to solve? Customers, although well-versed in their problems, are often terrible at describing them in a way that gives product creators enough nuance to make decisions. For example, at one startup I worked at, we asked customers what problem they were trying to solve by using our database product. Our users were generally database administrators, and their answers were typically quite specific and technical: “We just want to run a fast query” or “We have to produce a report, so we need to retrieve data from a very large database very quickly.” From those answers, I could assume they viewed our database as one that can quickly execute queries. But when we asked them what they would use if our database didn’t exist, none of them named another database; instead, they suggested business intelligence tools or data warehouses

- Understanding the customer’s problem wasn’t enough—to really understand how they perceived our strengths and weaknesses, we needed to understand the alternatives to which they compared us. Customers always group solutions in categories, but talking to them about problems doesn’t necessarily reveal those categories

- You need to create a position that highlights the unique strengths of your product as customers perceive them. To do that, you need to understand who your real competitors are in the minds of customers. Many companies have weak positioning precisely because they don’t clearly understand their true competitive alternatives in the minds of customers

- Understand what a customer might replace you with in order to understand how they categorize your solution

- The best way to understand competitive alternatives is to answer the question, What would our best customers do if we didn’t exist? The answer could be that they would use another product that looks like a direct competitor with you. But often that’s not the case. For many new products, the answer is “use a pen and paper” or “hire an intern to do it.” Some of the startups I work with have ideas so innovative that customers don’t even understand that they have a problem—if the product didn’t exist, they would simply “do nothing.”

- When I go through this exercise in workshops, teams will often want to create an exhaustive list of every possible alternative. That’s fine, but I encourage the team to (1) remain focused on the best-fit customer list and name only what those customers would see as an alternative, and (2) rank the list from most common to least common. This way, the team focuses on the most common alternatives and won’t worry as much about rare ones

- The competitive alternatives often naturally cluster, and if so, it’s helpful to group them. For example, there might be a group called “do it manually” that includes “hire an intern” and “do it myself with Excel” and another group called “use a small-business accounting solution” that includes QuickBooks, FreshBooks, etcetera. Grouping the alternatives helps the team move to the next step. In my experience, teams usually end up with a minimum of two and a maximum of five groups of alternatives

STEP 5. Isolate Your Unique Attributes or Features

- Strong positioning is centered on what a product does best. Once you have a list of competitive alternatives, the next step is to isolate what makes you different and better than those alternatives

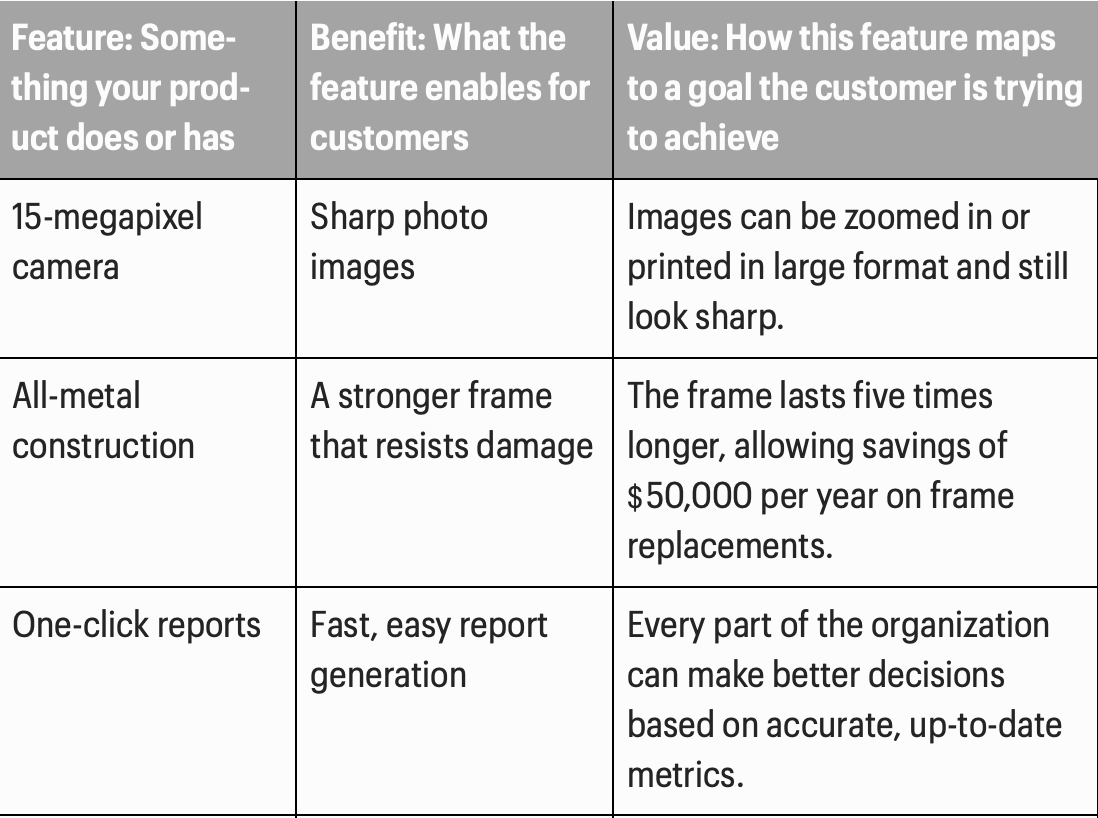

- In this step you need to stay focused on features and capabilities (also called attributes), rather than the value that those features drive for customers (we will get to that in Step 6). I define features as something your product or company has or does. Some examples of features: “a 15-megapixel camera,” “integrates with QuickBooks,” “one-click installation” and “metal construction.”

- In this step, list all of the capabilities you have that the alternatives do not

- List every attribute you can think of, even if it seems like it could be a negative to certain customers and even if you’re uncertain what its value might be. For tech companies, patented features are an obvious place to start. Sometimes it is helpful to think about the feedback you get from customers when you ask them why they chose your offering. You might be the only consulting business with a certain combination of skills and experience. You might be the only company with a certain technology or a certain set of partnerships. You might be the only hat maker that sources materials from Canada or the only makeup that is made from herbs grown in your own organic garden

- Your opinion of your own strengths is irrelevant without proof

- Some groups at this stage will list features that are either difficult to prove or really more of a benefit than a feature. “We provide outstanding customer service” is probably the most common of these, followed by “very easy to use.” Focus on the characteristics of your product or company that drives a potential benefit—ideally those features are based on objective facts and are provable. For example, I have yet to meet a company that believes they provide terrible customer service. If you truly believe that your company is better at customer service, how would you go about proving that? Do you have more support people than your competitors and can you prove it? Do your support people have certifications that others don’t? Ease of use is another “feature” that I believe is really a value. What is it about your product that makes it easier to use and how do you prove it? Do your competitors’ products require training and your product doesn’t? Can you quantify how long it takes to become proficient with your product versus alternative products?

- Third-party validation that your product’s feature is better than the alternative counts as proof. If an independent reviewer or analyst stated that your product is easier to use, that’s a fact. If a customer says in an approved quote that your customer service is much better than another company’s, that’s proof

- Concentrate on “consideration” rather than “retention” attributes

- Consideration attributes are things that customers care about when they are evaluating whether or not to make a purchase. Every product has features that you can connect directly to a goal the customer would like to accomplish right now. Retention attributes are features that aren’t as important when a customer is making an initial purchase decision, but are very important when it comes time to renew. These include how easy it is to do business with a company and the quality of customer support

-

List as many attributes as you like at this stage. You’ll group them as you move to the next stage in the process. Focus on capturing the broader set without trying to decide what’s really important and what isn’t

- STEP 6. Map the Attributes to Value “Themes”

- Attributes or features are a starting point, but what customers care about is what those features can do for them

- Attributes like “15-megapixel camera” or “all-metal construction” enable benefits for customers such as “sharper images” or “a stronger frame.” Articulating value takes the benefits one step further: putting benefits into the context of a goal the customer is trying to achieve

- Value could be “photos that are sharp even when printed or zoomed in,” “a frame that saves you money on replacements,” “every level of the organization knows the status of key metrics” or “help is immediately available across every time zone.”

- Features enable benefits, which can be translated into value in unique customer terms

- In this step, you’ll capture the value that each of your unique attributes enables for customers. Each feature can have multiple value points, and a combination of features can provide value as well. In Step 7, we’ll determine which customers find these valuable and how many of those customers there might be

- In your list, you should see a handful of themes start to emerge and the value those features deliver to customers. Now we need to organize the list

- To group points of value, you need to take the perspective of a customer. What points would naturally be related in the minds of your customers and prospects? For example, if you have attributes like “works on any mobile device” or “works without an internet connection,” those might both provide value to customers who would like to use the solution with field workers in remote locations or locations with intermittent Wi-Fi or cell access. You could clump those attributes in a group called “supports remote environments.”

- Group attributes that provide similar value so you can get down to a more reasonable number. The goal of this step is to see the patterns and shorten the list to one to four value clusters. It’s not uncommon for this exercise to produce just a single value point

- Remember: this positioning exercise is not about highlighting every little feature and attribute that our customers love

-

In positioning a product, we’re taking the most critical things that make us special and worth considering, and bringing the resulting unique value to the front and center

- STEP 7. Determine Who Cares a Lot

- Once you have a good understanding of the value that your product delivers versus other alternatives, you can look at which customers really care a lot about that value

- It’s important to remember that although you have unique attributes that deliver value to customers, not all customers care about that value in exactly the same way. You might have a solution for invoicing that supports integration with an accounting package like QuickBooks. This feature provides the value of saving time and reducing errors from manually entering data. For customers who don’t use QuickBooks, the value is irrelevant. Among those who do, customers who send a large number of invoices will feel the pain of data entry more than customers who send only one or two invoices a day. The customers who send a lot of invoices will care a lot about the value of reducing time and errors

- Marketers call this step a “segmentation” exercise

- An actionable segmentation captures a list of a person’s or company’s easily identifiable characteristics that make them really care about what you do. For consumers, a segmentation could include combinations of things such as other brands they own or like, stores they buy from, the job they hold or their music or entertainment preferences. For businesses, it could be the way they sell, other products they have invested in or the skills they have or don’t have inside their company

- A segment can be defined by narrowing the set of buyers you are targeting. For example, you might focus the category of “accounting software” to “accounting software for freelancers or lawyers.” You might narrow down “sporting goods” to “sporting goods for babies” or “for dogs” or “for octogenarians.” In general, the segment needs to meet at least two criteria to be worthy of focus: (1) it needs to be big enough that it’s possible to meet the goals of your business, and (2) it needs to have important, specific, unmet needs that are common to the segment. If you’re a tennis racquet maker and decide to market a racquet for seniors, you need to figure out first if there are enough tennis-playing seniors who might need a racquet, and second if you could fulfil an unmet need that seniors have in their racquets

- Best-fit customers are easiest to sell to and retain

- Focusing on a best-fit prospect segment doesn’t always make sense to people who don’t have a marketing background. If I wanted to increase my chances of landing a customer, wouldn’t I want to target as broad a market as possible? The reality is the exact opposite. The broader your focus, the more difficult it is to connect with prospects and convince them that your solution is the best one for them above all others

- Target as narrowly as you can to meet your near-term sales objectives. You can broaden the targets later

- I encourage teams not to get their positioning too far ahead of their business objectives. Think about your sales targets for this year and how many sales you need to make to achieve them. Could you hit your targets by focusing on only your best-fit customers? If the answer is no, you need to broaden your definition of “best-fit.” If the answer is yes, keeping your positioning focused on that segment is the most efficient use of your sales resources and the fastest and easiest path to hitting your sales targets

- Keep in mind that your product positioning will constantly be evolving. There is no need to make sure that your positioning will fit perfectly with where you or your product will be in ten years or five years or even two years from now. Similarly, your target customers will also evolve over time. Great positioning resonates with your best-fit customers right now, and will evolve with them over time

- STEP 8. Find a Market Frame of Reference That Puts Your Strengths at the Center and Determine How to Position in It

- You now have a good handle on your ideal prospects, your product’s unique attributes and the value those attributes can deliver. The next step is to pick a market frame of reference that makes your value obvious to the segments who care the most about that value

- Picking a market that does this is harder than you might think. Chances are, when you first conceived the offering, you had a market in mind. You were building an email system for lawyers, a bicycle that could give you directions, a robot that could move things around a manufacturing plant. Baked in was the idea of the market—“database,” “bicycle” and “robot” are all markets that exist and mean something to customers. However, since your offering evolved and the market itself evolved over time, the original market category may no longer be the best way to frame your unique strengths. Also, the customers most likely to buy your product might have a very different point of view on markets than you do

- In the context of this exercise, a “market” needs to be something that already exists in the minds of customers (except in the very rare case where you make a conscious decision to create a new market—which we’ll discuss later in this step). We position our offering in a market to trigger a set of assumptions—about competitors, features and pricing—that work to our advantage. By choosing to position within a specific market, you’re giving your prospects clues about what products they should compare you with, your key features, your price and your benefits. Those comparisons help customers quickly figure out what your product is all about and whether or not they should consider purchasing it

- In Step 3, you let go of your “default” market—part of your positioning baggage—which was most likely the place where you started. Now you are looking to deliberately choose a market frame of reference that makes your value obvious to the folks who care about it the most. There are a few ways to go about this:

- Use abductive reasoning. The adage “if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck” also applies to new products. With abductive reasoning, you choose a market category by isolating your key features and their value, and asking yourself, What types of products typically have those features? What category of products typically deliver that value?

- Examine adjacent (growing) markets. Another place to look for options is in the markets adjacent to the one in which you have been positioning yourself. Frequently, there are overlaps or blurry lines between markets. As a product shifts over time, its features and value could look more at home in a neighboring market. Especially in the tech space, it’s not unusual for lines between markets to shift or be redrawn as companies emerge, release new technology or come up with new ideas. Looking at adjacent markets is a good way to find markets that might make your value more obvious to prospects. Pay particular attention to adjacent markets that are growing quickly. Positioning yourself in a growing market has obvious benefits: a rising tide of customer interest, media focus and buzz, and the appearance of being new and cool—who doesn’t want that? But be careful—simply wanting to belong in a market doesn’t make it the right one for you. Only choose a market if it makes your strengths obvious

- Ask your customers (but be cautious). I’ve had folks ask me, “Can’t you just ask your customers what market you’re in?” My answer: “Sometimes.” If you have already positioned yourself in a given market, your customers will have at least attempted to place you there, even if that attempt confused them. They will naturally try to put you in markets that are close to that market. That was the case with our database—a customer described us as an analytics tool because he had been looking at analytics tools and was familiar with them. This market was closely associated with the database market and therefore it wasn’t much of a leap for him to think of us that way

- I would caution you to be extremely careful in seeking feedback from customers and prospects about what market they see you in. Prospects may see things differently than those who have already tried to make sense of your product one way and failed. Also, customers will only try to position you in markets that are frequently linked to their industry or job function. Customers aren’t positioning experts, nor are they experts in how a market category works. Frequently they will attempt to position you in the most obvious market possible, and this market is often not the best one for highlighting your strengths

- There are different approaches for isolating, targeting and winning a market—and certain styles work better for some than others

- Picking a market is like giving customers an answer to the question, What are you? Frequently, however, we need to think a little bit deeper about how we intend to win in the market we have chosen. At a high level we can either choose to enter an existing market or create a new market. If we choose to enter an existing market, we can either compete to win the entire market or position our product to win a slice of it. The “style” of positioning you choose will depend on a set of factors including the competitive landscape and your business goals. Here’s my advice on how and when to use each of them:

- Head to Head: Positioning to win an existing market You are aiming to be the leader in a market category that already exists in the minds of customers. If there is an established leader, your goal is to beat them at their own game by convincing customers that you are the best at delivering the solution

- Big Fish, Small Pond: Positioning to win a subsegment of an existing market You are aiming to dominate a piece of an existing market category. Your goal is not to take on the overall market leaders directly, but to win in a well-defined segment of the market. You do this by targeting buyers in a subsegment of the broader market who have different requirements that are not being met by the current overall market leader

- Create a New Game: Positioning to win a market you create You are aiming to create a new market category. Your goals are first to prove to customers that a new market category deserves to exist, then to define the parameters of that market in the minds of customers, and lastly, to position yourself as the leader within it

- When to use the Head to Head style

- If you are already the leader in the market, the status quo suits you. The way prospects define the market has worked well for you (you are the leader here after all!), and you would like them to continue to define it that way. Similarly, the way they currently make decisions about what to buy seems to your advantage. Prospects are comparing alternatives using a set of features where you come out on top

- If you are launching a new product, particularly if you are a small business just starting out, the Head to Head style is rarely a good choice. Trying to beat an established market leader at their own game is a bit like trying to out-cola Coke. It would be foolish for a small company to ever try

- A larger company might attempt to take on an established leader head to head, but only where the market sands are shifting in a way that could put the leader at a disadvantage or a challenger at an advantage. A new breakthrough capability, a change in government regulations or a shift in economic factors might give a strong challenger the opportunity they need to take down an established leader. Without a clear competitive advantage, however, even a large company will have to be prepared to fight hard for every win and cross their fingers for the leader to make a mistake

- The only case where a company might want to position a new product in a known category is when the category itself is defined and understood by buyers, but a strong leader has not yet been established. In technology we see this in new and emerging market categories. For example, “smart glasses” for consumers have been on the market for years and many people understand the basic functionality of smart glasses as being a sort of wearable display and/or camera. Some folks can name a handful of vendors that sell them (Epson or North might come to mind), but most people would be hard-pressed to name a “leader” in this market. In this case, North doesn’t need to create an entirely new category from scratch (although it certainly has the opportunity to shape the details of what customers expect from products within it), and it can position itself to be the leader of the entire market, since no clear leader exists yet

- The advantage of positioning in an existing market category is that you don’t have to convince people the category needs to exist

- You also benefit from the assumptions that the category brings to mind for prospects. The bonus is you get all of that without having to fight directly with an established leader

- Take note of your competition. Sure, you’ve managed to pick a market that doesn’t already have a strong leader that you have to take on, but that doesn’t mean you are alone here. The fact that buyers understand what the market is all about means that there is market demand, and though the market feels uncrowded at the moment, it won’t stay that way for long. If you choose to enter this market, you will have to commit to moving quickly to establish yourself as the leader before someone else does. For technology companies, this often means committing to growing your customer base as quickly as you can, which can require outside funding (and the risks and potential headaches that come with that)

- If you are already the market leader, you need to continually reinforce to your buyers that the current way of thinking about the market is the best one. This work includes reinforcing the current buying criteria and reiterating why you are the best to deliver those things. You need to quickly and forcefully defend against competitors who attempt to convince buyers to pay attention to other, emerging criteria. You also need to continually demonstrate why you deliver on these criteria better than anyone else in the market

- If you are fighting to unseat a leader in an existing category using the currently established criteria, you’re in a battle to prove that you can beat the leader at their own game. You have to clearly demonstrate to the market that you have a superior ability to deliver, and you need to support that claim with hard evidence and undeniable facts

- Be prepared to battle against multiple competitors who will be simultaneously trying to prove they are better than you are at the currently established buying criteria, as well as others who are trying to redefine the purchase criteria to their advantage

- Positioning Story: My startup transforms our crummy database into a kickass data warehouse. In Part I, I outlined how my company repositioned its main offering from a “database” to a “data warehouse.” Let’s examine that positioning shift through the lens of the Head to Head style. When the company was formed, we thought of our product as a database, so we positioned it as a database. The market category of database, however, was very well established with a clear market leader (Oracle) and a clear set of expected features and pricing. Unknowingly, by calling ourselves a “database” we were announcing to the world that we had the intention of beating Oracle in the overall database market. It shouldn’t have been a surprise that the first question we got from every prospect was, So how are you better than Oracle? The expectation was that we sold a database just like Oracle’s database, so if we were getting into this business we should have everything their database had, only better. We obviously didn’t have that! While we believed we were better at Oracle for certain uses for certain buyers, we clearly weren’t a better general-purpose database than Oracle. As a startup, we could not credibly compete in this market, let alone win it. Later, we focused on our real competitive differentiator, which was our patented way of doing analysis on a large amount of data. Thinking about our ability to do analytics led us to reposition ourselves as a data warehouse—a completely different market from databases. The data warehousing market at the time was established and most larger companies understood what a warehouse was. Few of them bought warehouses, however; many companies were still developing them in-house because few commercial warehouses existed. For us, this was good news: the demand and market existed but a clear leader did not. This shift in positioning immediately got us away from trying to compete with Oracle, and it aligned with our strengths. It also had the side benefit of allowing us to raise our prices. Databases at the time were a commodity, but a data warehouse—with fewer options on the market—commanded premium pricing

- Big Fish, Small Pond: Positioning to win a subsegment of an existing market

- If a market category already exists and there is an existing leader, does that mean you can’t compete in that category? Of course not! You may not be able to compete with an established leader head on, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a way for you to get a foothold in a piece of the market. Once you do, you can keep expanding your patch until you’re established enough to take on a large category leader

- Many startups compete in established market categories and do so successfully by first breaking up the market into smaller pieces and focusing on one piece they can win. In marketing, the process of splitting up an existing market is called subsegmenting. A market can be subsegmented by industry (manufacturing vs. retail), by geographic region (North America vs. South America), company size and a myriad of other criteria

- The goal of the Big Fish, Small Pond style of positioning is to carve off a piece of the market where the rules are a little bit different—just enough to give your product an edge over the category leader

- Like the Head to Head style of positioning, here you are leveraging what buyers already know about the broader market category, but you are calling attention to the fact that some of the requirements for your chosen subsegments are different and not being met by the overall category leader

- You get the advantage of a well-defined category without the stiff competition

- In Head to Head you are attempting to beat Coke in the cola market; in Big Fish, Small Pond, you’re selling Coke for dogs. While your product is a lot like Coke (brown and fizzy), it does something that Coke doesn’t do and that dogs really, really want (it tastes like bones)

- You are not trying to change the purchase criteria for the overall category; in fact, you will have to prove that you do a “good enough” job in those areas when compared with the category leaders. Your focus is showing that there is a subsegment of the overall category with a specific set of needs that the current category leaders are not addressing. Those needs are very important—so important that buyers may want to relax a bit on the overall category criteria to make sure that their subsegment needs are met

- Dominating a small piece of the market is generally much easier than attempting to directly take on a larger leader.

- From a marketing and sales perspective, smaller subsegments are easier to reach and target, and gaining traction in a market that is more homogeneous is generally easier. List building is easier when you are targeting a subsegment, as is getting in front of groups of prospects. Your value proposition can be highly targeted to these prospects and you will generally have an easier time making your solution’s distinct advantages obvious to prospects

- In my experience, one of the best advantages of this style is that once you begin to get traction with some customers, your advantage in the subsegment tends to accelerate quickly. For example, if you are targeting law offices or banks, success with even a single customer is directly applicable to the next customer and can help move the next deal along quickly. Communities also tend to cluster and share information with each other. As you close more business in a particular subsegment, knowledge of your solution in the community will grow quickly because of the links between people in the segment

- Word-of-mouth marketing happens most naturally in tight market subsegments

- A caution here is that the subsegment must represent a large enough opportunity that you can meet your business goals, at least in the short term. Companies tend to shy away from this style because they are worried that moving from targeting the entire market to just a small piece of it will mean less opportunity. In reality the opposite is frequently true: you are simply unselecting the part of the market that was never going to buy your product anyway in order to focus only on customers where you have a distinct advantage. The best way to determine if your chosen subsegment is big enough is to determine how many sales you need to make in the next year to meet your revenue goals. If you need to close thirty deals to make your number this year and your target segment has only one hundred businesses in it, you are going to have to look elsewhere. If, on the other hand, you need to close thirty deals and there are thousands of businesses in your subsegment, it’s likely big enough for now

- Just because your initial target market is narrow doesn’t mean you will stay narrowly focused forever

- Think back to the lessons in Step 7, about defining a subsegment of best-fit customers for now, and expand that group as the segment and the market evolve. You might start out targeting a very narrow segment but once you have enough customers there, you can start going after adjacent markets where the success you have built so far is relevant. For example, you could start out focusing on credit unions, then expand to retail banks more broadly and then on to other industries like insurance. Once you are larger, you may be ready to take on the market leader head to head, or try to create a new market (more on this in the third style of positioning, Create a New Game)

- When to use the Big Fish, Small Pond style

- First, this style requires that the category is well defined and there’s a clear market leader—and you’re not it. People must understand what you mean when you talk about the category. We all know what a vacuum cleaner or a car or bubble gum is, and we understand the basic buying criteria in these categories: vacuum cleaners should have good suction, cars should be reliable, bubble gum should be chewy and capable of blowing great bubbles. If the category is not well understood, subsegmenting it is only going to result in further market confusion

- Second, there needs to be clearly definable groups of customers with unique needs that are not addressed by the market leader. These subsegments may be buyers in a particular industry (banking or legal) or geography (Germany, Latin America), or they may have particular preferences (folks on a gluten-free diet, developers who are certified on Microsoft tools) or ecosystem characteristics (Mac users, marketers who use Eloqua, folks with low internet speed)

- The subsegment needs to be easily identifiable—meaning if I had to create a list of prospective buyers, I could figure out a way to do that. For example, I can easily make a list of companies that have more than 1,000 employees by searching the internet for company size info, or a list of Pokémon fans by looking at active users on fan sites or email groups. I would have a much more difficult time creating a list of companies that value design or happy people

- Last, it has to be possible to demonstrate that this subsegment has a very specific and important unmet need. For example, you might be appealing to companies with workers in very remote places who can’t use a solution that requires internet access, or banks in Europe that operate under a different regulatory environment and therefore have different privacy requirements than banks in the United States

- The need of the subsegment must be clearly identifiable, but even when it is, your ability to meet it must be strong enough to convince buyers to go with you over the safer choice of the market leader. These buyers were getting along for the most part by buying a solution that didn’t do everything but was likely “good enough” for their business. Convincing them to switch will require showing them that you have deeply understood their specific pain and have fully solved the problem

- The work of Big Fish, Small Pond

- This positioning style is often useful for smaller startups that are looking for a way to establish themselves in a market with a strong market leader that they can’t take on directly. The work of this style is first to educate the targeted subsegment about how a general-purpose solution is not meeting their needs. You need proof points that show there is a clear gap in value between the general-purpose solution offered by the market leader and your more-purpose-built solution. You need to help the subsegment understand what’s in it for them if they do have those needs met. There should ideally be a way to quantify the value to them if they choose your solution over the market leader’s more generic solution

- You also have to show that you meet or exceed the existing category criteria (at least the ones that matter most to your subsegment). Remember that you aren’t redefining the category, you are merely trying to capture a piece of it, so while you are leading with your defining features and value for your subsegment, you still have to prove that you meet the underlying basic needs common to the overall market category

- If you choose to use the Big Fish, Small Pond style…

- Understand that the subsegment must have truly distinct needs not being met by the leader in the broader market. If you are trying to dominate a subsegment, be careful that the market leader doesn’t turn their attention to the subsegment and try to offer a “good enough” solution with some features that at least partially meet the buyers’ needs. Large category leaders will often acquire small companies to block a fast-growing competitor from gaining on them in a particular subsegment. Ideally your competitive advantage is something that is difficult for the market leader to copy, either because you own the intellectual property, or (more commonly) because trying to match your functionality might cause them damage in the broader market where they are winning. It would be difficult for Coke to make a product aimed at dogs without suffering some damage to the perception of the brand among humans

- Create a New Game: Positioning to win a market you create

- Sometimes new technology or circumstances pave the way for a completely new market. Other times a market can be created by combining one or more existing markets to form one with different buying criteria. Developing a new market comes with its own distinct set of opportunities and challenges

- When to use the Create a New Game style

- Because this style of positioning is so difficult, it should only be used when you have evaluated every possible existing market category and concluded that you cannot position your offering there, because doing so would fail to put the focus on your true differentiators and value. This style can also work if your company is large and powerful enough to capture the attention of customers, media and analysts to make a case for why the new market category deserves to exist

- You aren’t simply capturing demand that already exists; you have to spark some demand first.

- This style is usually only possible when there has been a massive change with a big potential impact on what is possible or what is important in a market. These changes can include new technologies, economic changes, political forces or a combination of these. We saw new markets emerge as cellular networks increased their speeds and coverage, making it possible to do things on a smartphone we couldn’t before. Government regulations in privacy and security, particularly in banking and insurance, have driven a wave of data security and customer-tracking software innovation over the past two decades. Our shifting attitudes about privacy and community facilitated the rise of open social networks like Facebook and Twitter, and the backlash against the unintended consequences of heavy use of those platforms has, in turn, begun to transform our attitudes and preferences around privacy and security

- Often a category emerges when an enabling technology, a shift in customer preferences and a supporting ecosystem manage to come together at once

- If your product cannot be well positioned in any existing category, this might be a good option for you. If your solution requires both a new way of thinking about the boundaries of an existing category and a new way of thinking about purchase criteria, then it probably makes more sense to create an entirely new category rather than attempt to stretch existing categories along more than one dimension

- The work of Create a New Game

- Creating a new category is the most difficult style of positioning, even when the pre-existing conditions are aligned to support it, mainly because it involves the greatest amount of “teaching” the customer. In the other positioning styles, you’re leveraging what folks already know about a category and building on that to create a position in the mind of customers. In this style, you are starting with a blank canvas

- Customers need to first understand why the category deserves to exist. Why is the problem unique? Why do existing solutions in other categories fall short of solving that problem? While you are convincing the market that this category should exist, you are also teaching folks how to best evaluate solutions in that category. And while you are busy with all of that, you need to teach people why you are unquestionably the best vendor to deliver solutions in this category

- To credibly create a new category, you need a product that is demonstrably, inarguably new and different from what exists in other market categories

- Wishful thinking won’t convince prospects that you don’t belong in any other existing category—this needs to be obviously true in the minds of customers. Also, be aware that the leaders of existing categories may claim that your new product is merely a feature or subset of their existing solutions. To successfully create a new category, you need to have strong arguments against any competitor that tries to convince customers that what you are selling is “merely a feature” instead of a product in its own right

- Timing is also important in creating a new category. To help customers make sense of why this category hasn’t emerged sooner, there should be a very strong answer to the questions, Why now? What factors have finally made this category possible and/or necessary? These might be new technology capabilities, a shift in buyer behavior, a change in the business environment such as new government regulations or a shift in the economy

- Category creation is about selling the market on the problem first, rather than on your solution

- If the category doesn’t already exist, it means customers aren’t currently aware that they have a problem. They don’t understand the cost of not solving that problem, nor do they understand the potential value they can unlock by solving that problem. Customers need to be aware of those things before you can successfully convince them to purchase any solution (including yours)

- This style is very, very difficult to execute, but if you manage to pull it off, the rewards are massive

- Unlike the other positioning styles, Create a New Game allows you to create a market that is perfectly tailored to your strengths and weaknesses. It allows you to set the boundaries of the market exactly where you want them and to define purchase criteria so they map exactly to the things you do best. Anyone who successfully defines a market can become its leader because the market was specifically designed that way. Once the market is created, it takes serious work to change it in the minds of customers. Companies that successfully create a category in the customers’ minds are well set up to lead it, not only in the short term but also in the future

- This style is the most difficult because it involves dramatically shifting the way customers think, and shifting customer thinking takes a very strong, consistent, long-term effort. That means you need a certain amount of money and time to convince the market to make this shift. Because of the investment and time required, this style is generally best used by more established companies with massive resources to put toward educating the market and establishing a leadership position. For smaller companies, this style generally requires the participation of deep-pocketed, patient investors

- If you choose to use the Create a New Game style…

- Follow a long-term plan. At every step, you need to defend yourself as the category leader, or risk having a competitor with more resources and name-brand recognition reap the rewards of your hard work in creating the category. The most common way startups fail at this style is by working to build the market and then losing out on establishing themselves as its leader. At the exact moment when prospects start to show signs of understanding the category, a larger competitor or a well-funded fast follower swoops in to take advantage of their category-creation work and steal leadership from them

- Picking a market is like giving customers an answer to the question, What are you? Frequently, however, we need to think a little bit deeper about how we intend to win in the market we have chosen. At a high level we can either choose to enter an existing market or create a new market. If we choose to enter an existing market, we can either compete to win the entire market or position our product to win a slice of it. The “style” of positioning you choose will depend on a set of factors including the competitive landscape and your business goals. Here’s my advice on how and when to use each of them:

- STEP 9. Layer On a Trend (but Be Careful)

- Once you have determined your market context, you can start to think about how you can layer a trend on top of your positioning to help potential customers understand why your offering is important to them right now. This step is optional but potentially really powerful—if you go about it carefully

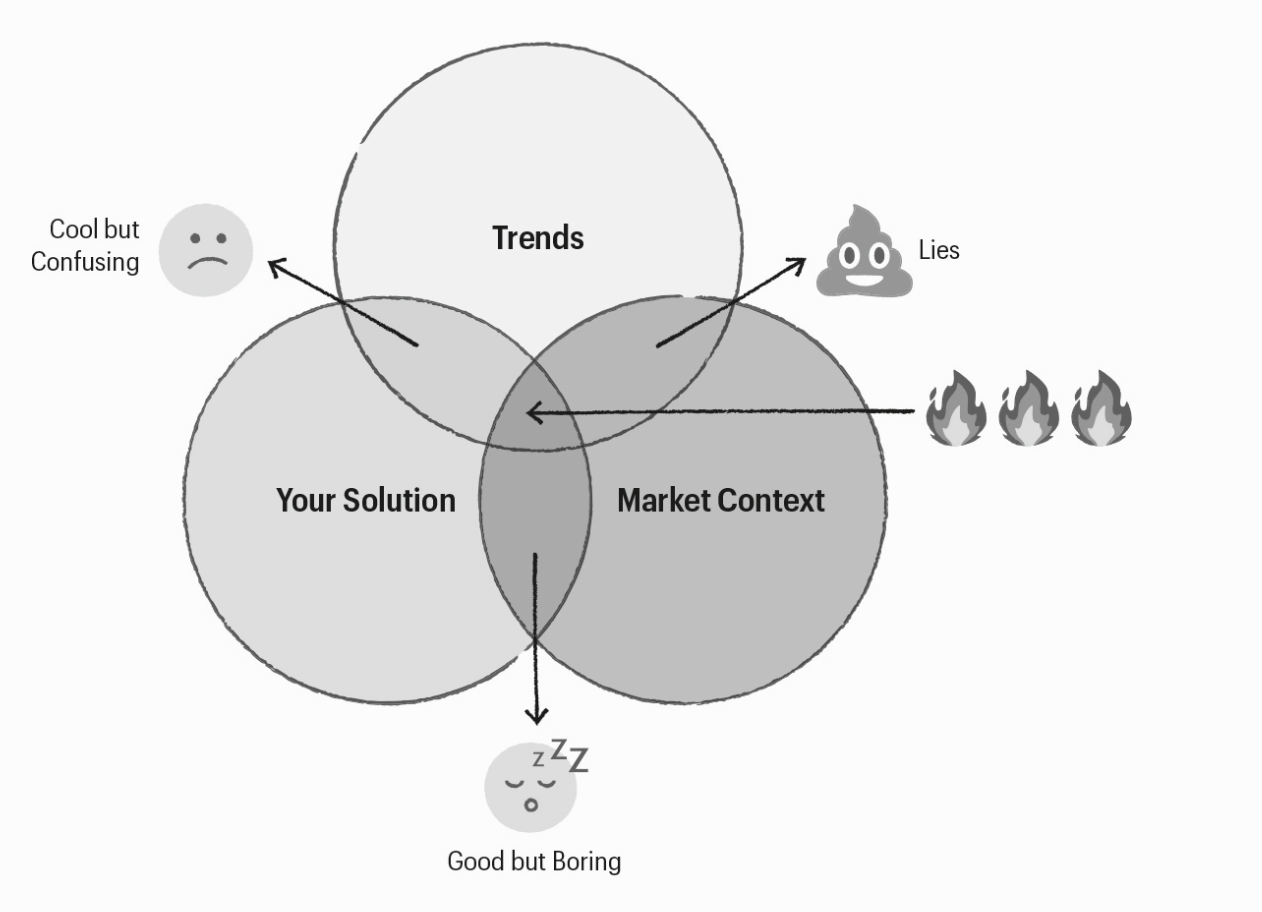

- Think of your product’s strengths, your market context and a trend that is relevant to your customer base as three overlapping circles. You are aiming for the center, where all three intersect

- At one point, I worked at a startup that sold a product for retail sales associates that gave them access to information across both e-commerce and in-store systems. The product was positioned in the market as a solution that helped retail sales associates serve customers better. When we talked to retailers, one trend that everyone was interested in was “mobility”—every retailer believed they would need tablets for sales associates in every store in the near future, but they weren’t exactly sure how they were going to support that. We used this mobility trend as a jumping-off point to talk about our solution for sales associates, because access to information across multiple platforms and devices—including tablets—was an obvious way that retailers could use mobility to empower their sales associates

- Positioning Story: Redgate Software makes a boring but profitable market cool—and even more profitable. Redgate Software is based in Cambridge, UK. They’ve been in business since 1999 and are the leader in the database tools market—providing services including data monitoring, synchronization, data privacy and automation. They have over 800,000 users, which means your company is likely a Redgate customer. Redgate has dozens of products in the market and they wanted to do a better job of telling a story of how customers could see more value by using the products together. Although business was great, customers didn’t always see Redgate’s products as an urgent or strategic (or dare we say it, cool) purchase. For Redgate, a shift in market category didn’t really make sense—their category was well established and they were a leader in it. But that doesn’t mean they couldn’t spice it up a little by aligning what they do with industry trends. Redgate noticed that DevOps concepts (software development, or Dev, plus IT operations, or Ops) were gaining in popularity with the development teams they worked with, but it seemed that nobody was talking about the important role of databases in a DevOps transformation—particularly at a time when new data privacy regulations had customers concerned about data security and compliance. So they wove “database DevOps” into their positioning by creating content that described the importance of data in a DevOps transformation and by training their sales team on how to consult with more senior-level folks in a development team that were looking for ways to be smarter about implementing DevOps processes. The result was a dramatic increase in customers buying multiple Redgate products at a time and a whopping 100% increase in inbound leads (companies contacting Redgate wanting to buy their products)—a clear indicator that Redgate’s products had become a higher-priority purchase

- Describing a trend without declaring a market can make your product cool but baffling

- There are lots of ways that throwing trends into the mix can be potentially harmful. Companies can get too focused on the trend to the exclusion of the market, which ultimately leads to confused customers. It’s like describing why you are interesting without first telling people who you are. One example was a company that described its app to me as, “the sharing economy for pets.” I thought about my own dog and couldn’t imagine sharing him with anyone. When I told them I really didn’t understand what that was, they switched to describing themselves as “Uber for cats.” For a moment I thought about the possibility that these Silicon Valley engineers had succeeded in teaching cats how to drive. “Would they hit the brakes if a dog ran across the street?” I wondered. As enticing as Uber for cats was to me, it seemed unlikely that this was really what the product was all about either. After a bit of probing, they explained that their solution was a marketplace for pet services, like pet sitters and groomers, where customers could find, purchase and rate pet service providers. Once I understood what market they were in, it was much easier to understand what they did. In this case, “sharing economy” is not a market, it’s a trend. Uber is also not a market, it’s a company (and one that not everyone has consistent assumptions about)

- Trends can only be used when they have a clear link to your product. Start by making the connection between your product and the market obvious

- Another way that using trends can get you in trouble is if you focus on the trends and the market, but don’t show the link to your actual solution. One example of this is companies that get a little carried away with blogging and other forms of content creation—they are so busy writing content to attract readers that they forget there is an actual solution their company sells. While the trend might be fun to read about, it doesn’t help to sell any product

- When the company Long Island Iced Tea made the radical decision to change its name to Long Blockchain (really), it made headlines for days while investors and analysts tried to draw a link between their iced tea and this hot, new technology trend. The stock briefly soared as the company made little effort to explain how exactly it would exploit blockchain for its business, but that didn’t deter blockchain enthusiasts from speculating about all of the potential ways that an injection of blockchain magic might transform even a boring business that sold iced tea. Over the course of a couple weeks, however, it become clear that Long Blockchain didn’t have a blockchain strategy to go with the name change—no new partnerships, no explanation of how blockchain would be used and no clear relationship between their existing business and any potential new business related to blockchain. Once investors realized this disconnect, the stock plummeted and within months the company was delisted from the Nasdaq stock exchange, proving that trying to capitalize on hype without linking it to your product is a dangerous game

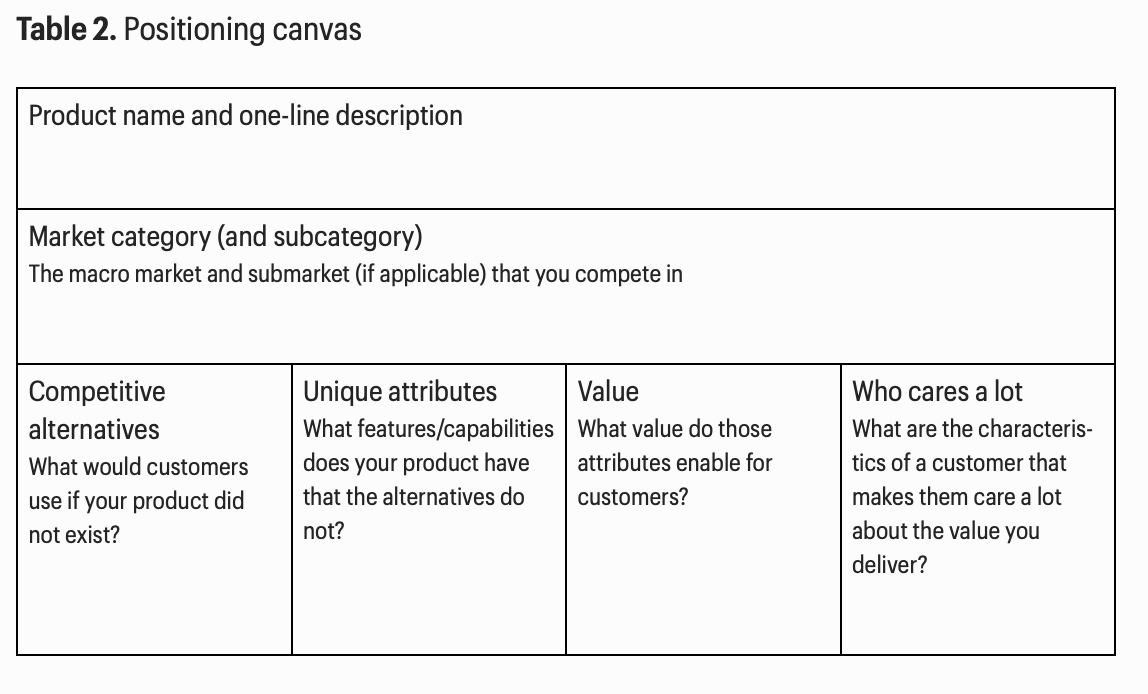

- STEP 10. Capture Your Positioning so It Can Be Shared