Understanding Michael Porter - Joan Magretta

Note: While reading a book whenever I come across something interesting, I highlight it on my Kindle. Later I turn those highlights into a blogpost. It is not a complete summary of the book. These are my notes which I intend to go back to later. Let’s start!

-

STRATEGY EXPLAINS how an organization, faced with competition, will achieve superior performance

-

The key to competitive success—for businesses and nonprofits alike—lies in an organization’s ability to create unique value

-

Creating value, not beating rivals, is at the heart of competition

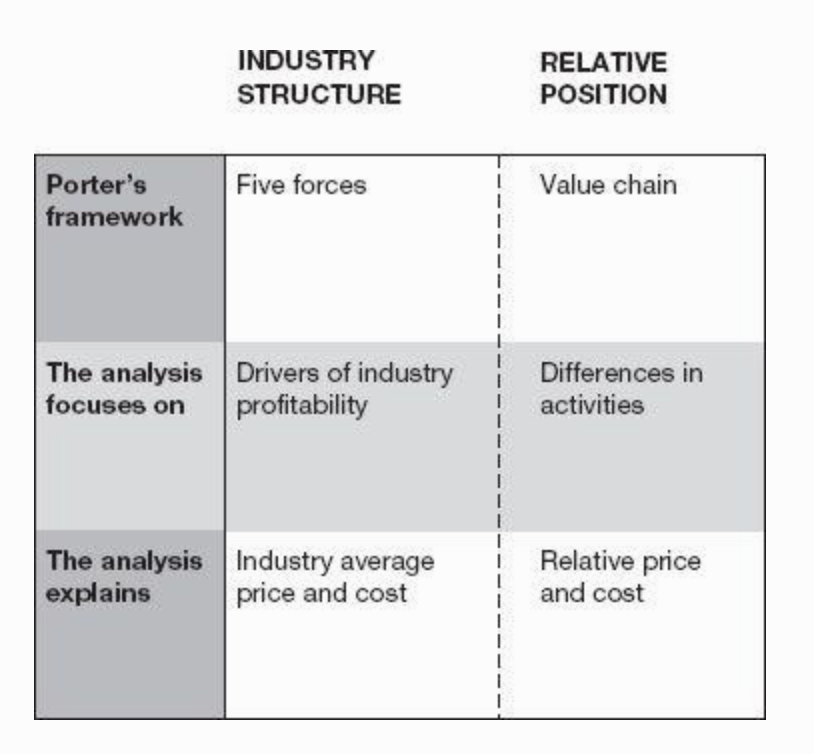

- Where does superior performance come from? Porter’s answer can be divided into two parts. The first part is attributable to the structure of the industry in which competition takes place

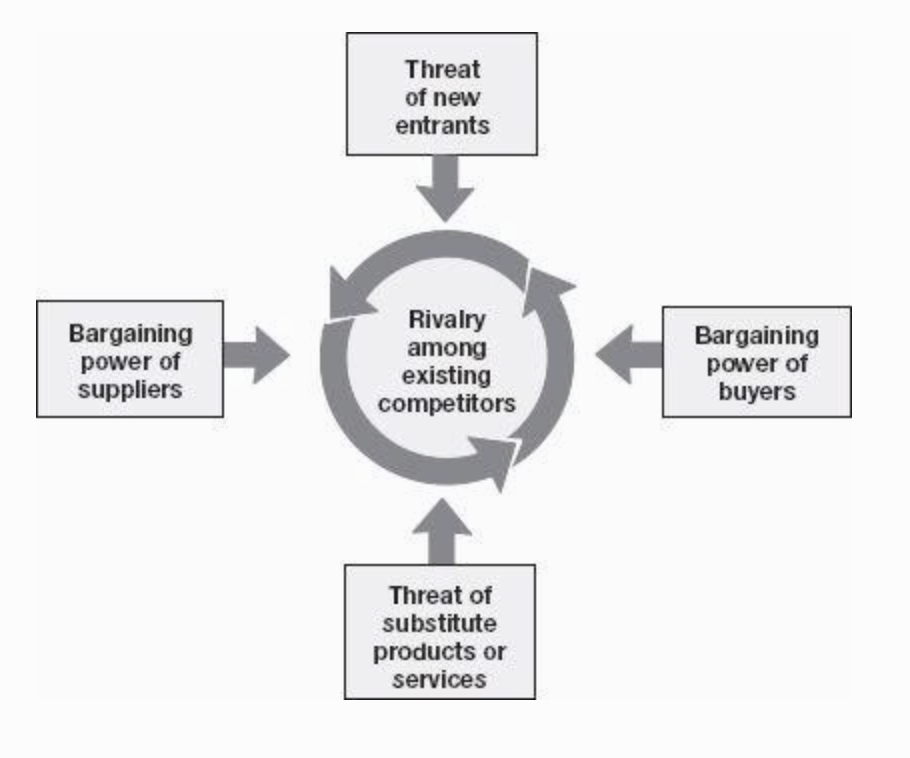

- Porter starts with the industry because competing to be unique is a choice made against a specific and relevant set of rivals, and because the structure of the industry determines how the value it creates is shared. Porter’s five forces framework explains industry structure and the profitability any company can expect simply by being “average.”

- The second part is attributable to the company’s relative position within its industry. Strategic positioning reflects choices a company makes about the kind of value it will create and how that value will be created. Here, competitive advantage and the value chain are the relevant frameworks

-

CEO Jack Welch say their strategy is to be number 1 or number 2 in their business (or else!). For the new CEO of a Fortune 100 company, the strategy is “to grow.” For an energy company executive, the strategy is to “make key acquisitions.” A software developer says, “Our strategy is our people.” The strategy of a leading nonprofit is to “double the number of people we serve.” And then there is Google’s famous “Don’t be evil.” Is that a strategy? No. Because none of the above would qualify as a “strategy,” which for Porter is shorthand for “a good competitive strategy that will result in sustainably superior performance.” None of the above formulations tells you what will enable the organization in question to outperform the competition. Some tell you what their goal or aspiration is; others highlight key actions; some single out values. But none of them really tackles the core question, performance in the face of competition. What value will your organization create? And how will you capture some of that value for yourself?

-

Strategy explains how an organization, faced with competition, will achieve superior performance

-

Athletes vie with each other to see who will be crowned “the best.” They focus on outperforming their rivals. They compete to win. But in sports, there is one contest with one set of rules. There can be only one winner. Business competition is more complex, more open ended and multidimensional. Within an industry, there can be multiple contests, not just one, based on which customers and needs are to be served. McDonald’s is a winner in fast food, specifically fast burgers. But In-N-Out Burger thrives on slow burgers. Its customers are happy to wait ten minutes or more (an eternity by McDonald’s stopwatch) to get nonprocessed, fresh burgers cooked to order on homemade buns. Rather than enter a particular race with a particular rival, as Porter would put it, companies can choose to create their own event

-

It’s always hard to break a mental habit, but harder still if you are unaware that you have one in the first place. That’s the problem with the competition-to-be-the-best mind-set. It is typically a tacit way of thinking, not an explicit model. The nature of competition is simply taken for granted. But, says Porter, it shouldn’t be. In the vast majority of businesses, there is simply no such thing as “the best.” Think about it for a moment. Is there a best car? A best hamburger? A best mobile phone?

-

If rivals all pursue the “one best way” to compete, they will find themselves on a collision course. Everyone in the industry will listen to the same advice and follow the same prescription. Companies will benchmark each other’s practices and products (see “One-Upmanship Is Not Strategy”). Competing to be the best leads inevitably to a destructive, zero-sum competition that no one can win. As offerings converge, gain for one becomes loss for the other. This is the very essence of “zero sum.” I win only if you lose

-

If rivals all pursue the “one best way” to compete, they will find themselves on a collision course

-

The airline industry has suffered from this sort of competition for decades. If American Airlines tries to win new customers by offering free meals on its New York to Miami route, then Delta will be forced to match it—leaving both companies worse off. Both will have incurred added costs, but neither will be able to charge more, and neither will end up with more seats filled. Every time one company makes a move, its rivals will jump to match it. With everyone chasing after the same customer, there will be a contest over every sale

-

Over time, rivals begin to look alike as one difference after another erodes. Customers are left with nothing but price as the basis for their choices. This has happened in airlines, in many categories of consumer electronics, and in personal computers, with the notable exception of Apple, the one major company in that industry that has consistently marched to its own drummer

-

In what classical economic theory calls “perfect competition,” evenly matched rivals selling equivalent products go head to head, driving prices (and profits) down. This, for Porter, is the essence of competition to be the best. According to classical theory, perfect competition is the most efficient way to promote social welfare. The lesson taught in Econ 101 is that what’s good for customers (lower prices) is bad for companies (lower profits), and vice versa

-

Porter offers a more nuanced and complex view of what actually happens when companies compete to be the best. Customers may benefit from lower prices as rivals imitate and match each other’s offerings, but they may also be forced to sacrifice choice. When an industry converges around a standard offering, the “average” customer may fare well. But remember that averages are made up of some customers who want more and some who want less. There will be individuals in both groups who will not be well served by the average

-

The needs of some customers may be overserved by what the industry offers. In plain English, you will pay more for features you don’t need. As I write this, it’s hard not to think about my word processing software. It is also true of most of the appliances in my kitchen. These products have become unnecessarily complex and feature-laden for my needs, and I am both a professional writer and an accomplished cook. As they have become more complex, they have also become more prone to costly failures

-

The needs of other customers may be underserved. Think about the last flight you took. It probably met the basic need of getting you where you needed to be. But was it a pleasant experience? Are you eager to fly again?

-

When choice is limited, value is often destroyed. As a customer, you are either paying too much for extras you don’t want, or you are forced to make do with what’s offered, even if it’s not really what you need

-

For companies, the picture isn’t any brighter. With all companies heading for the stay in the lead for long. Competitive advantage will be temporary. Companies work hard, but their gains in quality and cost are not rewarded with attractive profitability. In turn, chronically poor profitability undermines investment in the future, making it harder to improve value for customers or fend off rivals

-

Head-to-head competition is rarely “perfect” for either customers or the companies that serve them. Yet Porter notes with some alarm that it is precisely this kind of zero-sum competition that has come increasingly to dominate management thinking

-

For Porter, strategic competition means choosing a path different from that of others. Instead of competing to be the best, companies can—and should—compete to be unique. This concept is all about value. It’s about uniqueness in the value you create and how you create it

-

Strategic competition means choosing a path different from that of others

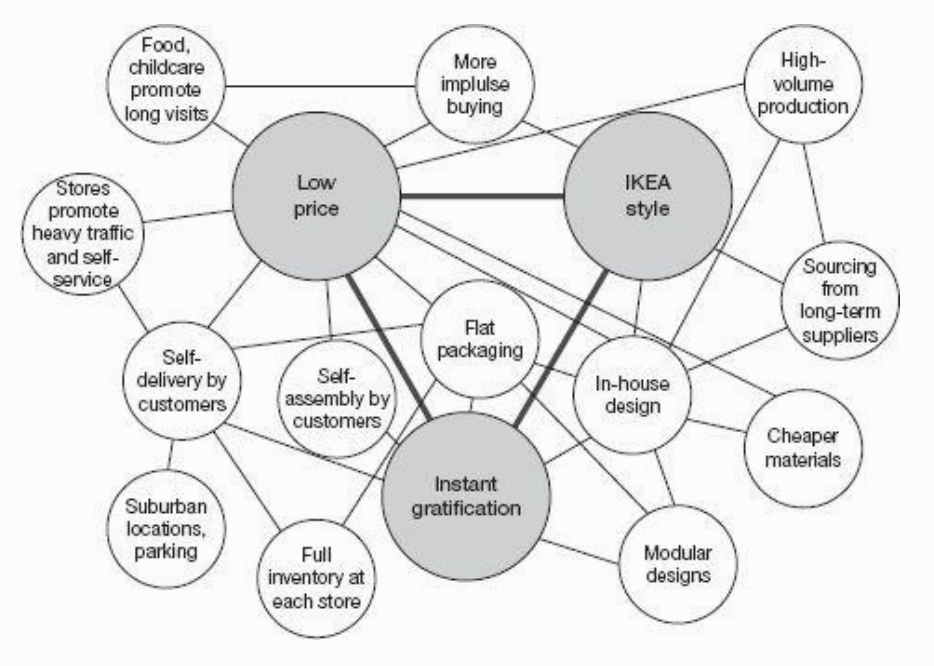

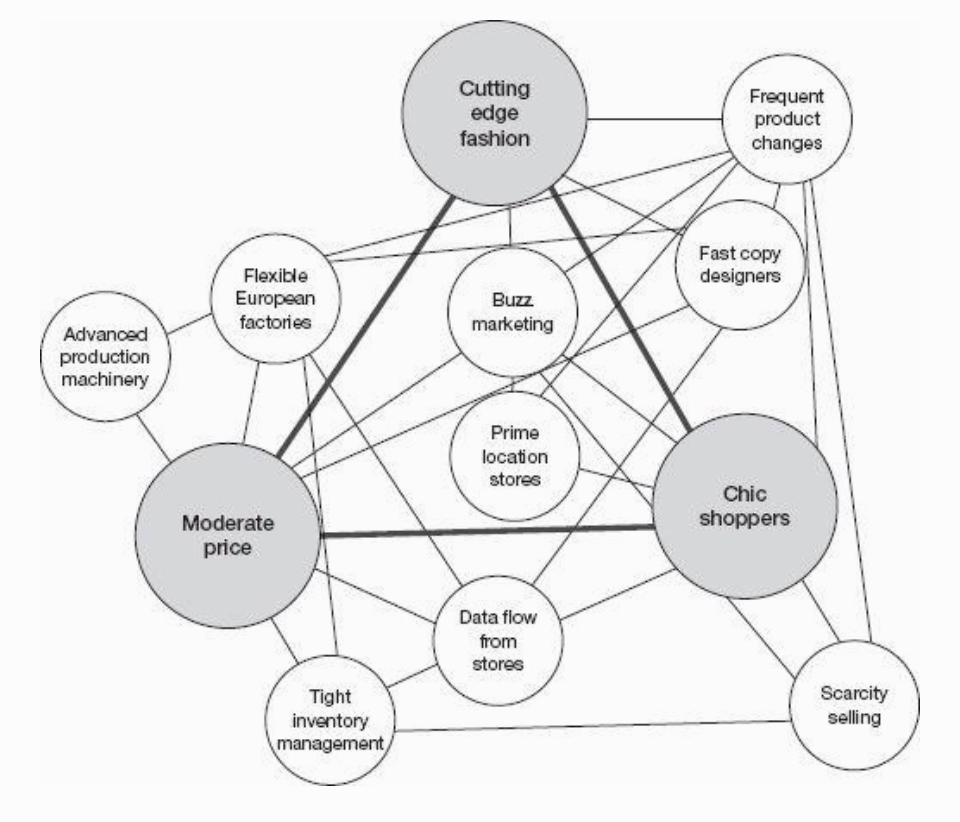

- Competition to be unique reflects a different mind-set and a different way of thinking about the nature of competition. Here, companies pursue distinctive ways of competing aimed at serving different sets of needs and customers. The focus, in other words, is on creating superior value for the chosen customers, not on imitating and matching rivals. Here, because customers have real choices, price is only one competitive variable. Some competitors, such as Vanguard or IKEA, will have strategies emphasizing low price. Others, such as BMW, Apple, or Four Seasons, will command a premium price by offering different features or service levels. Customers will pay more (or less) depending on how they perceive the value that’s offered to them

-

The real point of competition is not to beat your rivals. It’s not about winning a sale. The point is to earn profits. Competing for profits is more complex. It’s a struggle involving multiple players, not just rivals, over who will capture the value an industry creates. It’s true, of course, that companies compete for profits with their rivals. But they are also engaged in a struggle for profits with their customers, who would always be happier to pay less and get more. They compete with their suppliers, who would always be happier to be paid more and deliver less. They compete with producers who make products that could, in a pinch, be substituted for their own. And they compete with potential rivals as well as existing ones, because even the threat of new entrants places limits on how much they can charge their customers

-

The real point of competition is not to beat your rivals. It’s to earn profits

-

The five forces framework zeroes in on the competition you face and gives you the baseline for measuring superior performance. It explains the industry’s average prices and costs, and therefore the average industry profitability you are trying to beat. Before you can make sense of your own performance (current and potential), you need insight into the industry’s fundamental economics

-

The five forces framework explains the industry’s average prices and costs, and therefore the average industry profitability you are trying to beat

-

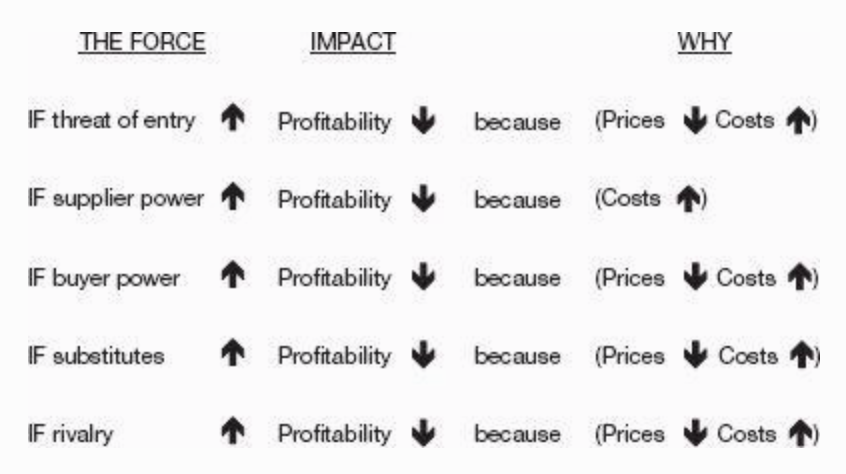

Each of the five forces has a clear, direct, and predictable relationship to industry profitability. Here’s the general rule: the more powerful the force, the more pressure it will put on prices or costs or both, and therefore the less attractive the industry will be to its incumbents. (A reminder: Industry structure is always analyzed from the perspective of companies already in the industry. Because potential entrants must overcome entry barriers, this explains why an industry can be “attractive” to incumbents while at the same time not attracting new competitors.)

-

The Fundamental Equation: Profit = Price – Cost

-

At its heart, business competition is about the struggle for profits, the tug-of-war over who gets to capture the value an industry creates. As complex and multidimensional as competition typically is, the math of profitability is simple. Porter reminds us to stay focused on the ultimate goal—profit—and on its two components, price and cost: Unit Profit Margin = Price – Cost

-

Costs include all of the resources used in competing, including the cost of capital. These are the resources that the industry transforms to create value. Prices reflect how customers value the industry’s offerings, what they are willing to pay as they weigh their alternatives

-

Note that if an industry doesn’t create much value for its customers, prices will barely cover costs. If the industry creates a lot of value, then structure becomes critical in understanding who gets to capture it. Industries can, and often do, create a lot of value for their customers or suppliers while the companies themselves earn very little for their efforts

-

Within a given industry, the relative strength of the five forces and their specific configuration determine the industry’s profit potential because they directly impact the industry’s prices and its costs. Here’s how each force works:

- Any successful company has positioned itself favorably in relation to the forces that matter most in its industry. But let me stress that one of the great clarifying disciplines of Porter’s approach is to force you to think clearly about your industry’s structure. Start there. Then you can focus on your own and rivals’ relative positions within the industry

Buyers

-

If you have powerful buyers (that is, customers), they will use their clout to force prices down. They may also demand that you put more value into the product or service. In either case, industry profitability will be lower because customers will capture more of the value for themselves

-

Consider the cement industry. In the United States, big, powerful construction companies account for a large percentage of the cement industry’s sales. They use their clout to bargain for low prices, thus dampening the profit potential for the industry. Now let’s cross the border to Mexico, where 85 percent of the cement industry’s revenues come from small, individual customers. Thousands of these “ants,” as they are called, are served by a handful of large producers. This imbalance in bargaining power between small, fragmented buyers and a few large sellers is a defining element of the structure of the Mexican cement industry. Market power allows the producers to charge higher prices and earn higher returns. It’s no surprise, then, that CEMEX, a leading producer in both countries, earns higher returns in Mexico, and not because it creates more value in its home market. In effect, CEMEX is competing in two distinct industries, each with its own structure. When you assess buyer power, the channels through which products are delivered can be as important as the end users. This is especially true when the channel influences the purchase decisions of the end-user customers. Investment advisors, for example, have enormous power, and the high margins that accompany that power. The emergence of powerful retailers like Home Depot and Lowe’s has put enormous pressure on the makers of home improvement products

- Within an industry there may be segments of buyers with more or less negotiating power, and with greater or lesser price sensitivity. Buyers are more likely to exercise their negotiating leverage if they are price sensitive. Both industrial customers and consumers tend to be more price sensitive when what they’re buying is

- Undifferentiated

- Expensive relative to their other costs or income

- Inconsequential to their own performance

- A counterexample that includes all three of these conditions is the price insensitivity of makers of major motion pictures when they buy or rent production equipment. A movie camera, for example, is a highly differentiated piece of equipment. Its price is small relative to the other costs of production, but the performance of the equipment has a big impact on the success of the movie. Here quality trumps price

Suppliers

-

If you have powerful suppliers, they will use their negotiating leverage to charge higher prices or to insist on more favorable terms. In either case, industry profitability will be lower because suppliers will capture more of the value for themselves. Makers of personal computers (PCs) have long struggled with the market power of both Microsoft and Intel. In Intel’s case, the Intel Inside campaign effectively branded what might have otherwise become a commodity component. When you analyze the power of suppliers, be sure to include all of the purchased inputs that go into a product or service, including labor (i.e., your employees). The bargaining power of strong labor unions has been a perennial drag on the airline industry. Work rules such as “receipt and dispatch,” for example, allowed only licensed mechanics to wave planes to or from airport gates, even though lower-paid baggage handlers or other ground crew were competent to perform this job. Repairs were done mostly at night, but this rule meant mechanics had to be scheduled 24/7, and the airlines had to hire many more of them than were needed for maintenance and repair. This rule, now gone, was effectively a job creation program for the high-paid mechanics, and a profit drain for the airline industry

-

How do you assess the power of suppliers and buyers? The same set of questions applies to both, so I’ll give you one list instead of two. Both suppliers and buyers tend to be powerful if:

- They are large and concentrated relative to a fragmented industry (think Goliath versus many Davids). What percentage of an industry’s purchases/sales does a supplier/buyer represent? Look at the data and map out how it is trending. How painful would it be to lose that supplier or that customer? Industries with high fixed costs (e.g., telecommunications equipment and offshore drilling) are especially vulnerable to large buyers

- The industry needs them more than they need the industry. In some cases, there may be no alternative suppliers, at least in the short term. Doctors and airline pilots, to cite two examples, have historically exercised tremendous bargaining power because their skills have been both essential and in short supply. China produces 95 percent of the world’s supply of neodymium, a rare earth metal needed by Toyota and other automakers for electric motors. Neodymium prices quadrupled in just one year (2010), as the Chinese restricted supply. Toyota is working hard to develop a new motor that will end its dependence on rare earth metals

- Switching costs work in their favor. This occurs for a supplier when an industry is tied to it, as for example, the PC industry has been to Microsoft, its dominant supplier of operating systems and software. Switching costs work in the buyer’s favor when the buyer can easily drop one vendor for another. The ease with which customers can switch from one airline to another on popular routes makes it hard for airlines to raise prices or cut service levels. Frequent flyer programs were intended to raise switching costs, but they have not been effective

- Differentiation works in their favor. When buyers see little differentiation in the industry’s products, they have the power to pit one vendor against another. “tremendous bargaining power because their skills have been both essential and in short supply. China produces 95 percent of the world’s supply of neodymium, a rare earth metal needed by Toyota and other automakers for electric motors. Neodymium prices quadrupled in just one year (2010), as the Chinese restricted supply. Toyota is working hard to develop a new motor that will end its dependence on rare earth metals

- Switching costs work in their favor. This occurs for a supplier when an industry is tied to it, as for example, the PC industry has been to Microsoft, its dominant supplier of operating systems and software. Switching costs work in the buyer’s favor when the buyer can easily drop one vendor for another. The ease with which customers can switch from one airline to another on popular routes makes it hard for airlines to raise prices or cut service levels. Frequent flyer programs were intended to raise switching costs, but they have not been effective

- Differentiation works in their favor. When buyers see little differentiation in the industry’s products, they have the power to pit one vendor against another. As the PC itself has become more of a commodity, buyer power has grown. But the PC industry’s suppliers (Microsoft and Intel) are highly differentiated. Makers of PCs are squeezed in the middle, caught between powerful suppliers and powerful buyers

- They can credibly threaten to vertically integrate into producing the industry’s product itself. Producers of beer and soft drinks have used this tactic to keep a lid on the prices of beverage containers

Substitutes

-

Substitutes—products or services that meet the same basic need as the industry’s product in a different way—put a cap on industry profitability. Tax preparation software, for example, is a substitute for a professional tax preparer such as H&R Block. Substitutes place a ceiling on the prices incumbents can sustain without eroding sales. For decades, OPEC, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, has fended off substitutes by carefully managing the price of oil to discourage investment in alternative forms of energy. This is why environmentalists favor higher gas taxes

-

Precisely because substitutes are not direct rivals, they often come from unexpected places. This makes substitutes difficult to anticipate or even to see once they appear. The threat of substitution is especially tricky when it comes at one remove. Over the next generation, for example, electric cars may (or may not!) become a significant substitute for those powered by combustion engines. If they do, this will have a cascading effect, causing substitution in many other parts of the car. Batteries add weight to a vehicle, for example, so BMW is looking at carbon fiber as a lighter substitute for the steel used in car bodies. Companies that make or service transmissions and exhaust systems could well become the buggy whip makers of the twenty-first century

-

How do you assess the threat of a substitute? Look to the economics, specifically to whether the substitute offers an attractive price–performance trade-off relative to the industry’s product. Coinstar’s Redbox—the kiosk that dispenses movie rentals for just $1—has become a tangible threat to Hollywood’s ability to sell movie DVDs at twenty to forty times that price. Redbox is a substitute for buying videos, and it is a direct rival to local video rental stores that can’t match the convenience or low cost of Redbox’s locations. While DVD rentals have long been a substitute for buying them outright, Redbox’s combination of rock bottom prices and convenience has clearly hit a customer sweet spot

-

The sweet spot isn’t always the lower-priced alternative. The Madrid–Barcelona high-speed train is a higher-value, higher-price substitute for flying. Energy drinks are a higher-price substitute for coffee. Both drinks are caffeine delivery systems, but some consumers will pay more for the substitute’s bigger jolt

-

Switching costs play a significant role in substitution. Substitutes gain ground when buyers face low switching costs, certainly the case with movie DVDs or, to cite another example, with moving from a branded drug to a generic one. Given that coffee drinking is such a deeply ingrained habit, it’s no surprise that energy drinks are more readily adopted by the young

New Entrants

-

Entry barriers protect an industry from newcomers who would add new capacity and seek to gain market share. The threat of entry dampens profitability in two ways. It caps prices, because higher industry prices would only make entry more attractive for newcomers. At the same time, incumbents typically have to spend more to satisfy their customers. This discourages new entrants by raising the hurdle they would have to clear in order to compete. In a business like specialty coffee retailing, for example, where entry barriers are low, Starbucks must constantly invest to refresh its stores and its menus. If it slacks off, it effectively opens the door for a new rival to join the fray

-

How do you size up the threat of new entry? If you are a current player, what can you do to raise those barriers? If you are thinking of entering a new industry, can you overcome the barriers that stand in your way? There are a number of different kinds of entry barriers. Start with the following questions to help you identify and assess them:

- Does producing in larger volumes translate into lower unit costs? If there are economies of scale, at what volumes do they kick in? The numbers matter. Where do these economies come from: From spreading fixed costs over a larger volume? From using more efficient technologies that are scale dependent? From increased bargaining power over suppliers? It costs about a billion dollars to develop a new operating system for a PC, costs that are recovered in a matter of weeks if you have Microsoft’s scale

- Will customers incur any switching costs in moving from one supplier to another? Switching from a Mac to a PC, or vice versa, will cost you many hours of setup and relearning. Because Apple has been the small player with low market share, it has had much more to gain from luring customers away from Microsoft. Therefore Apple has invested substantially in reducing those switching costs for PC users

- Does the value to customers increase as more customers use a company’s product? (This is called a network effect.) As with economies of scale on the supply side, try to understand where the value comes from and what it’s worth. Sometimes the perceived stability or reputation of the company makes it a “safe” choice; sometimes value may come from the size of the network, as it does with Facebook

- What is the price of admission for a company to enter the business? How large are the capital investments, and who might be willing and able to make them? Drug companies haven’t worried much about the threat of new entrants, and have therefore been free to raise prices, because the business has historically required such massive investment in R&D and marketing

- Do incumbents have advantages independent of size that new entrants can’t access? Examples include proprietary technology, well-established brands, prime locations, and access to distribution channels. The latter, for example, can be a formidable entry barrier, especially if distribution channels are limited and the industry incumbents have them locked up. This can drive new entrants to create their own channels. For example, the upstart discount airlines had to sell tickets via the Internet because travel agents tended to favor the established airlines

- Does government policy restrict or prevent new entrants? In my state of Massachusetts, licenses to sell wine are very hard to come by, severely limiting new entrants. Regulations, policies, patents, and subsidies can also work indirectly, by raising or lowering the other entry barriers

- What kind of retaliation should a potential entrant expect should it choose to enter the industry? Is this industry known for making it tough for newcomers? Does the industry have the resources to compete aggressively? If industry growth is slow or if the industry has high fixed costs, incumbents will typically fight hard to retain their share of the market

Rivalry

-

When rivalry among the current competitors is more intense, profitability will be lower. Incumbents will compete away the value they create by passing it on to buyers in lower prices or dissipating it in higher costs of competing. Rivalry can take a variety of forms: price competition, advertising, new product introductions, and increased customer service. Drug companies, for example, have a history of intense competition in R&D and in marketing, but they have steered clear of price competition

- How do you assess the intensity of rivalry? Porter notes that it is likely to be greatest if:

- The industry is composed of many competitors or if competitors are roughly equal in size and power. Often an industry leader has the ability to enforce practices that help the whole industry

- Slow growth provokes battles over market share

- High exit barriers prevent companies from leaving the industry. This happens, for example, if companies have invested in specialized assets that can’t be sold. Excess capacity typically hurts an industry’s profitability

- Rivals are irrationally committed to the business; that is, financial performance is not the overriding goal. For example, a state-owned enterprise might be propped up for reasons of national pride or because it provides jobs. Or, a corporation may feel its image requires a full product line

- Price competition, Porter warns, is the most damaging form of rivalry. The more rivalry is based on price, the more you are engaged in competing to be the best. This is most likely when:

- It is hard to tell one rival’s offerings from another (the problem of competitor convergence) and buyers have low switching costs. This typically drives rivals to lower their prices to attract customers, a practice that has dominated airline competition for many years

- Rivals have high fixed costs and low marginal costs, creating the pressure to drop prices because any new customer will “contribute to covering overhead.” Again, the essence of airline economics

- Capacity must be added in large increments, disrupting the industry’s supply–demand balance and leading to price cutting to fill capacity

- The product is perishable, an attribute that applies not only to fruit and fashion but also to a wide range of products and services that quickly become obsolete or lose their value. A hotel room, an airline seat, or a restaurant table that goes unfilled is “perishable

Buyers and Sellers

-

The five forces framework applies in all industries for the simple reason that it encompasses relationships fundamental to all commerce: those between buyers and sellers, between sellers and suppliers, between rival sellers, and between supply and demand. Think about it. This covers all of the bases. The five forces are universal and fundamental. They are the structural forces at work in every industry that systematically impact profitability in a predictable direction

-

There is a great importance of supply and demand in determining prices. In perfect markets, the adjustment is very sensitive: when supply rises, prices immediately drop to the new equilibrium. In perfect competition there are no profits because price is always driven down to the marginal cost of production. But in practice, very few markets are “perfect.” Porter’s five forces framework offers a way to think systematically about imperfect markets. If there are barriers to entry, for example, new supply can’t simply rush into the market to meet demand. The power of suppliers and buyers, for example, will have direct consequences for prices. And so on

-

Other factors may be important, but they are not structural. Consider four that get the most attention:

- Government regulation will be relevant to competition if it changes the industry’s structure through its impact on one or more of the five forces

- The same goes for technology. If the Internet, for example, makes it easier for customers in an industry to shop around for the best price, then industry profitability will drop because, in this instance, the Internet has changed the industry’s structure by increasing the power of buyers

- Managers often mistakenly assume that a high-growth industry will be an attractive one. But growth is no guarantee that the industry will be profitable. For example, growth might put suppliers in the driver’s seat, or, combined with low entry barriers, growth might attract new rivals. Growth alone says nothing about the power of customers or the availability of substitutes. The untested assumption that a fast-growing industry is a “good” industry, Porter warns, often leads to bad strategy decisions

- Finally, complements are sometimes proposed as a “sixth force.” Complements are products and services used together with an industry’s products—for example, computer hardware and software. Complements can affect the demand for an industry’s product (would you buy an electric car if you had no place to plug it in?), but like the other factors under discussion—growth, government, technology—they affect industry profitability through their impact on the five forces

Typical Steps in Industry Analysis:

- Define the relevant industry by both its product scope and geographic scope. What’s in, what’s out? This step is trickier than most people realize, so give it some real thought. The five forces help you draw the boundaries, avoiding the common pitfall of defining the industry too narrowly or too broadly. Are you facing the same buyers, the same suppliers, the same entry barriers, and so forth? Porter offers this rule of thumb: where there are differences in more than one force, or where differences in any one force are large, you are likely dealing with distinct industries. Each will need its own strategy. Consider these examples:

- Product scope. Is motor oil used in cars part of the same industry as motor oil used in trucks and stationary engines? The oil itself is similar. But automotive oil is marketed through consumer advertising, sold to fragmented customers through powerful channels, and produced locally to offset the high logistics costs of small packaging. Truck and power generation lubricants face a different industry structure—different customers and selling channels, different supply chains, and so on. From a strategy perspective, these are distinct industries

- Geographic scope. Is the cement business global or national? Recall the CEMEX example discussed earlier. Although some elements are the same, buyers are radically different in the United States and Mexico. The geographic scope is national, not global, and CEMEX will need a separate strategy for each market

- Identify the players constituting each of the five forces and, where appropriate, segment them into groups. On what basis do these segments emerge?

- Assess the underlying drivers of each force. Which are strong? Which are weak? Why? The more rigorous your analysis, the more valuable your results

- Step back and assess the overall industry structure. Which forces control profitability? Not all are equally important. Dig deeper into the most important forces in your industry. Are your results consistent with the industry’s level of profitability today and over the long term? Are the more profitable companies better positioned in relation to the five forces?

- Analyze recent and likely future changes for each force. How are they trending? Looking ahead, how might competitors or new entrants influence industry structure?

- How can you position yourself in relation to the five forces? Can you find a position where the forces are weakest? Can you exploit industry change? Can you reshape structure in your favor?

Paccar’s strategy

- Can you position your company where the forces are weakest? Consider the strategy developed by heavy-truck maker Paccar. This is another industry with an uninviting structure:

- There are many big, powerful buyers who operate large fleets of trucks; they are price sensitive because trucks represent a large piece of their costs

- Rivalry is based on price because (a) the industry is capital intensive, with cyclical downturns, and (b) most trucks are built to regulated standards and therefore look the same

- On the supplier side, unions exercise considerable power, as do the large independent suppliers of engines and drive train components

- Truck buyers face substitutes for their services (rail, for example), which puts an overall cap on truck prices

-

Between 1993 and 2007, the industry average return on invested capital (ROIC) was 10.5 percent. Yet over the same period Paccar, a company with about 20 percent of the North American heavy-truck market, earned 31.6 percent. Paccar has developed a positioning within this difficult industry where the forces are the weakest. Its target customer is the individual owner-operator, the guy whose truck is his home away from home. This customer will pay more for the status conferred by Paccar’s Kenworth and Peterbilt brands and for the ability to add a slew of custom features such as a luxurious sleeper cabin or plush leather seats. Paccar’s made-to-order products come with a number of accompanying services geared to make the owner-operator more successful. For example, Paccar’s roadside assistance program limits downtime, a key to the owner’s economics. In an industry marked by price competition, Paccar is able to charge a 10 percent price premium

-

Paccar doesn’t try to compete by being the “best” truck maker in the industry. If it did, it would go after the same customers with the same products. It would get caught up in the industry’s price competition, intensifying rivalry, which, in turn, would cause further deterioration in industry structure. The lesson here is relevant to many companies in many industries: by your own choices in how you compete, you can easily make a bad situation worse. Competing to be unique, meeting different needs or serving different customers, lets Paccar run a different race. The forces affecting its prices and costs are more benign. “Strategy,” Porter writes, “can be viewed as building defenses against the competitive forces or finding a position in the industry where the forces are weakest.” As Paccar illustrates, good strategies are like shelters in a storm. Five forces analysis will give you a weather forecast

- As some or all of the forces shift over time, industry profitability will follow. Industry structure is dynamic, not static, a point that Porter has to repeat often because there has been a remarkably persistent misconception that industry structure and positioning are static, and therefore irrelevant in a fast-changing world. To repeat, then, industry structure is dynamic, not static. When you do industry analysis, you are taking a snapshot of the industry at a point in time, but you are also assessing trends in the five forces. Over time, buyers or suppliers can become more or less powerful. Technological or managerial innovations can make new entry or substitution more or less likely. Choices managers make or changes in regulation can change the intensity of rivalry

The Five Forces: Competing for Profits key points

- The real point of competition is earning profits, not taking business away from your rivals. Business competition is about the struggle for profits, the tug-of-war over who gets to capture the value an industry creates

- Companies compete for profits with their direct rivals, but also with their customers, their suppliers, potential new entrants, and substitutes

- The collective strength of the five forces determines the average profitability of the industry through their impact on prices, costs, and the investment required to compete. A good strategy produces a P&L better than this industry average baseline

-

Using five forces analysis simply to declare that an industry is attractive or unattractive misses its full power as a tool. Because industry structure can “explain” the income statements and balance sheets of every company in the industry, insights gained from it should lead directly to decisions about where and how to compete

- Industry structure is dynamic, not static. Five forces analysis can help anticipate and exploit structural change

Competitive advantage

-

If you have a real competitive advantage, it means that compared with rivals, you operate at a lower cost, command a premium price, or both

-

Industry structure determines the performance any company can expect just by being an “average” player in its industry. Competitive advantage is about superior performance

-

Competitive advantage is a relative concept. It’s about superior performance. What exactly does that mean? The pharmaceutical company Pharmacia & Upjohn had a seemingly impressive average return on invested capital of 19.6 percent between 1985 and 2002. During the same period, the steel manufacturer Nucor earned around 18 percent. Are these comparable returns? Should you conclude that Pharmacia & Upjohn had the superior strategy? Not at all. Relative to the steel industry, where the average return was only 6 percent, Nucor was a stellar performer. In contrast, Pharmacia & Upjohn lagged its industry, in which the superior performers earned more than 30 percent

-

Performance, Porter argues, must be defined in terms that reflect the economic purpose every organization shares: to produce goods or services whose value exceeds the sum of the costs of all the inputs. In other words, organizations are supposed to use resources effectively. The financial measure that best captures this idea is return on invested capital (ROIC). ROIC weighs the profits a company generates versus all the funds invested in it, operating expenses and capital. Long-term ROIC tells you how well a company is using its resources

-

Only if a company earns a good return can it satisfy customers in a sustainable way. Only if it uses resources effectively can it deal with rivals in a sustainable way. The logic is clear and compelling. Yet when companies choose their goals—or when they accept the goals financial markets impose on them—this basic logic is often nowhere to be seen

- When Porter questions why so few companies are able to maintain successful strategies, he often points to flawed goals as the culprit:

- Return on sales (ROS) is used widely, although it ignores the capital invested in the business and therefore is a poor measure of how well resources have been used

- Growth is another widely embraced goal, along with its sister goal, market share. Like ROS, these fail to account for the capital required to compete in the industry. Too often companies pursue unprofitable growth that never leads to superior return on capital. As Porter notes wryly when he talks to managers, most companies could instantly achieve rapid growth simply “by cutting their prices in half

- Shareholder value, measured by stock price, has proven to be a spectacularly unreliable goal, yet it remains a powerful driver of executive behavior. Stock price, Porter warns, is a meaningful measure of economic value only over the long run

-

As Southwest Airline’s former CEO Herb Kelleher observes, flawed goals such as these lead to bad decisions. “‘Market share has nothing to do with profitability,’ he says. ‘Market share says we just want to be big; we don’t care if we make money doing it. That’s what misled much of the airline industry for fifteen years, after deregulation. In order to get an additional 5 percent of the market, some companies increased their costs by 25 percent. That’s really incongruous if profitability is your purpose. In gauging competitive advantage, then, returns must be measured relative to other companies within the same industry, rivals who face a similar competitive environment or a similar configuration of the five forces. Performance is meaningfully measured only on a business-by-business basis because this is where competitive forces operate and competitive advantage is won or lost

- A company’s performance has two sources: Relative price and Relative cost

-

If a company has a COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE, it can sustain higher relative prices and/or lower relative costs than its rivals in an industry

-

To answer Why are some companies more profitable than others?, first disaggregate the overall profitability number into its two components, price and cost. This is done because the underlying causal factors, the drivers of price and cost, are so different, and the implications for action are different as well

Relative Price

-

A company can sustain a premium price only if it offers something that is both unique and valuable to its customers. Apple’s hot, must-have gadgets have commanded premium prices. Ditto for the high-speed Madrid-to-Barcelona train and the trucks Paccar creates for owner-operators. Create more buyer value and you raise what economists call willingness to pay (WTP), the mechanism that makes it possible for a company to charge a higher price relative to rival offerings

-

In industrial markets, value to the customer (which Porter calls buyer value) can usually be quantified and described in economic terms. A manufacturer might pay more for a piece of machinery because, compared with lower-priced alternatives, it will produce offsetting labor costs that exceed the higher price. With consumers, buyer value may also have an “economic” component. For example, a consumer will pay more for prewashed salad in order to save time. But rarely do consumers actually figure out what they are paying for convenience, in the way a business customer would. (I once calculated, for example, that consumers were effectively paying well over $100 an hour for the unskilled labor involved in grating cheese.) A consumer’s WTP is more likely to have an emotional or intangible dimension, whether it is the trust engendered by an established brand or the status associated with owning the latest electronic gadget. Automakers are betting that consumers will pay a price premium for hybrid cars that well exceeds their potential savings from lower fuel costs. Clearly, noneconomic factors are at work in this calculation. The same is true in a small but growing corner of the food business. Why are consumers increasingly willing to pay price premiums of three or four hundred percent for what has long been a basic commodity, a carton of eggs? There are a variety of explanations, all of them related to a growing awareness of how eggs are produced on factory farms. For the health-conscious customer, the added value is food safety. For the farm-to-table enthusiast, it’s better taste. For the animal ethicist, it’s the humane treatment of the hens that lay the eggs

-

The ability to command a higher price is the essence of differentiation, a term Porter uses in this somewhat idiosyncratic way. Most people hear the word and immediately think “different,” but they might apply that difference to cost as well as to price. For example, “Ryanair’s low costs differentiate it from other airlines.” Marketers have their own definition of differentiation: it’s the process of establishing in customers’ minds how one product differs from others. Two brands of yogurt may sell for the same price, but you’re told that Brand A has “50 percent fewer calories.”

-

Porter is after something different. He is focused on tracking down the root causes of superior profitability. He is also trying to encourage more precise and rigorous thinking by underscoring the distinction between price effects and cost effects. For Porter, then, differentiation refers to the ability to charge a higher relative price. My advice here: Don’t get hung up on the language, as long as you don’t get sloppy about the underlying distinction. Remind yourself that the goal of strategy is superior profitability and that one of its two possible components two possible components is relative price—that is, you are able to charge more than your rivals charge

Relative Cost

-

The second component of superior profitability is relative cost—that is, you manage somehow to produce at lower cost than your rivals. To do so, you have to find more efficient ways to create, produce, deliver, sell, and support your product or service. Your cost advantage might come from lower operating costs or from using capital more efficiently (including working capital), or both

-

Dell Inc.’s low relative costs up through the early 2000s came from both sources. Vertically integrated rivals, such as Hewlett-Packard, designed and manufactured their own components, built computers to inventory, and then sold them through resellers. Dell sold direct, building computers to customer orders using outsourced components and a tightly managed supply chain. These competing approaches had very different cost and investment profiles. Dell’s model required little capital since the company did not design or make components, nor did it carry much inventory. In the late 1990s, Dell had a substantial advantage in days of inventory carried. Because component costs were then dropping so fast, buying components weeks later, as Dell effectively did, translated into lower relative costs per PC. And Dell’s customers actually paid for their PCs before Dell had to pay its suppliers. Most companies have to finance the working cap

-

Most companies have to finance the working capital they need to run their business. Dell’s strategy resulted in negative working capital, which further enhanced Dell’s cost advantage. Sustainable cost advantages normally involve many parts of the company, not just one function or technology. Successful cost leaders multiply their cost advantages. They are not just “low-cost producers”—a commonly used phrase that implies that cost advantages come only from the production area. Typically, the culture of low cost permeates the entire company, as it does with companies as diverse as Vanguard (financial services), IKEA (home furnishings), Teva (generic drugs), Walmart (discount retailing), and Nucor (steel manufacture). Not only has Nucor historically achieved cost advantages in production, for example, but for years it ran a multibillion-dollar company out of a corporate headquarters about the size of a dentist’s office. The “executive dining room” was the deli across the street.

-

The big idea here is this: strategy choices aim to shift relative price or relative cost in a company’s favor. Ultimately, of course, it’s the spread between the two that matters: any strategy must result in a favorable relationship between relative price and relative cost. A distinct strategy will produce its own unique structure. One strategy might, for example, result in 20 percent higher costs but 35 percent higher price. Companies such as Apple or BMW lean in that direction. Another strategy might lead to 10 percent lower costs and 5 percent lower price. Companies such as IKEA and Southwest have chosen this kind of structure. Where the net result of the configuration is positive, the strategy has, by definition, created competitive advantage. For Porter, thinking in such precise, quantifiable terms is essential because it ensures that strategy is economically grounded and fact based

-

Strategy choices aim to shift relative price or relative cost in a company’s favor

The Value Chain

-

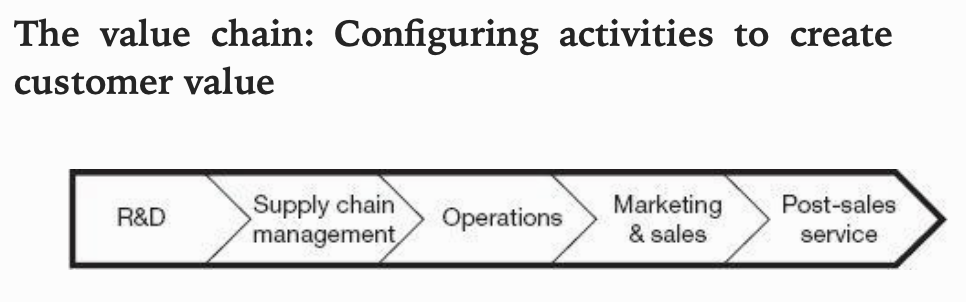

Definition of competitive advantage: superior performance resulting from sustainably higher prices, lower costs, or both. But we have to peel one final layer of the onion to arrive at managerially relevant sources of competitive advantage—the things that managers can control. Ultimately, all cost or price differences between rivals arise from the hundreds of activities that companies perform as they compete

-

Activities are discrete economic functions or processes, such as managing a supply chain, operating a sales force, developing products, or delivering them to the customer. An activity is usually a mix of people, technology, fixed assets, sometimes working capital, and various types of information

-

The sequence of activities your company performs to design, produce, sell, deliver, and support its products is called the value chain. In turn, your value chain is part of a larger value system: the larger set of activities involved in creating value for the end user, regardless of who performs those activities. An automaker, for example, has to equip a car with tires. This involves a number of upstream choices: Do you make the tires yourself or buy them from a supplier? If you make them yourself, do you buy raw materials from a supplier or do you produce them yourself? Henry Ford famously chose to operate his own rubber plantation in Brazil in the late 1920s, a decision that did not turn out too well. Ultimately, choices like this, about how vertically integrated you want to be, are choices every company makes about “where to sit” in the value system

-

There are also activity choices to be made looking downstream in the value system. In the 1920s, when cars were still rich men’s toys, General Motors and other automakers started their own consumer finance divisions to help customers buy cars on credit. Henry Ford, a man of strong convictions, believed that credit was immoral. He refused to follow GM’s lead. By 1930, 75 percent of cars and trucks were bought “on time,” and Ford’s once dominant market share had plummeted. In thinking about your value chain, then, it’s important to see how your activities have points of connection with those of your suppliers, channels, and customers. The way they perform activities affects your cost or your price, and vice versa

-

The value chain is a powerful tool for disaggregating a company into its strategically relevant activities in order to focus on the sources of competitive advantage, that is, the specific activities that result in higher prices or lower costs

Key Steps in Value Chain Analysis

- Start by laying out the industry value chain. Every established industry has one or more dominant approaches. These reflect the scope and sequence of activities that most of the companies in that industry perform, and this is as true for nonprofits as for any business

- The industry’s value chain is effectively its prevailing business model, the way it creates value

- How far upstream or downstream do the industry’s activities extend?

- What are the key value-creating activities at each step in the chain?

- Compare the value chains of rivals in an industry to understand differences in prices and costs

-

How far upstream do the industry’s activities extend? Does the industry do basic research? Does it design and develop its products? Does it manufacture? What key inputs does it rely on? Where do they come from? How does the typical player in the industry market, sell, distribute, deliver? Is financing or after-sales service a part of the value the industry creates for customers?

- Depending on the industry, some categories will be more or less important in competitive advantage. The key here is to lay out the major value-creating activities specific to your industry. If there are competing business models, lay out the value chain for each one. Then look for differences among rivals

- Next, compare your value chain to the industry’s. You can use a template like the one used in the example in this section. The goal is to capture every major step in the value-creating process. For illustrative purposes, I’ve chosen an example from the nonprofit world, which has the advantage of simplicity

-

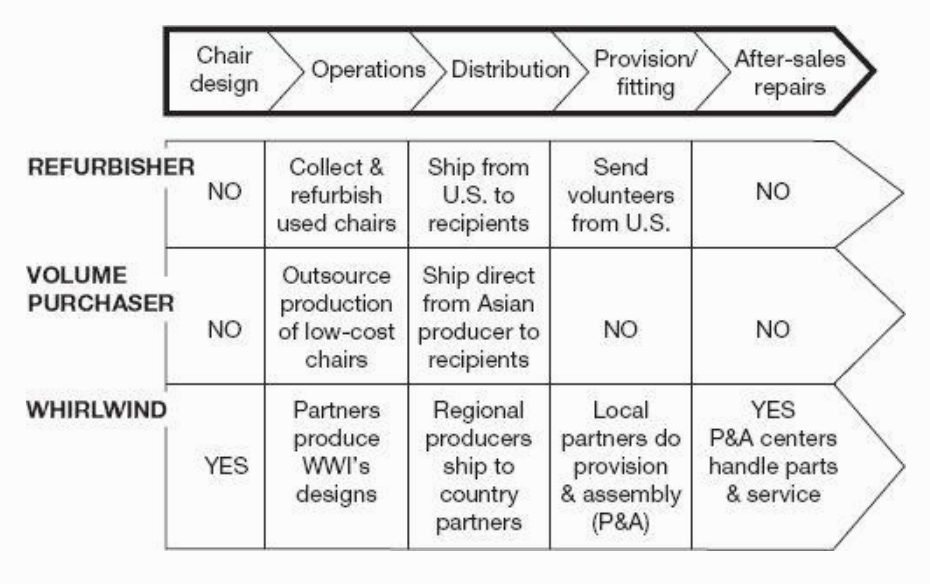

Consider that a number of U.S.-based nonprofits provide wheelchairs to people with disabilities in developing countries. One strategy, which I’ll call the “refurbisher,” consists of three major activities and looks something like this

- Product sourcing. Used chairs donated by hospitals, individuals, and manufacturers are collected and then refurbished

- Distribution/delivery. Wheelchairs are shipped to recipients overseas; an in-country charity or nongovernmental organization distributes the chairs to end users

-

Custom fitting. Professionals (typically volunteers) follow the chairs overseas to custom-fit each chair. This service, called provision, is important because an ill-fitting wheelchair can create its own health issues

-

An even simpler strategy, “volume purchaser,” consists of just two primary activities: fundraising and buying huge volumes of the most basic, standardized chairs from the lowest-cost producers in China. These are distributed without provision or other user services. Here, the value created is as stripped down as the value chain: no design, no provision, no repairs

-

Whirlwind Wheelchair International (WWI) takes a different approach, starting with a different way of thinking about the value it wants to create. When founder Ralf Hotchkiss was a college student in 1966, a motorcycle accident left him paralyzed. The first time he took his wheelchair out on the street, he hit a crack in the sidewalk and the chair broke. Hotchkiss, an engineer and a bicycle maker, has spent the last forty years redesigning wheelchairs, not only for his own use but also and especially for people in developing countries where the physical conditions are particularly challenging. His most famous design is called the Rough Rider

- Consider Whirlwind’s value chain activities:

- Product sourcing. Rather than accept donations of what Hotchkiss calls “hospital chairs,” good only for maneuvering indoors, he starts further upstream in order to create true “mobility” chairs. A team of designers based at San Francisco State University works with wheelchair users, designing chairs to fit their lives and withstand local conditions. Adding user-originated design to the value chain creates a higher-value product

- Manufacturing. Whirlwind works with a handful of regional manufacturers outside the United States, partners large enough to achieve efficient scale and sophisticated enough to meet Whirlwind’s quality standards

- Distribution. Where feasible, chairs are shipped to the end-use countries flat packed. This cuts shipping costs in half and allows for some local value-added at the final destination. Centers operated by local partners perform final assembly and provision, and they carry spare parts so the wheelchairs can be serviced over time. This extends their useful life and solves a big problem of the refurbisher approach: donated hospital chairs from the United States are next to impossible to repair if parts are needed

- Whirlwind’s configuration of activities produces a different kind of value with a different cost profile. Looking at competing value chains side by side highlights those differences. If your value chain looks like everyone else’s, then you are engaged in competition to be the best

-

Zero in on price drivers, those activities that have a high current or potential impact on differentiation. Do you or could you create superior value for your customers by performing activities in a distinctive way or by performing activities that competitors don’t perform? Can you create that value without incurring commensurate costs? Buyer value can arise throughout the value chain. It can come from product design, for example, as it does for Whirlwind Wheelchair. It can come from choices in the inputs used or the production process itself, both of which are key to the success of In-N-Out Burger, a chain of over 230 hamburger restaurants that uses only the freshest ingredients and prepares its limited menu on-site. It can be created by the selling experience, as any visitor to an Apple Store will tell you. Or, it can arise from after-sales support activities. Every Apple Store, for example, has a Genius Bar where customers can go for free help with technical questions. Whirlwind’s spare parts policy is another example. Whether the customer is a company or a household, examining how your activities are part of the whole value system is the key to understanding buyer value

-

Zero in on cost drivers, paying special attention to activities that represent a large or growing percentage of costs. Your relative cost position (RCP) is built up from the cumulative cost of performing all the activities in the value chain. Are there actual or potential differences between your cost structure and those of your rivals? The challenge here is to get as accurate a picture as you can of the full costs associated with each activity, including not only direct operating and asset costs but also the overhead costs that are generated because you perform this activity. To get a handle on this, you can ask yourself what specific overhead costs could be cut if you stopped performing this activity. For each activity, a cost advantage or disadvantage depends on cost drivers, or a series of influences on relative cost. The real “so what” of relative cost analysis comes when you dig deep enough into the numbers to uncover the actions you can take to improve them. The brief one provided here will give you a sense of what I mean. Southwest Airlines has long enjoyed a cost advantage, as measured in its low relative cost per available seat mile. To understand why, you would list all of Southwest’s activities, assign costs to them, and then compare the results with those of other carriers. Let’s follow the trail on just one activity: gate turnarounds. Southwest does it faster, and as a result it gets more out of its assets—its costs per plane and per employee are lower than those of rivals. Seeing that gate turnarounds are a significant cost driver, you would then dive a level deeper, to the many specific subactivities involved in gate turnarounds. Here you’d be looking for ways to lower your costs without sacrificing customer value. This is how you drive an even greater wedge between your performance and that of your rivals. When a plane lands, for example, the lavatories have to be drained. To do this, a piece of equipment is hooked up to a service panel. The problem, Southwest discovered, was that this interfered with the ground crew’s other servicing activities. The solution: Southwest got its supplier, Boeing, to reposition the service panel in the new 737-300. As the Southwest example shows, ferreting out cost drivers can be like detective work. It demands both creativity and rigorous analysis. The easier path is simply to accept the industry’s conventional wisdom. Most auto companies in the 1990s, for example, accepted on faith that scale was the decisive cost driver, that if you didn’t sell at least four million cars a year, your costs would kill you. A frenzy of consolidation, much of it subsequently undone, followed. Of course, scale matters in the auto industry. But a deeper understanding of the cost drivers is critical. Honda, for example, is a relatively small car company. This might lead you to conclude that Honda would have a cost disadvantage. But Honda is the world’s largest producer of motorcycles, and overall it is a huge producer of engines. Since engines account for 10 percent of the cost of a car and Honda can share the cost of engine development across its product lines, this scope advantage offsets its overall lack of scale. Moreover, Honda’s focus on engine development is an element of differentiation that supports its pricing

Do You Really Have a Competitive Advantage? First You Quantify, and Then You Disaggregate

- How does the long-term profitability in each of your businesses stack up against other companies in the economy? In the United States, from 1992 to 2006, the average company earned about 14.9 percent return on equity (earnings before interest and taxes divided by average invested capital less excess cash), although this varied somewhat over the business cycle. Are the returns for your business better or worse? If better, something is working in your favor. If worse, then something is wrong. In either case, dig deeper into the underlying causes

- Now compare your performance to the average return in your industry, and do so over the last five to ten years. Profitability can fluctuate in the short run as a result of a number of factors as transient as the weather. Choose a longer time horizon, ideally one that matches the investment cycle of your industry. This will tell you whether or not you have a competitive advantage. Suppose company A earns a 15 percent return against a national benchmark of 13 percent and an industry benchmark of 10 percent. The analysis of industry structure will explain why the industry overall is 3 points below the national average. But A’s superior performance—it exceeds its industry by 5 points—indicates that it has a competitive advantage. So in this case, A does not have a strategy problem. On the other hand, it does have to deal with a challenging industry structure. The distinction between these two sources of profitability is crucial because the factors that affect industry structure and those that determine relative position are very different. Until a company understands where its profit performance comes from, it will be ill equipped to deal with it strategically

- Next, keep digging to understand why the business is performing better or worse than the industry average. Disaggregate your relative performance into its two components: relative price and relative cost. Relative price and cost are essential for understanding strategy and performance. In the example under discussion, company A achieved a 5 percent higher return than the average competitor. Its realized price (adjusting for concessions and discounts) was 8 percent higher than the industry average. To command that premium, company A had to spend more: in this case, its relative cost was 3 percentage points higher. That explains A’s 5 percent higher return

- Dig further. On the price side, it may be possible to trace the overall price premium (or discount) to differences in particular product lines, in customers or geographic areas, or in list price versus discounts off list. On the cost side, it is often revealing to disaggregate the cost advantage (or disadvantage) into that part due to operating cost (income statement) and that part due to the utilization of capital (balance sheet)

These basic economic relationships underlie company performance and strategy. Strategy is about trying to shape these underlying determinants of profitability

Consequences of value chain thinking

-

The first is that you begin to see each activity not just as a cost, but as a step that has to add some increment of value to the finished product or service. Over time, this perspective has revolutionized the way organizations define their business. Thirty-five years ago, for example, the brokerage business, with its hefty commissions, was how stocks were traded. One size fit all, or at least it fit those wealthy enough to afford it. Everyone took for granted that the business was what the business was. You begin to see each activity not just as a cost, but as a step that has to add some increment of value to the finished product or service. But what happens when you start thinking about that business as a collection of value-creating activities? You see that behind that broker was a fully integrated set of activities that ranged all the way from doing research and analysis of securities to executing trades to sending out monthly statements. The costs of all those activities were buried in the price of the commission. Charles Schwab created the company that bears his name—and a new category known as discount brokerage—around a different value chain. Not all customers want advice, so why should they have to pay for it? Take away all the activities needed to give advice, focus instead on executing trades, and you can create a different kind of value: low-cost trades that make stock ownership accessible to a wider customer base. Matching the value chain—the activities performed inside the company—to the customer’s definition of value was a new way of thinking just twenty-five years ago. Today it has become conventional wisdom

-

A second major consequence of value chain thinking is that it forces you to look beyond the boundaries of your own organization and its activities and to see that you are part of a larger value system involving other players. For example, if you want to build a fast food business around consistent, perfect French fries, as McDonald’s did, you can’t make excuses to customers because the potato farmer you buy from lacks proper storage facilities. Customer don’t care who’s at fault. They care only about the quality of their fries. So, McDonald’s has to perform specific activities to make sure that, one way or another, all the potato growers from whom it buys can meet its standards

-

And everyone in the value system had better understand the role they play in the larger process of value creation, even when they are removed by one or two steps from the ultimate end user. Most wine drinkers know how unpleasant it can be to uncork a nice bottle of wine, pour it for a guest, and then discover that it’s corky—that is, the taste has been ruined by a problem known as cork taint. By the 1990s, the problem reached a tipping point for wine makers and sellers. They wanted cork makers to fix it. You don’t want a cheap, commodity-like component to ruin the value of an expensive product. Cork, most of which comes from trees in Portugal and other Mediterranean countries, has enjoyed a near monopoly on wine closures not just for decades, but for centuries. No surprise, then, that the cork makers were slow to respond. Their skill lay in harvesting cork from the outer bark of cork oaks without damaging the trees. They were hand workers—basically farmers, not chemists. This created an opportunity for plastics makers such as Nomacorc to step into the breech. Nomacorc’s value chain made it relatively easy for it to undertake research into the chemistry of wine taint, and to solve the problem. While the traditional cork makers were stuck in an older mind-set (“we’re in the cork business”), the plastics makers could see how to become part of a larger value-creating process. By 2009, Nomacorc’s automated North Carolina factory was churning out close to 160 million plastic stoppers a month, and synthetic corks had captured 20 percent of the market. This interdependence of value chains has enormous implications. Managing across boundaries, whether these are between the company and its customers or the company and its suppliers or business partners, can be as important for strategy as managing within one’s own company. Using Porter’s value chain construct was like looking through a microscope for the first time. Suddenly managers could see a whole world of relationships that had previously been invisible to them. The value chain was a major breakthrough for analyzing both a company’s relative cost and value. The value chain focuses managers on the specific activities that generate cost and create value for buyers. Although managers often talk about how their organization’s skills or capabilities create value, activities are where the rubber meets the road. Nomacorc clearly had what most managers would call a “core competence” in chemistry. But its competitive success in the wine market resulted from decisions to deploy those capabilities in activities that enhanced the design and manufacture of wine stoppers

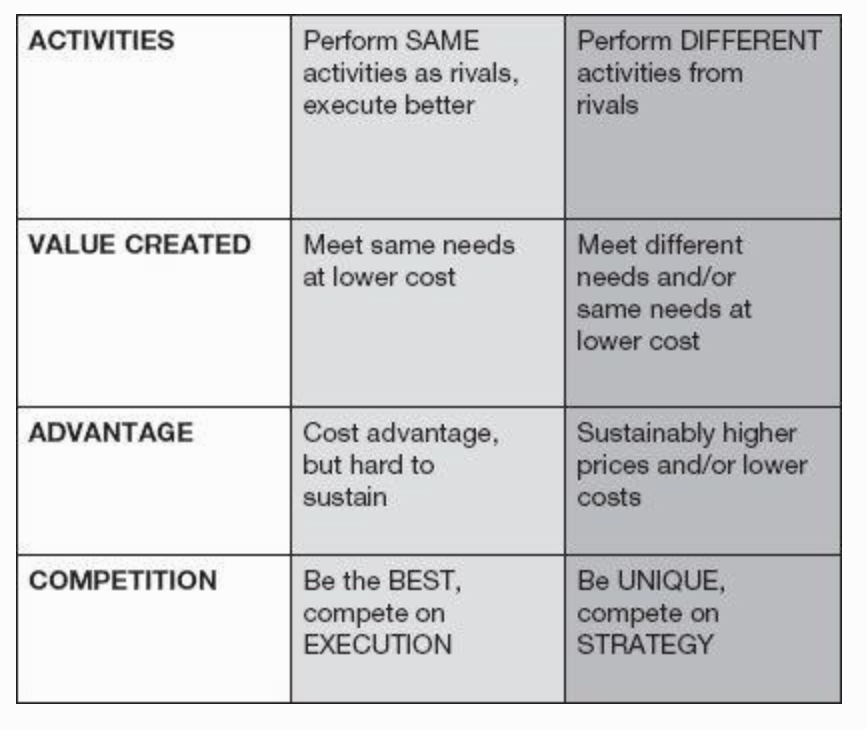

Can You Execute Your Way to Competitive Advantage?

- Complete definition of competitive advantage: a difference in relative price or relative costs that arises because of differences in the activities being performed

-

Wherever a company has achieved competitive advantage, there must be differences in activities. But those differences can take two distinct forms. A company can be better at performing the same configuration of activities, or it can choose a different configuration of activities. By now, of course, you recognize that the first approach is competition to be the best. And by now, we are in a better position to understand why this approach is unlikely to produce a competitive advantage

-

Porter uses the phrase operational effectiveness (OE) to refer to a company’s ability to perform similar activities better than rivals. Most managers use the term “best practice” or “execution.” Whichever term you prefer, we are talking about a multitude of practices that allow a company to get more out of the resources it uses. The important thing is not to confuse OE with strategy. First, let’s recognize that differences in OE are pervasive. Some companies are better than others at reducing service errors, or keeping their shelves stocked, or retaining employees, or eliminating waste. Differences like these can be an important source of profitability differences among competitors. But simply improving operational effectiveness does not provide a robust competitive advantage because rarely are “best practice” advantages sustainable. Once a company establishes a new best practice, its rivals tend to copy it quickly. This treadmill of imitation is sometimes called hypercompetition. Best practices spread rapidly, aided by the business media and by consultants who have created an industry around benchmarking and quality/continuous improvement programs. The most generic solutions, those that apply in multiple company and industry settings, diffuse the fastest. (Name an industry that has yet to be visited by some version of Total Quality Management.) Programs like these are compelling. Managers are rewarded for the tangible improvements they achieve when they implement the latest best practice inside their companies. That makes it all too easy to lose sight of the bigger picture of what’s happening outside their companies. Competing on best practices effectively raises the bar for everyone. While there is absolute improvement in OE, there is relative improvement for no one. The inevitable diffusion of best practices means that everyone has to run faster just to stay in place. No company can afford sloppy execution. Inefficiency can overwhelm even the most distinctive and potentially valuable strategies. But betting that you can achieve competitive advantage—a sustainable difference in price or cost—by performing the same activities as your rivals is a bet you will probably lose. No one has been better at OE competition than the Japanese, but, as Porter’s work documents in great detail, OE competition has led even the best of them to chronically poor profitability. Competitive rivalry, at its core, is a process working against the ability of a company to maintain differences in relative price and relative cost. Competition to be the best is the great leveler. It accelerates that process. In the next four chapters, we will see how strategy, built around a unique configuration of activities, works to achieve and sustain competitive advantage. Strategy is the antidote to competitive rivalry

The Economic Fundamentals of Competitive Advantage:

- Popular metrics such as shareholder value, return on sales, growth, and market share are misleading for strategy. The goal of strategy is to earn superior returns on the resources you deploy, and that is best measured by return on invested capital

- Competitive advantage is not about beating rivals; it’s about creating superior value and about driving a wider wedge than rivals between buyer value and cost

- Competitive advantage means you will be able to sustain higher relative prices or lower relative costs, or both, than your rivals in an industry. If you have a competitive advantage, it will show up on your P&L

- For nonprofits, competitive advantage means you will produce more value for society for every dollar spent (the analogue of higher price), or you will produce the same value using fewer resources (the equivalent of lower cost)

- Differences in relative prices and relative costs can ultimately be traced to the activities that companies perform.

- A company’s value chain is the collection of all its value-creating and cost-generating activities. The activities, and the overall value chain in which activities are embedded, are the basic units of competitive advantage

Competitive advantage and Strategy

-

Competitive advantage means you have created value for customers and you are able to capture value for yourself because the positioning you have chosen in your industry effectively shelters you from the profit-eroding impact of the five forces

-

Porter’s definition of strategy is normative, not descriptive. That is, it distinguishes a good strategy from a bad one. His focus is on content, not process. His focus is on where you want to be, not on the decision-making process by which you got there—not how, or even whether, you do formal strategic planning, nor whether your strategy can be captured in fifty words or less

-

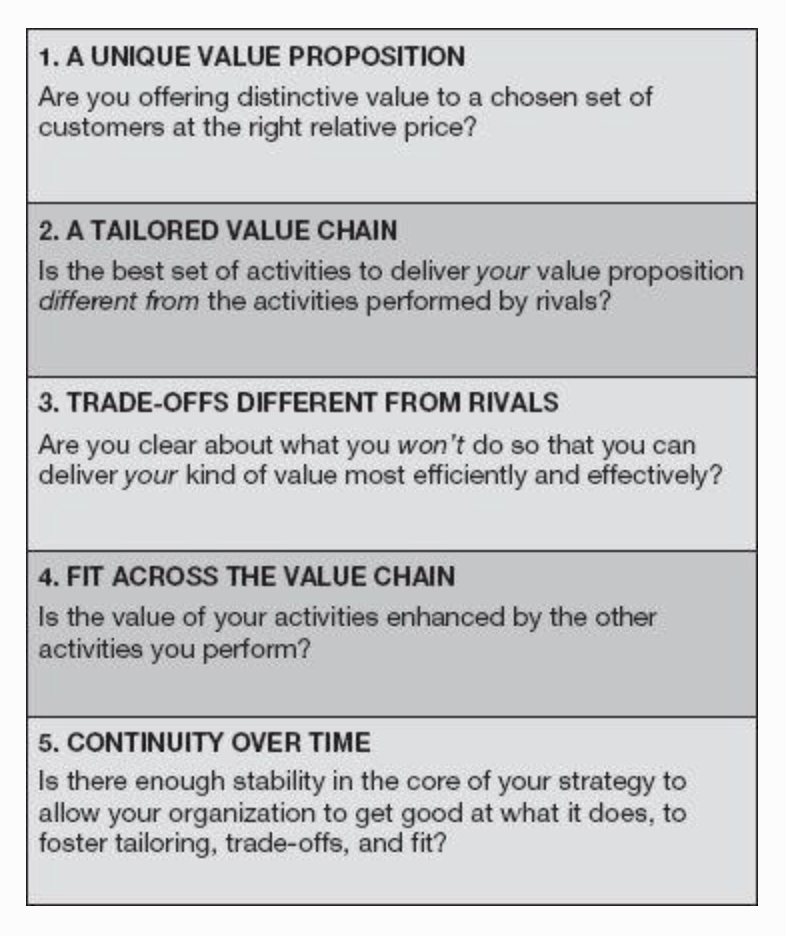

Five tests every good strategy must pass:

- A distinctive value proposition

- A tailored value chain

- Trade-offs different from rivals

- Fit across value chain

- Continuity over time

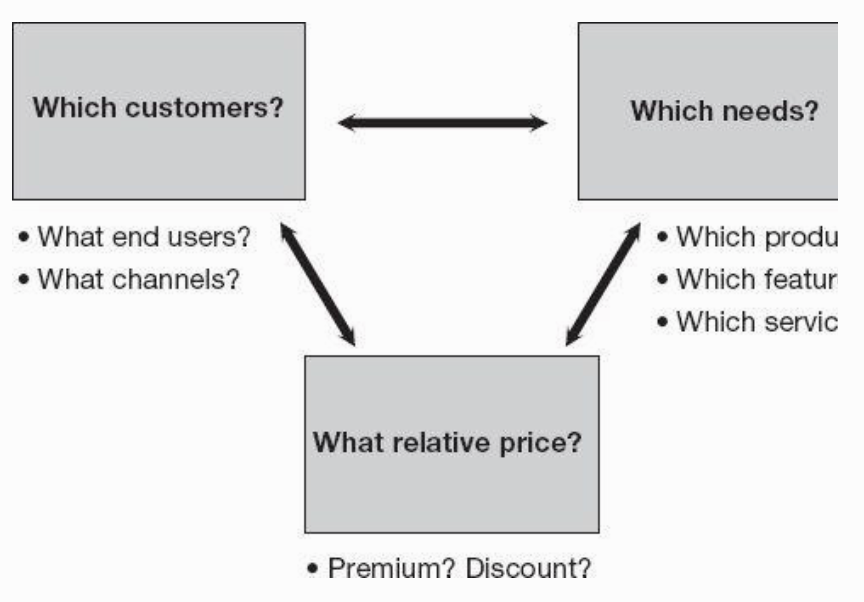

The First Test: A Distinctive Value Proposition

-

Your value chain must be specifically tailored to deliver your value proposition. A value proposition that can be effectively delivered without a tailored value chain will not produce a sustainable competitive advantage. The tailored value chain is Porter’s second test, and it is neither obvious nor intuitive

-

Strategy means deliberately choosing a different set of activities to deliver a unique mix of value. If all rivals produce the same way, distribute the same way, service the same way, and so on, they are, in Porter’s terms, competing to be the best, and not competing on strategy

-

The value proposition is the element of strategy that looks outward at customers, at the demand side of the business. A value proposition reflects choices about the particular kind of value the company will offer, whether those choices have been made consciously or not. The value chain focuses internally on operations. Strategy is fundamentally integrative, bringing the demand and supply sides together

-

Value proposition answers these questions:

Which customers?

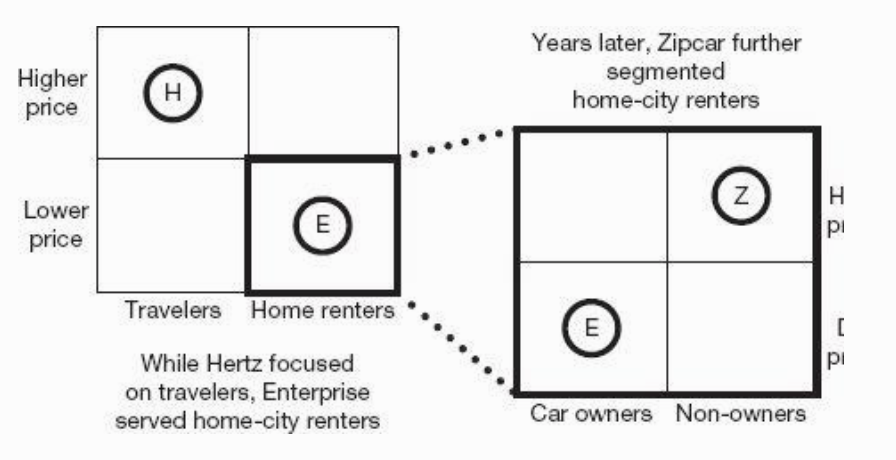

-

Within an industry, there are usually distinct groups of customers, or customer segments. A value proposition can be aimed specifically at serving one or more of these segments. For some value propositions, choosing the customer comes first. That choice then leads directly to the other two legs of the triangle: needs and relative price

-

Customer segmentation is typically part of any good industry analysis, and choosing the customer(s) you will serve can be an important anchor in your positioning vis-à-vis the five forces. In the examples that follow, note how each reflects a different basis for segmentation: Walmart’s segmentation was based on geography, Progressive’s on demographics, and Edward Jones’s on psychographics

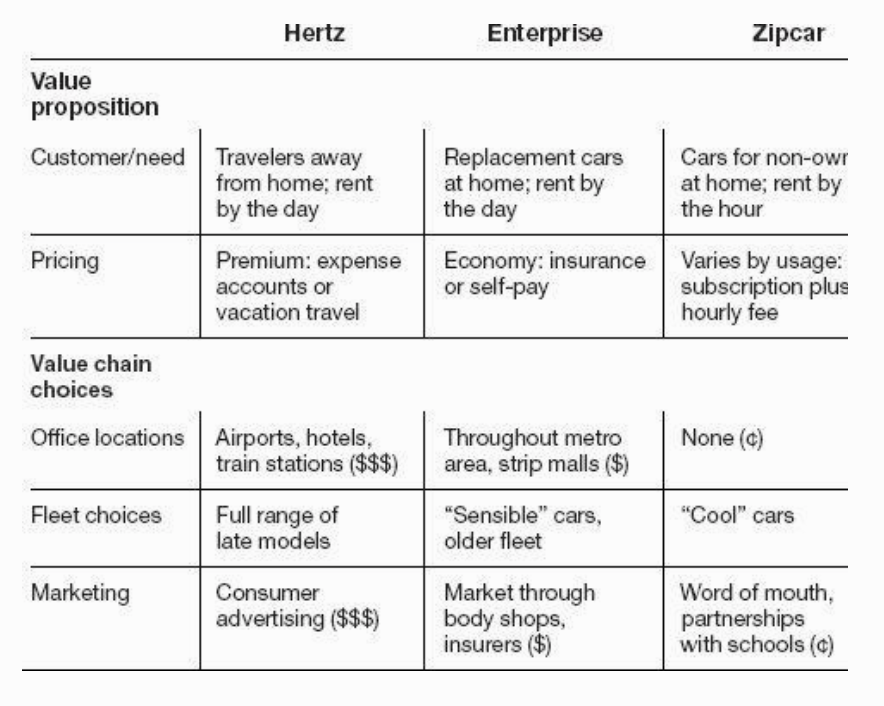

-