7 Powers - Hamilton Wright Helmer

-

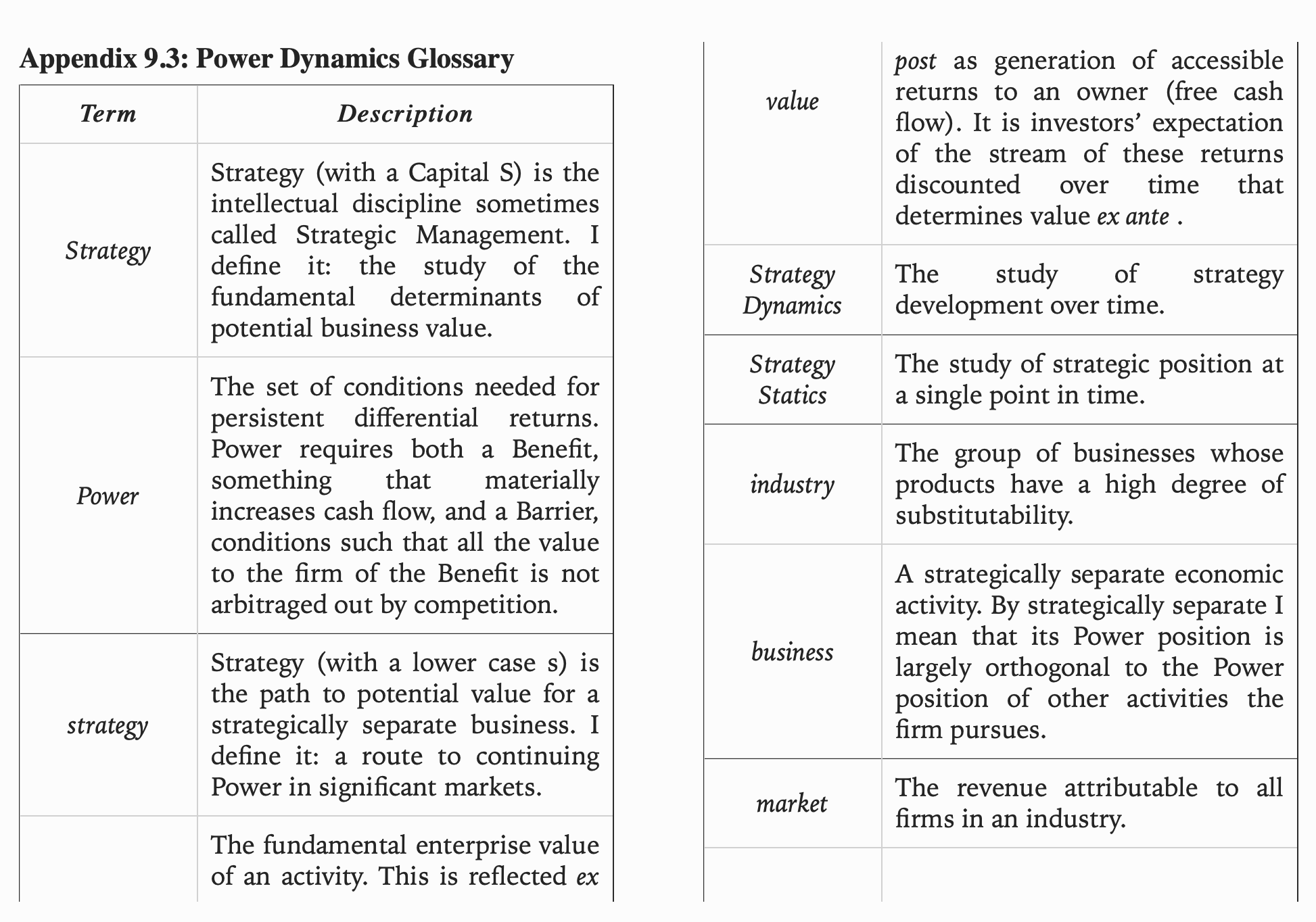

Strategy: The study of the fundamental determinants of potential business value. The objective here is both positive—to reveal the foundations of business value—and normative—to guide businesspeople in their own value-creation efforts

- Strategy can be usefully separated into two topics:

- Statics—i.e. “Being There”: what makes Intel’s microprocessor business so durably valuable?

- Dynamics—i.e. “Getting There”: what developments yielded this attractive state of affairs in the first place?

- These two form the core of the discipline of Strategy, and though interwoven, they lead to quite different, although highly complementary, lines of inquiry

-

Power: The set of conditions creating the potential for persistent differential returns

-

strategy: a route to continuing Power in significant markets

-

“Strategy” and “strategy.” are defined separately. The first tied back to value, the second to Power

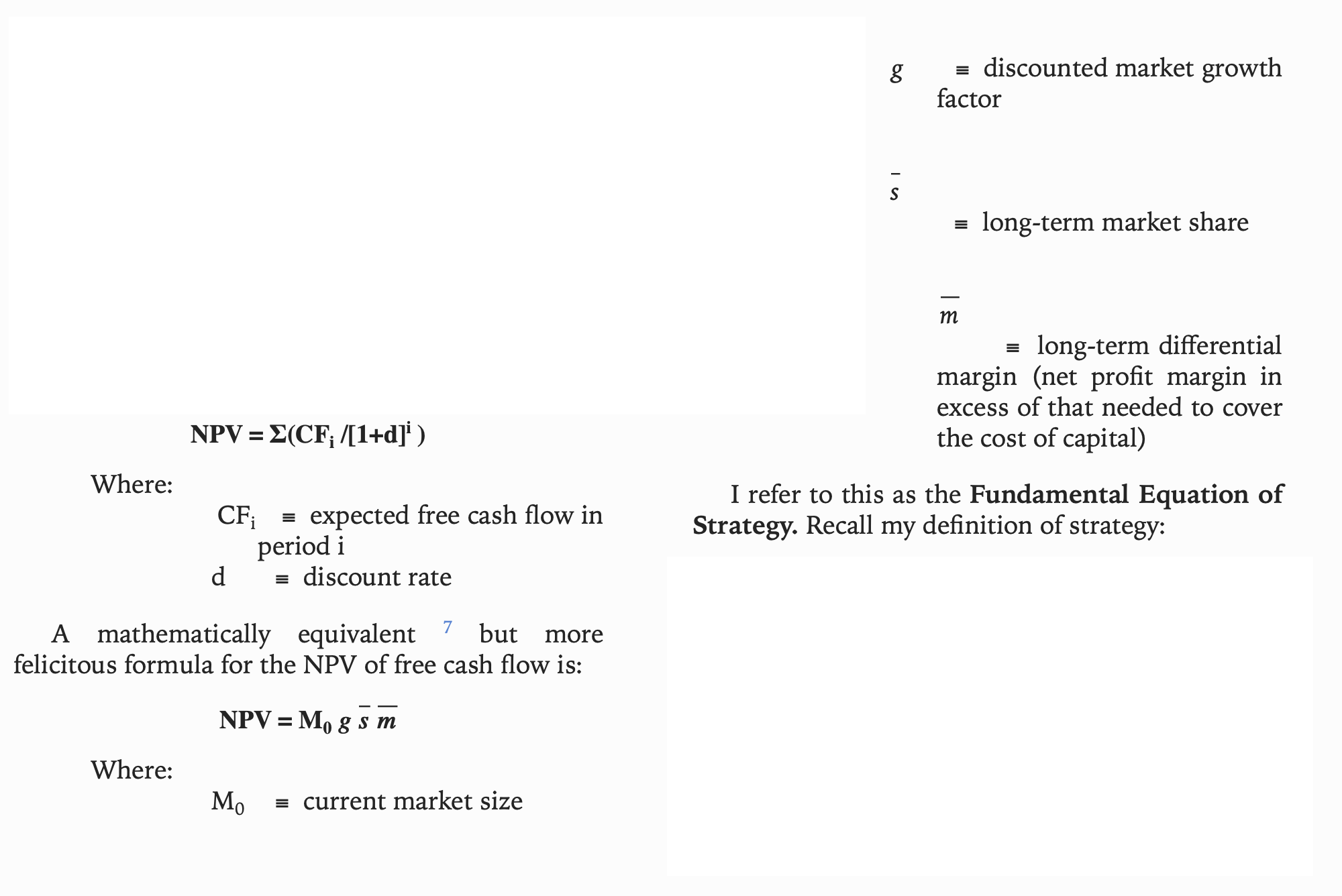

- Value refers to absolute fundamental shareholder value —the ongoing enterprise value shareholders attribute to the strategically separate business of an individual firm. The best proxy for this is the net present value (NPV) of expected future free cash flow (FCF) of that activity

-

The product of M0 and g reflect market scale over time; hence they capture the “significant markets” component of this definition. The impact of competitive arbitrage is expressed in margins and market share simultaneously, so the maintenance or increase of s market share, while maintaining a positive and material long-term differential margin, provides the numerical expression of Power. In other words, put another way:

-

Potential Value = [Market Scale] * [Power]

-

This is potential value and operational excellence is required to achieve that potential. Examining Intel through this lens, we can identify a large-scale market (M0 g) for both memories and microprocessors. So what accounted for the utterly different value outcome? Under Andy Grove, operational excellence was the norm, so it was Power that made the difference: over time competitive arbitrage drove m in memories negative, whereas Power enabled Intel to maintain a high and positive m in microprocessors

-

The Fundamental Formula of Strategy specifies unchanging m —differential margins

-

The bulk of a business’ value comes in the out years. For faster-growing companies, this reality becomes more accentuated. You won’t yield much from a few good years of positive m which then tapers off or disappears altogether. For example, let’s use a common valuation model: if a company were growing at 10% per year, the next three years would account for only about 15% of its value.Remember, we’ve reserved the term “Power” for those conditions that create durable differential returns. In other words, we are trying to discern long-term competitive equilibria, not just next year’s results. Intel’s current $150B market cap reflects not only investors’ expectations of high returns but also those which continue for a very long time

-

Thus persistence proves a key feature in this value focus, and such persistence requires that any theory of Strategy is a dynamic equilibrium theory—it’s all about establishing and maintaining an unassailable perch. Strategy requires you identify and develop those rare conditions which produce a value sinecure immune to competitive onslaught. Intel eventually achieved this in microprocessors but could never get there in memories

-

Dual Attributes: Power is as hard to achieve as it is important. As stated above, its defining feature ex post is persistent differential returns. Accordingly, we must associate it with both magnitude and duration

-

Benefit: The conditions created by Power must materially augment cash flow, and this is the magnitude aspect of our dual attributes. It can manifest as any combination of increased prices, reduced costs and/or lessened investment needs

-

Barrier: The Benefit must not only augment cash flow, but it must persist, too. There must be some aspect of the Power conditions which prevents existing and potential competitors, both direct and functional, from engaging in the sort of value-destroying arbitrage Intel experienced with its memory business. This is the duration aspect of Power

-

The Benefit conditions probably won’t sound all too rare—they are met often in business. Indeed, every major cost-cutting initiative qualifies. The Barrier conditions, on the other hand, prove far rarer, a reality that merely proves the ubiquity of competitive arbitrage. As a strategist, then, my advice is, “Always look to the Barrier first.” In Intel’s case, the heart of its microprocessors strategy can be best understood not by sorting through the multiplicity of Intel’s value improvements, but by deducing why decades of capable and committed competition failed to emulate or undermine those improvements

-

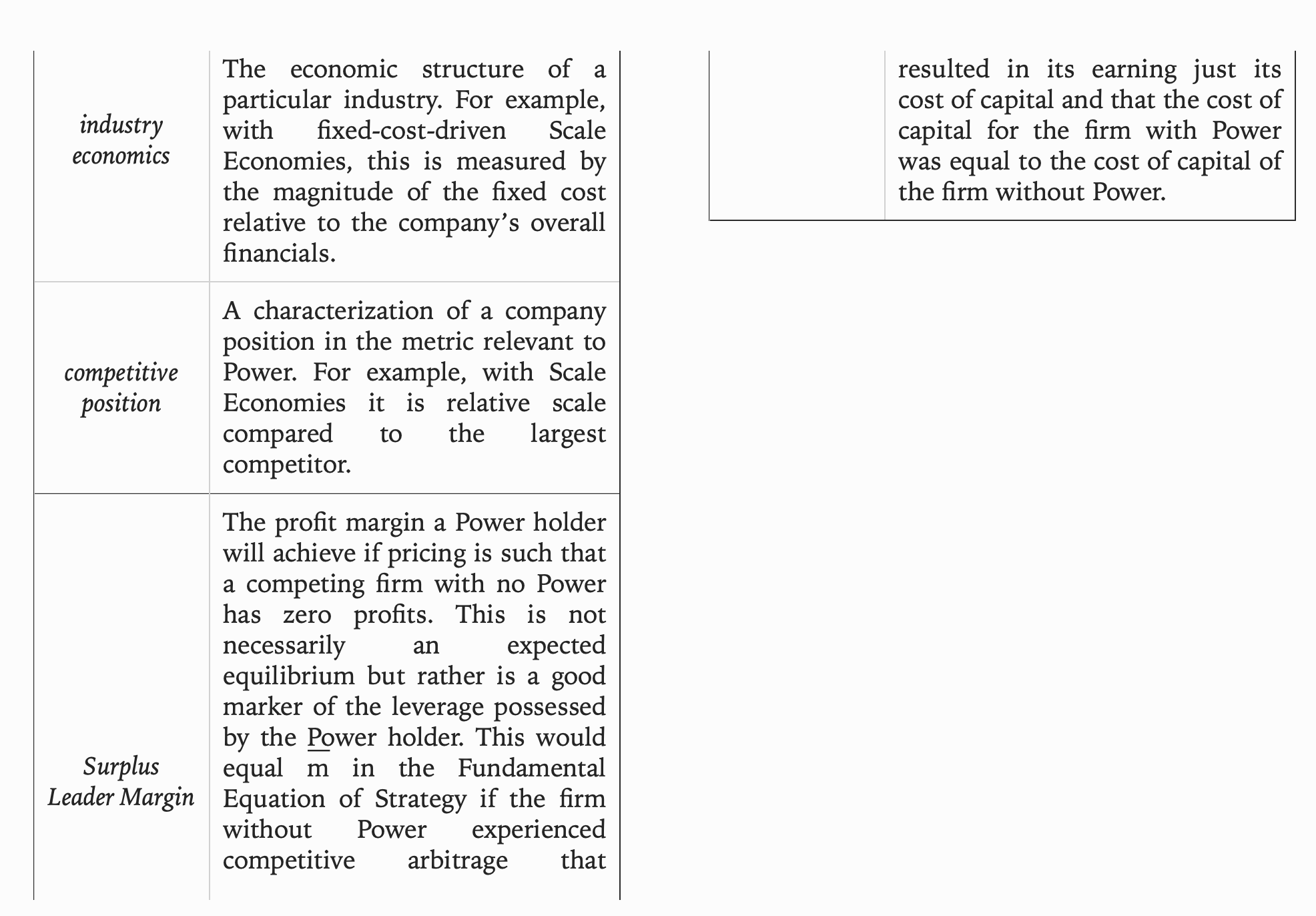

Industry Economics and Competitive Position: The conditions of Power involve the interaction between the underlying industry’s economics and the specific business’ competitive position.

-

Complex Competition: Power, unlike strength, is an explicitly relative concept: it is about your strength in relation to that of a specific competitor. Good strategy involves assessing Power with respect to each competitor, which includes potential as well as existing competitors, and functional as well as direct competitors. Any such players could be the source of the arbitrage you are trying to circumvent, and any one arbitrageur is enough to drive down differential margins

-

Leadership: The notion of Power (and the impact of its lack) is what underlies Warren Buffett’s view that if you combine a poor business with a good manager, it is not the business that loses its reputation. On the other hand, always the domain of Economists, I am a strong believer in the importance of leadership in the creation of value. Intel’s experience is again instructive. I have little doubt that the managerial acuity of Bob Noyce, Gordon Moore and Andy Grove would be remembered quite differently had they stuck with memories. True, but it is also true that their combined leadership was decisive in backing microprocessors in the first place and in a variety of choices that assured a route to continuing Power

SCALE ECONOMIES—the First of the 7 Powers

-

The quality of declining unit costs with increased business size is referred to as Scale Economies. It is the first of the 7 Powers

- Why do Scale Economies result in Power? Power is a configuration that creates the potential for persistent significant differential returns, even in the face of fully committed and competent competition. To fulfill this, two components must be simultaneously present:

- A Benefit: some condition which yields material improvement in the cash flow of the Power wielder via reduced cost, enhanced pricing and/or decreased investment requirements

- A Barrier: some obstacle which engenders in competitors an inability and/or unwillingness to engage in behaviors that might, over time, arbitrage out this benefit

-

For Scale Economies, the Benefit is straightforward: lowered costs. In the case of Netflix, their lead in subscribers translated directly in lower content costs per subscriber for originals and exclusives

-

The Barrier, however, is subtler. What prevents other firms from competing this away? The answer lies in the likely interplay of well-managed competitors. Suppose a company has a significant scale advantage in a Scale Economies business. Smaller firms would spot this advantage, and their first impulse might be to pick up market share, thus improving their relative cost position and erasing some of this disadvantage while improving their bottom line. To get there, however, they would have to offer up better value to customers, such as lower prices. In an established market, such tactics are visible to the leader, who would realize the threat of reducing their relative scale advantage; they would retaliate by using their superior cost position as a defensive redoubt (matching price cuts for example). After several bouts of this, a follower will come to expect such retaliation and build it into their financial models for the impact of gain-share moves. For them, such moves would inevitably destroy value, rather than create it

-

Intel’s microprocessor business is a good example of how this plays out. Intel developed Scale Economies in the microprocessor business. Over a very long period, they were doggedly challenged by Advanced Micro Devices in this space. The outcome: a continuingly great business for Intel and persistent pain for AMD—at every turn Intel could fight off AMD relying on the economics rooted in its Scale Economies

- Scale Economies: Benefit: Reduced Cost

-

Scale Economies: Barrier: Prohibitive Costs of Share Gains

- Beyond fixed costs, Scale Economies emerge from other sources as well. To name a few:

- Volume/area relationships: These occur when production costs are closely tied to area, while their utility is tied to volume, resulting in lower per-volume costs with increasing scale. Bulk milk tanks and warehouses would serve as examples

- Distribution network density: As the density of a distribution network increases to accommodate more customers per area, delivery costs decline as more economical route structures can be accommodated. A new entrant competitor to UPS would face this difficulty

- Learning economies: If learning leads to a benefit (reduced cost or improved deliverables) and is positively correlated with production levels, then a scale advantage accrues to the leader

- Purchasing economies: A larger scale buyer can often elicit better pricing for inputs. For example, this has helped Wal-Mart

-

A productive way to more formally calibrate the intensity of the scale leader’s Power is to assess the economic leeway they have in balancing attractive returns with appropriate retaliatory behavior to maintain share. The greater this leeway, the more attractive the longer-term equilibrium is likely to be for the leader. To do this, let me introduce the notion of Surplus Leader Margin (SLM). This is the profit margin the business with Power can expect to achieve if pricing is such that its competitor’s profits are zero

-

If the fixed cost = C, then: Surplus Leader Margin = [C/(Leader Sales)] * [(Leader Sales)/(Follower Sales) – 1]

-

The first term of this indicates the relative significance of fixed cost in the company’s overall financials, while the second term shows the degree of scale advantage. Put another way: Surplus Leader Margin = [Scale Economy Intensity] * [Scale Advantage]

-

The first term is tied to the economic structure of that industry (the intensity of the scale economy), a condition faced by all firms. The second term reflects the position of the leader relative to the follower. For Power to exist, both of these terms must be significantly positive

-

For example, even if there exists strong potential scale economies (C is large, relative to sales), the leader margin will still be zero (no Power) without any scale differential, because that second term was still zero, too

- This parsing of Power intensity into the separate strata of industry economics and competitive position is critical for a practitioner as it applies to most types of Power. In any assessment of Power, both need to be understood independently, and both are fair game for strategy initiatives

NETWORK ECONOMIES—the second of the 7 Powers

-

Network Economies definition: A business in which the value realized by a customer increases as the installed base increase

-

Recruiters want to make the best use of their time, so they go to the source with the largest number of listed professionals, while at the same time professionals want to list their names on the site with the most recruiters visiting. Such one-hand-shakes-the-other self-reinforcing upward spirals are known as Network Economies 22 : the value of the service to each customer is enhanced as new customers join the network

-

Why BranchOut failed? The success of all three parties on this dance card, BranchOut, Facebook and LinkedIn, was predicated on users’ value of the service depending on the presence of others, the central feature of Network Economies. Their founders were fully aware of this business characteristic and aggressively and competently pushed tactics fully consistent with this understanding. Facebook and LinkedIn could co-exist because their respective networks were walled off from one another: users wanted to keep their personal lives (Facebook) separate from their work lives (LinkedIn). BranchOut hoped to build a bridge between the two, but it just didn’t fly. Users wanted this wall maintained, a lesson Facebook themselves learned in their failed rollout of Facebook at Work

- Network Economies occur when the value of a product to a customer is increased by the use of the product by others. Returning to our Benefit/Barrier characterization of Power:

- Benefit: A company in a leadership position with Network Economies can charge higher prices than its competitors, because of the higher value as a result of more users. For example, the value of LinkedIn’s HR Solutions Suite comes from the numbers of LinkedIn users, so LinkedIn can charge more than a competiting product with fewer participants

- Barrier: The barrier for Network Economies is the unattractive cost/benefit of gaining share, and this can be extremely high. In particular the value deficit of a follower can be so large that the price discount needed to offset this is unthinkable. For example, “What would BranchOut have had to offer users for them to use BranchOut rather than LinkedIn?” I think most observers would agree that every user would have required a non-trivial payment, so the total spend for “BranchOut would have been colossal

- Industries exhibiting Network Economies often exhibit these attributes:

- Winner take all: Businesses with strong Network Economies are frequently characterized by a tipping point: once a single firm achieves a certain degree of leadership, then the other firms just throw in the towel. Game over—the P&L of a challenge would just be too ugly. For example, even a company as competent and with as deep pockets as Google could not unseat Facebook with Google+

- Boundedness: As powerful as this Barrier is, it is bounded by the character of the network, something well-demonstrated by the continued success of both Facebook and LinkedIn. Facebook has powerful Network Economies itself but these have to do with personal not professional interactions. The boundaries of the network effects determine the boundaries of the business

- Decisive early product. Due to tipping point dynamics, early relative scaling is critical in developing Power. Who scales the fastest is often determined by who gets the product most right early on. Facebook’s trumping of MySpace is a good example

-

Power insures the ability to earn outsized returns well into the future, driving up value. This is captured by the Benefit/Barrier requirement. Lets use Surplus Leader Margin to calibrate the intensity of Power: “What governs the leader’s profitability when prices are such that the challenger makes no profit at all?”

-

In the case of Network Economies, assume all costs are variable (c), so the challenger’s profit is zero when the price equals these variable costs. The value the leader offers is greater than this by the differential network benefits it offers, and lets assume they can bump up price to account for this Surplus Leader Margin 24 = 1 – 1/[1+δ(S N – W N)] Where δ ≡ the benefit which accrues to each existing network member when one more member joins the network divided by the variable cost per unit of production SN ≡ the installed base of the leader & WN ≡ the installed base of the follower. δ is a measure of the intensity of Network Economies: how important the network effect is relative to industry costs. This formula is of course stylized. This formula is of course stylized. In a real world situation like that faced by BranchOut, LinkedIn and Facebook, the value of the benefit of others on the network is more complex. For example, it would not be expected to be strictly linear: if you are a US college student on Facebook, another user in Ulan Bator is likely to be of far less value to you than the presence of one of your classmates

-

It was the hope of Marini and his investors that the δ of BranchOut would be driven by the absolute installed base leadership of Facebook rather than keyed to the more narrowly defined “professional” space installed base of BranchOut. It turned out that there was very little spillover. This meant that LinkedIn had an insurmountable advantage in this space

-

[S N – W N] is the leader’s absolute advantage in installed base. As you would expect, as this approaches zero, the Surplus Leader Margin also approaches zero, even if the industry has strong Network Economies. This equation also makes evident the tipping point outcome of Network Economies. As the installed base difference gets large, the pricing such that the follower has zero profits results in very large leader margins (100% at the limit). This means a leader can price at very attractive margins while still pricing well below the breakeven point for the follower. The result is that a follower would have to price at a significant loss to offer equivalent value. As pointed out earlier, in BranchOut’s case it would not surprise me if users would have had to be paid (a negative price) to switch from LinkedIn

-

We have parsed the intensity of a Power type into separate components: one reflecting industry economics (δ, the degree to which network economies exist in a particular business) and the other competitive position ( [S N – W N] ) within that structure

- More comments on Network Economies:

- There can be positive network effects but no potential for Power

- The network effect δ needs to be large enough relative to the potential installed base and the cost structure for there even to be one profitable player as this fulfills the Benefit condition. If homogeneous network effects are the only value source, then if N δ < c, a firm cannot reach profitability

- This is the problem often in Silicon Valley. If one supposes Network Economies then the strategy imperative is to scale much faster than anyone else—if another firm gets to the tipping point before you, then the game is over

- However, ex ante it is often very difficult to have much assurance in sizing potential N and δ. So you are left with a situation that sometimes requires significant up front capital but an uncertain ability to monetize. This for example has plagued Twitter. Usually management gets the blame but we are back to Buffett’s observation: “When a manager with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, the reputation of the business remains intact

- Network effects can be very complex. As indicated “As indicated earlier, however, there are many excellent treatments so I have been brief. A common twist I have not covered are indirect network effects (also called demand side network effects).

- If a business has important complements and these complements are somehow exclusive to each offering, then a leader will attract more and/or better complements

- As a result the entire value proposition to a customer is improved (increasing SLM for example). An example of this would be smartphone apps. Another smartphone OS would be hard to offer at this point because it would start out with a dearth of apps. This would make it very unattractive. Developers of apps would of course not be incented to spend their scarce resources since the market would be small

- Note that in this case the contribution of additional complements is not linear

COUNTER POSITIONING —the third of the 7 Powers

-

Counter-Positioning: A newcomer adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business

-

Counter-Positioning: the Benefit and Barrier: There are few occurences in business as complex as the emergence and eventual success of a new business model. Think of the diverse circumstances attending Vanguard’s rise: huge and successful incumbent active mutual funds, a committed entrepreneur, an advancing intellectual frontier, fast-improving computer technology, entrenched channel disincentives, consumer misinformation, and so on. In situations like this, it falls to the strategist to carefully peel back the layers of complexity and eventually seize upon some irreduceable kernel of insight amidst the competitive reality

- To understand the ascendancy of Vanguard, I must first note these characteristics:

- An upstart who developed a superior, heterodox business model

- That business model’s ability to successfully challenge well-entrenched and formidable incumbents

- The steady accumulation of customers, all while the incumbent remains seemingly paralyzed and unable to respond

- Returning to our Benefit/Barrier characterization of Power:

- Benefit: The new business model is superior to the incumbent’s model due to lower costs and/or the ability to charge higher prices. In Vanguard’s case, their business model resulted in substantially lower costs (the elimination of expensive portfolio managers, as well as the reduction of channel costs and unnecessary trading costs) which then translated into superior product deliverables (higher average net returns). Due to their business structure of returning profits to their fund-holders, they realized value from market share gains (s in the fundamental equation of strategy), rather than ramping up differential profit margins (m)

- Barrier: The barrier for Counter-Positioning seems a bit mysterious: how could a powerhouse (such as Fidelity Investments in this case) allow itself to be persistently humbled by an upstart over such an extended period? Couldn’t they foresee the potential success of Vanguard’s model? Frequently in such situations, naïve onlookers castigate the incumbent for lack of vision, or even just poor management. Often, too, they level this accusation at companies with prior plaudits for business acumen. In many cases, this view is unjust and misleading. The incumbent’s failure to respond, more often than not, results from thoughtful calculation. They observe the upstart’s new model, and ask, “Am I better off staying the course, or adopting the new model?” Counter-Positioning applies to the subset of cases in which the expected damage to the existing business elicits a “no” answer from the incumbent. The Barrier, simply put, is collateral damage. In the Vanguard case, Fidelity looked at their highly attractive active management franchise and concluded that the new passive funds’ more modest returns would likely fail to offset the damage done by a migration from their flagship products

-

The Varieties of Collateral Damage: There can be several possible reasons for the incumbent’s failure to mimic the upstart. In this section I will detail those differences, as knowing them will clarify the correct strategic posture. Here’s a useful way to visualize this: imagine the incumbent CEO’s business development team must evaluate the prudence of investing in the challenger’s new approach. Stand-Alone Unattractive is Not Counter-Positioning . In its first step, the business development team would hive off those situations in which a stand-alone assessment of the new approach forecasts an unattractive return, as these are not Counter-Positioning. To this end, the team would pose this question: “If “No” is the answer, then collateral damage does not account for the incumbent’s rejection of the challenger’s approach to the business. The new approach is simply a poor bet all by itself. Here the example of the digital camera challenge to Kodak is instructive. Kodak’s business model was legendary, built on the customer’s continuing need to purchase film, a product in which Kodak was wildly profitable due to both Scale Economies and a proprietary edge (this Power type is Cornered Resources, to be covered in Chapter 6). Kodak offered the first of its path-breaking Brownie cameras in 1900. By 1930 it was one of the firms in the Dow Jones Industrial index, and it stayed in that group for more than 40 years—one of the great business empires. Until digital photography came along, that is. Anyone could extrapolate from Moore’s Law that analog chemical film was eventually doomed. Pundits have looked back and chided Kodak for poor management, lack of vision, and organizational inertia, and a reasonable person might well ask, “How could a company high on the lists of the best companies in the world succumb to such a defeat?” A reasonable question. And the answer is much simpler than many suggest: in fact, Kodak was fully aware of its eventual fate and spent lavishly to explore survival options, but digital photography simply was not an attractive business opportunity for the company. Kodak’s business model was built on its Power in film—it was not a camera company. The digital substitute for film was semiconductor storage, and Kodak brought nothing to this arena. As a company, Kodak had excellent management; thus the observed wheel-spinning, their fruitless explorations in the digital world, simply reflected the strategic cul-de-sac they faced. The technological frontier had moved: consumers were better off, but Kodak was not

- More generally this situation can be characterized by three conditions:

- A new superior approach is developed (lower costs and/or improved features)

- The products from the new approach exhibit a high degree of substitutability for the products from the old approach. In this case, as semiconductor topologies shrunk, digital imaging came to completely supplant chemical imaging

- The incumbent has little prospect for Power in this new business: either the industry economics support no Power “commodity), or the incumbent’s competitive position is such that attainment of Power is unlikely. Kodak’s formidable strengths had little relevance to semiconductor memory, and those new products were on an inevitable path to commodization

-

Counter-Positioning versus Disruptive Technologies: At the heart of Counter-Positioning lies the development of a new business model that, over time, has the potential to supplant the old. In the more general sense of the word, it is disruptive. However, when we consider the more specific meaning of Disruptive Technologies (DT) developed by Christensen, the waters muddy

- Consider these examples:

- Kodak vs. digital photography. This is a DT, but not CP

- In-N-Out vs. McDonald’s. This is CP, but not DT (no new technology involved)

- Netflix streaming vs. HBO via cable. This is both CP and DT

-

Observations on Counter-Positioning: Before wrapping up this chapter, I want to offer up a few observations about Counter-Positioning that will be specifically useful to a strategist. As noted in the Introduction, Power must be considered relative to each competitor, actual and implicit. With Counter-Positioning, this is particulary important, because this type of Power only applies relative to the incumbent and says nothing regarding Power relative to other firms utilizing the new business model. So it remains only a partial strategy. To assure value creation, it must be complemented by a route to Power respective to other like competitors. For example, In-N-Out has Counter-Positioning Power over McDonald’s, but this helps them not at all in facing like competitors such as Five Guys Burgers and Fries. As noted in our discussion of the collateral damage types, Cognitive Bias can play a role in deterring the incumbent. But the challenger, by its posture, may be able to influence such a move. How to attempt this? In its ascendancy, the challenger should avoid the temptation of trumpeting its superiority, instead suppressing that urge and adopting a tone of respect toward the incumbent. This behavior may result in the incumbent delaying objective cognition, giving the challenger a headstart on the new business model.

-

Counter-Positioning is not an exclusive source of Power. The two prior chapters covered Power types that were exclusive: there could be only one company with Power. This is a reflection of the “Competitor Position” portion of the leverage calculation I have detailed. For these earlier types, there can be only one firm with a favorable competitive position. In contrast, there could be—and often are, in fact—many challengers Counter-Positioned respective to the incumbent. A Counter-Positioning challenge is one of the toughest management challenges. When I started teaching at Stanford in 2008, Nokia was the leader in smartphones. By 2014 they had disappeared from this market

-

Though this isn’t always the case, I have noticed a frequently repeated script for how an incumbent reacts to a CP challenge. I whimsically refer to it as the Five Stages of Counter-Positioning: Denial, Ridicule, Fear, Anger, Capitulation (frequently too late)

-

Once market erosion becomes severe, a Counter-Positioned incumbent comes under tremendous pressure to do something; at the same time, they face great pressure to not upset the apple cart of the legacy business model. A frequent outcome of this duality? Let’s call it dabbling: the incumbent puts a toe in the water, somehow, but refuses to commit in a way that meaningfully answers the challenge

- Counter-Positioning often underlies situations in which the following developments are jointly observed:

- For the challenger

- Rapid share gains

- Strong profitability (or at least the promise of it)

- For the incumbent

- Share loss

- Inability to counter the entrant’s moves

- Eventual management shake-up(s)

- Capitulation, often occuring too late

- For the challenger

-

The Challenger’s Advantage: An entrenched incumbent with established Power is formidable—this is axiomatic. Unless the incumbent is incompetent over an extended period of time, challenging it is most often a loser’s game, and playing that game is no fun—AMD’s long and enervating battle to emerge from the shadow of Intel yields a case in point. That said, there are fighting styles which turn the contest on its head by converting strength into weakness. Think of Muhammed Ali’s defeat of the intimidating George Foreman with his improvised Rope-A-Dope: Ali relied on Foreman’s straight-ahead style and confidence to lure him into strength-sapping flurries. Such reversals are rare in business, because contests typically take place over extended periods and with great thoughtfulness on all sides. Even a momentary lapse by an incumbent won’t present a sufficient opening. The only bet worthwhile for a challenger is one in which even if the incumbent plays its best game, it can be taken off the board. A competent Counter-Positioned challenger must take advantage of the strengths of the incumbent, as it is this strength which molds the Barrier, collateral damage

- Counter-Positioning Leverage: For Counter-Positioning, the Competitor Position element of Power is simply binary: you have adopted the heterodox business model. The Industry Economics aspect of Power refers to the central characteristics of this model: it must be superior, and it must cause the expectation of perceived collateral damage

SWITCHING COSTS/ ADDICTION —the fourth of the 7 Powers

-

Switching Costs definition: The value loss expected by a customer that would be incurred from switching to an alternate supplier for additional purchases

-

Switching Costs arise when a consumer values compatibility across multiple purchases from a specific firm over time. These can include repeat purchases of the same product or purchases of complementary goods

-

Benefit: A company that has embedded Switching Costs for its current customers can charge higher prices than competitors for equivalent products or services. This benefit only accrues to the Power holder in selling follow-on products to their current customers; they hold no Benefit with potential customers and there is no Benefit if there are no follow-on products

-

Barrier: To offer an equivalent product, competitors must compensate customers for Switching Costs. The firm that has previously roped in the customer, then, can set or adjust prices in a way that puts their potential rival at a cost disadvantage, rendering such a challenge distinctly unattractive. Thus, as with Scale Economies and Network Economies, the Barrier arises from the unattractive cost/benefit of share gains for the challenger

- Switching Costs can be divided into three broad groups:

- Financial: Financial Switching Costs include those which are transparently monetary from the outset. For ERP, these would include the purchase of both a new database and the sum total of its complementary applications

- Procedural: Procedural Switching Costs are somewhat murkier but no less persuasive. They stem from the loss of familiarity with the product or from the the risk and uncertainty associated with the adoption of a new product. When employees have invested time and effort to learn the particulars of how to use a certain product, there can be a significant cost to retraining them in a different system. In the case of SAP, applications exist for a wide array of enterprise functions. This means that there are employees in human resources, sales and marketing, procurement, accounting, not to mention managers across these many divisions, who have all learned how to create reports based on the SAP system and its complementary software. Such a system-switch breeds organizational discontent by forcing many within the ranks of the organization to change their daily routines. Furthermore, procedural changes open the door for errors. With databases, these are particularly costly, since they involve the totality of the customer’s information. Even when a competitor provides services and programs to help mitigate such difficulties of transition, these often prove costly and imperfect

- Relational: Relational Switching Costs are those tolls which would result from the breaking of emotional bonds built up through use of the product and through interactions with other users and service providers. Often a customer establishes close, beneficial relationships with the provider’s sales and service teams. Such familiarity, ease of communication and mutual positive feelings can create resistance to the prospect of severing those ties and switching to another vendor. Additionally, if the customer has developed affection for the product and their identity as a user, or if they enjoy the camaraderie which exists amongst a community of like users, they may shrink from the prospect of switching identities and abandoning that community

-

Switching Costs Multipliers: Switching Costs are a non-exclusive Power type: all players can enjoy their benefits. IBM and Oracle are competitors to SAP, and they also benefit from high customer retention rates and Switching Costs. As a market matures, the Benefit of Switching Costs becomes transparent to all players and they are able to calculate the value of an acquired customer. More often than not this leads to enhanced competition to grab new customers, which arbitrages out the Benefit for new customer acquisitions. So the major value contribution comes from capturing customers before such value-destroying pricing arbitrage transpires. Switching Costs offer no Benefit if no additional related sales are made to the customer. To assure that such additional sales take place, one tactic might be to develop more and more add-on products. This has been SAP’s tack. “cquisitions significantly accelerate product line extensions, too, serving as a sort of outsourced development. This too has been part of SAP’s playbook, as proven by their ambitious acquisition program. The building of such product portfolios can serve to boost all three categories of Switching Costs. Not only does it extend the revenue coverage of the Switching Costs (Financial), but it often increases their intensity by making the prospect of disentanglement more and more forbidding (Procedural). A high level of integration into customer operations, and the extensive training that demands, can also further disincentivize such disentanglement. This sort of training also has the potential of building emotional bonds to the current supplier (Relational)

-

Switching Costs: Industry Economics and Competitive Position: As noted before, Switching Costs are a non-exclusive Power: their benefits are available to all players. So the intensity of Switching Costs derives from “Industry Economics,” those conditions faced equally by all players. The potential benefits accrue only if you have a customer, so the competitive position component of Switching Costs is binary: you either have the customer, or you do not

- I should note that such advantages can be swept away by tectonic shifts in technology. ERP firms know well this lesson; that’s why SAP and Oracle are presently doing their best to make certain they are not leapfrogged by cloud-based applications. Importantly, too, Switching Costs can pave the path for other Powers as well. Connecting users and building a large supply of complementary goods may generate Network Effects. Or if the product preference of users already tethered by Switching Costs spills over to a wider pool of potential customers, you could find yourself enjoying the effects of Branding

BRANDING FEELING GOOD —the fifth of the 7 Powers

-

Branding definition: The durable attribution of higher value to an objectively identical offering that arises from historical information about the seller

-

In 2005, Good Morning America purchased a diamond ring at Tiffany & Co. for $16,600 and one of similar size and cut at Costco for $6,600. They then asked Martin Fuller, a reputable gemologist and appraiser, to assess the rings’ values. Fuller assessed the Costco ring at $8,000 plus setting costs, more than $2,000 above the selling price. “It’s a little bit of a surprise. You wouldn’t normally consider a fine diamond to be found in a general store like Costco….” 49 Fuller assessed the Tiffany ring at $10,500 plus setting costs at a non-brand-name retailer. The result is hardly idiosyncratic. Compared to the more generic Blue Nile online offering, Tiffany’s prices are nearly double

-

The brand has become a standard for wealth and luxury. Over this long history, Tiffany has carefully curated its image. Packaging provides a famous case in point

-

Tiffany’s website touts the message conveyed by its signature Blue Box: Glimpsed on a busy street or resting in the palm of a hand, Tiffany Blue Boxes make hearts beat faster and epitomize Tiffany’s great heritage of elegance, exclusivity and flawless craftsmanship

- This wording is hardly casual:

- “Heritage” implies a long and positive history of doing the same thing (in this case, creating elegant, exclusive and flawless jewelry)

- “Elegance” designates a particular aesthetic design which consumers can consistently expect from the product despite repeated changes in lead designers and collections

- “Exclusivity” hints that the Tiffany product can only be attained by those willing to pay for the very best. It also suggests that only Tiffany, and no competitor, can provide this type of craftsmanship

- “Flawless” assures the customer that over this long history Tiffany has repeatedly created perfect products, meaning buyers face no uncertainty as to the quality of the jewelry

- “Tiffany’s success is evidenced by the fact that, although the Blue Box comes free with a purchase, it carries a standalone monetary value.”

-

Tiffany’s pricing advantage drives strong differential margins (in the Fundamental Equation of Strategy)

-

Tiffany’s Power lies in Branding. Branding is an asset that communicates information and evokes positive emotions in the customer, leading to an increased willingness to pay for the product

- Benefit: A business with Branding is able to charge a higher price for its offering due to one or both of these two reasons:

- Affective valence: The built-up associations with the brand elicit good feelings about the offering, distinct from the objective value of the good. For example, Safeway’s cola may be indistinguishable from Coke’s in a blind taste test, but even after revealing the result, the taste tester remains willing to pay more for Coke

- Uncertainty reduction: A customer attains “peace of mind” knowing that the branded product will be as just as expected. Consider another example: Bayer aspirin. Search for aspirin on Amazon.com and you will see a 200 count of Bayer 325 mg. aspirin for $9.47 side-by-side with a 500 count of Kirkland 325 mg. aspirin for $10.93. So Bayer has a price per tablet premium of 117%. Some customers still would prefer the Bayer because of diminished uncertainty: “Bayer’s long history of consistency makes customers more confident that they are getting exactly what they want. Note that the Benefit from Branding does not depend on prior ownership, as with Switching Costs

-

Barrier: A strong brand can only be created over a lengthy period of reinforcing actions (hysteresis ), which itself serves as the key Barrier. Again, Tiffany has cultivated its brand name for more than a century. What’s more, copycats face daunting uncertainty in initiating Branding: a long investment runway with no assurance of an eventual path to significant affective valence. Efforts to mimic another brand run the risk of trademark infringement actions as well with their attendant costs and unclear outcomes

- Branding—Challenges and Characteristics:

- Brand Dilution: Firms require focus and diligence to guide Branding over time and ensure that the reputation created remains consistent in the valences it generates. Hence, the biggest pitfall lies in diminishing the brand by releasing products which deviate from, or damage, the brand image

- Seeking higher “down market” volumes can reduce affective valence by damaging the aura of exclusivity, weakening positive associations with the product. For example, Halston rose to fame in the 1970s as a high-end design standard for women’s clothing. However, when Halston accepted $1 billion from lower-end retailer J.C. Penney to expand into affordable fashion lines for the mass consumer, Bergdorf Goodman dropped the label in order to protect their brand. The J.C. Penney line was a failure, and the Halston name never recaptured its previously enviable Branding

- I stated earlier that Branding’s Barrier is hysteresis and uncertainty. Dilution threatens Branding Power because it can “reset the hysteresis clock,” forcing a company to restart the slow and uncertain process of building affective valence. The Halston experience serves as a persuasive case in point

- Counterfeiting: Since it is the label, not the product, that bestows Branding Power, counterfeiters may try to free-ride by falsely associating a powerful brand with their product. Because Branding relies upon repeated positive interactions with consumers, counterfeiters who flood the market with inconsistent offerings can gradually undermine it. For instance, in 2013 Tiffany sued Costco for intimating to shoppers that they sold Tiffany jewelery; the company had previously sued eBay for facilitating the sale of counterfeits. A press release to investors after the filing of the 2013 suit explicitly noted that, “Tiffany has never sold nor would it ever sell its fine jewelry through an off-price warehouse retailer like Costco.”

- Changing consumer preferences: Over time, customer preferences may vary in a way that undermines the value of Branding. Nintendo developed a brand for family-friendly video games. However, as the gaming demographic evolved from predominantly children to adults, there was a shift in demand for more mature games. Nintendo’s Branding did not extend to this segment with the attendant negative impact. In terms of the Fundamental Equation of Strategy, the attractive differential margins (m ) achieved in the M0 of the children’s segment would elude Nintendo in the adult segment. 54 Problem is, the qualities that make Branding a Power also make it hard to change; the considerable risk is dilution or brand destruction

- Geographic boundaries: The affective valence may apply in one region but not another. For example, for many years, Sony enjoyed a Branding advantage with its televisions in the United States. In Japan, however, it enjoyed no such advantage, thus preventing it from enjoying premium pricing over rivals such as Panasonic

- Narrowness: To clear the high hurdle of Power, Branding in the context of Power Dynamics is a much more restricted concept than in marketing. For example, even if “brand recognition” is very high, there may not be Branding Power. In instances like this, it could actually be Scale Economies creating heightened brand awareness. For example, Coca Cola can sponsor Super Bowl ads while RC Crown Cola cannot because the ad cost is only justifiable for an entity of Coca Cola’s size. A strategist would gravely err in classifying this as Branding. RC could make all the right Branding moves and still be at the same disadvantage due to relative scale

- Non-exclusivity: Note that Branding is a non-exclusive type of Power. Indeed, a direct competitor might have an equally impactful brand that targets the same customers (e.g., Prada and Luis Vuitton and Hermès). All competitors with brand Power, however, still will earn returns superior to those of the competitor with no Branding

- Type of Good: Only certain types of goods have Branding potential as they must clear two conditions:

- Magnitude: the promise of eventually justifying a significant price premium. Business-to-business goods typically fail to exhibit meaningful affective valence price premia, since most purchasers are only concerned with objective deliverables. Consumer goods, in particular those associated with a sense of identity, tend to have the purchasing decision more driven by affective valence. Here’s the reason: in order to associate with an identity, there must be some way to signal the exclusion of alternative identities. For Branding Power derived from uncertainty reduction, the customer’s higher willingness to pay is driven by high perceived costs of uncertainty relative to the cost of the good. Such products tend to be those associated with bad tail events: safety, medicine, food, transport, etc. Branded medicine formulations, for example, are identical to those of generics, yet garner a significantly higher price

- Duration: a long enough amount of time to achieve such magnitude. If the requisite duration is not present, the Benefit attained will fall prey to normal arbitraging behavior

- Branding: Industry Economics and Competitive Position: In the case of Branding, I assume all costs are marginal, so the zero challenger profit price equals marginal costs. The value the leader offers is greater than this by the brand value it offers, and I assume they can charge a higher price. As a consequence: S Margin = 1 – 1/B(t) where B(t) ≡ brand value as a multiple of the weaker firm’s price, t ≡ units of time since the initial investment in brand. Industry economics define the function B(t) and determine the magnitude and sustainability of leverage. Time t represents the competitive position that S has relative to W in developing brand power

CORNERED RESOURCE —the sixth of the 7 Powers

-

Cornered Resource definition: Preferential access at attractive terms to a coveted asset that can independently enhance value

-

Benefit: In the Pixar case, this resource produced an uncommonly appealing product—“superior deliverables”—driving demand with very attractive price/volume combinations in the form of huge box office returns. No doubt—this was material (a large m in the Fundamental Equation of Strategy). In other instances, however, the Cornered Resource can emerge in varied forms, offering uniquely different benefits. It might, for example, be preferential access to a valuable patent, such as that for a blockbuster drug; a required input, such as a cement producer’s ownership of a nearby limestone source, or a cost-saving production manufacturing approach, such as Bausch and Lomb’s spin casting technology for soft contact lenses

-

Barrier: The Barrier in Cornered Resource is unlike anything we have encountered before. You might wonder: “Why does Pixar retain the Brain Trust?” Any one of this group would be highly sought after by other animated film companies, and yet over this period, and no doubt into the future, they have stayed with Pixar. Even during the company’s rocky beginning, there was a loyalty that went beyond simple financial calculation. To illustrate: in 1988, long before Disney began its association with Pixar, Lasseter won an Academy Award for “for his Pixar short Tin Toy, prompting Disney CEO Michael Eisner and Disney Chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg to try to recruit their former employee back into the Disney fold. Lasseter demurred: “I can go to Disney and be a director, or I can stay here and make history.” 59 So in Pixar’s case, the Barrier was personal choice. In the case of spin casting technology, it is patent law, and in the case of cement inputs, it is property rights. Our general term for this sort of barrier is “fiat”; it is not based on ongoing interaction but rather comes by decree, either general or personal. In a case of the cart driving the “donkey, it was Lasseter’s commitment to Pixar that helped convince Katzenberg to do the three-picture deal with Pixar in 1991. Likewise, Disney’s later CEO, Bob Iger, would decide to acquire Pixar only after realizing such an acquisition would be the sole means of bringing Pixar’s talent to Disney’s flagging animation group. The subsequent revival of Disney Animation affirmed his wisdom

- The Five Tests of a Cornered Resource:

- The Power hurdle is high: to qualify, an attribute must be sufficiently potent to drive high-potential, persistent differential margins (m » 0), with operational excellence spanning the gap between potential and actual. With an enterprise like Pixar, there are numerous resources critical to success, and sorting through this multiplicy to try to isolate the Power source can be a challenge. Over the years I have found that five screening tests for a Cornered Resource often help in this process

- Idiosyncratic: If a firm repeatedly acquires coveted assets at attractive terms, then the proper strategy question is, “Why are they able to do this?” For example, if one discovered that Exxon was able to persistently gain the rights to desirable “hydrocarbon properties, then understanding their path to access would be the more crux issue. Perhaps their relative scale allows them to develop better discovery processes? If so, their discovery processes are the Cornered Resource, the true source of Power, and it would be misleading to simply cite only the acquired leases. Examining the Pixar Brain Trust through this lens, then, proves highly informative. In particular, you might notice one striking aspect of the Brain Trust: it is largely restricted to a specific set of individuals. As a first indication, consider that every one of their first eleven films was directed by one of this group (except for Brad Bird, discussed below). Further, Pixar’s record shows that simple inclusion into the group will not preternaturally endow newbie directors with the “Brain Trust process.” Such directors frequently fail, as evidenced by the replacement of Ash and Colin Brady on Toy Story 2, Jan Pinkava on Ratatouille and Brenda Chapman on Brave. I believe the Brain Trust is more than a combination of individual talents; rather it is the foundational members’ shared experience in the early trial years that has yielded one success after another. If, indeed, we observed new directors being brought into the fold and achieving Pixar-level commercial and artistic success, then we could conclude that Power came not from the Brain Trust but instead from some deeper current. From this assessment, I have come to believe that the most important strategic challenge for Pixar is renewal of its director pool. An informed observer might ask about Brad Bird, who masterminded several of Pixar’s biggest successes, coming into the studio and directing The Incredibles based on a screenplay he had previously developed outside the purview of the Brain Trust, and later stepping in to rescue Ratatouille . Wouldn’t he exemplify the sort of untested “outsider” director mentioned above? In fact, not really. On closer inspection, Brad Bird fits the assessment of the restricted nature of the Brain Trust. A classmate and friend of Lasseter from CalArts, Bird already shared a creative shorthand with many of the central figures of the Brain Trust. More, he was an accomplished and established animated film director upon his arrival at Pixar, as demonstrated by his fine film The Iron Giant

- Non-arbitraged: What if a firm gains preferential access to a coveted resource, but then pays a price that fully arbitrages out the rents attributable to this resource? In this case, it fails the differential return test of Power. Consider movie stars. A turn by Brad Pitt would probably advance box office prospects, therefore proving “coveted,” but his compensation captures much or all of this additional value and so fails the Power test. Likewise, although the Pixar Brain Trust is highly compensated, the amounts do not come close to matching their value. I was an investor in Pixar when it was public, and I realized a very nice return over the life of my investment, until the Disney acquisition

- Transferable: If a resource creates value at a single company but would fail to do so at other companies, then isolating that resource as the source of Power would entail overlooking some other essential complement beyond operational excellence. The word “coveted” in the definition conveys the expectation by many that the asset will create value. In the lead-up to his acquisition of Pixar, Bob Iger had an epiphany: the legacy of Disney’s animated characters formed the core of the corporation, and only the Pixar team could revive that legacy. This motivated his purchase of Pixar, as well as his decision to place Catmull and Lasseter at the helm of Disney Animation, which resulted in the meteoric revival of that storied division. Such a comeback would never have been possible without Catmull and Lasseter in key decision-making roles, and the Brain Trust on call, and it ultimately vindicated the steep price paid by Disney. This resource was transferable

- Ongoing: In searching for Power, a strategist tries to isolate a causal factor that explains continued differential returns. There’s a contrapositive to this, too: one would then expect differential returns to suffer should the identified factor be taken away. Clearly this perspective has bearing on the identification of a Cornered Resource. There may be many factors that proved formative in developing Power but whose contributions then became embedded in the business. For example, Post-it notes emerged as a highly profitable business for 3M only because Dr. Spenser Silver tirelessly sought commercial application for his not-so-sticky glue. Once the Post-It application was established, the business’ differential returns were not predicated on him and his unique glue, but rather a different—in part, at least—Cornered Resource: U.S. Patent 3,691,140. U.S. Patent 5,194,299 and the Post-It Trademark. At Pixar, Steve Jobs offered a similar case in point. He was essential to Pixar’s ascendancy—viewing him simply as patient money utterly understates his contribution—but his importance diminished as Pixar developed, and eventually his value became embedded in the company to the point where his continued presence was no longer needed to drive differential returns. The Brain Trust, on the other hand, endures as the sustaining force behind their success.

- Sufficient: The final Cornered Resource test concerns completeness: for a resource to “qualify as Power, it must be sufficient for continued differential returns, assuming operational excellence

-

Frequently, as I have observed, many will mistake specific leadership for a Cornered Resource; in fact, it fails this sufficiency test. For example, I am a fan of the abilities of George Fisher. He did a fine job leading Motorola. When he took the helm at Kodak, there were high hopes that his presence would lead to a revival of the company—i.e. that he was a Cornered Resource. The rough patch that followed was, in my view, not his fault; it was merely an indication of the hopeless cul-de-sac created by the company’s focus on chemical film in a solid-state age. These difficulties, however, yield an insight: Fisher was not a Cornered Resource, and the Motorola success involved other complements to his talent that were not later present at Kodak

- Another way to put this is that a Cornered Resource is a sufficient condition for potential for differential returns. In my view, current evidence best supports the assertion that the Pixar Brain Trust as a unit is the company’s Cornered Resource, as opposed to individual members, such as Catmull or Lasseter. “One might view Lasseter + Catmull together as the real Cornered Resource and then suggest that the other Brain Trust hires serve merely as a reflection of their selection skills. You could even view the revival of Disney Animation under Lasseter’s and Catmull’s leadership as evidentiary to this view. The failure of newbie Pixar directors, however, tends to belie this

PROCESS POWER -the seventh of the 7 Powers

-

Process Power: Embedded company organization and activity sets which enable lower costs and/or superior product, and which can be matched only by an extended commitment

-

Benefit: A company with Process Power is able to improve product attributes and/or lower costs as a result of process improvements embedded within the organization. For example, Toyota has maintained the quality increases and cost reductions of the TPS over a span of decades; these assets do not disappear as new workers are brought in and older workers retire

- Barrier: The Barrier in Process Power is hysteresis: these process advances are difficult to replicate, and can only be achieved over a long time period of sustained evolutionary advance. This inherent speed limit in achieving the Benefit results from two factors:

- Complexity: Returning to our example: automobile production, combined with all the logistic chains which support it, entails enormous complexity. If process improvements touch many parts of these chains, as they did with Toyota, then achieving them quickly will prove challenging, if not impossible

- Opacity: The development of TPS should tip us off to the long time constant inevitably faced by would-be imitators. The system was fashioned from the bottom up, over decades of trial and error. The fundamental tenets were never formally codified, and much of the organizational knowledge remained tacit, rather than explicit. “ It would not be an exaggeration to say that even Toyota did not have a full, top-down understanding of what they had created—it took fully fifteen years, for instance, before they were able to transfer TPS to their suppliers. GM’s experience with NUMMI also implies the tacit character of this knowledge: even when Toyota wanted to illuminate their work processes, they could not entirely do so

-

Strategy versus Operational Excellence. Professor Michael Porter of Harvard created quite a stir with his long-ago insistence that operational excellence is not strategy. 70 His reason for doing so, however, completely aligns with the “No Arbitrage” assumption of this book: improvements that can be readily mimicked are not strategic, because they do not contribute to increasing m or s in the Fundamental Equation of Strategy, as these are long-term equilibrium values

-

But wait a minute. Aren’t the step-by-step improvements that drive Process Power exactly what much operational excellence is all about? Yes, they are, but this represents only the Benefit side, which brings us to an important point of caution about Process Power. The type of Benefit it cites—evolutionary bottom-up improvement—stands at the heart of operational excellence; as such, it is quite common. The rarity of Process Power results from the infrequency of the Barrier: an unyielding, long-time constant for the improvements in question. No matter how much you invest or how hard you try, the desired improvements are constrained by a boundary of potential that is tied to time, as seen in the NUMMI experience of GM. Perhaps the best way to think of it is this: Process Power equals operational excellence, plus hysteresis. Having said that, such hysteresis occurs so rarely that I am in strong agreement with Professor Porter’s sentiments

- If one were to adopt a different definition of Strategy—something like “everything that is important”—then operational excellence would be strategic. “As is, though, operational excellence—while important, hard to achieve and worthy of management mind share—is not sufficient to gain competitive advantage

Netflix Case Study

- When I became an investor in Netflix in 2003, my investment hypothesis had two legs:

- Netflix’s DVD-rental business had Power: Counter-Positioning to the brick-and-mortar incumbent, Blockbuster; Process Power, as well as modest spatial distribution Scale Economies relative to other DVD-by-mail wannabes. This Power was not properly recognized by the investment community. My hypothesis proved correct, as Netflix handily beat back other like competitors, while also winning a bruising battle against Blockbuster, with a finale as definitive as any strategist could hope for: on September 23, 2010, Blockbuster declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The dramatic demise of this previously high-flying competitor served as testimony to the potency of the Counter-Positioning I had hypothesized. One might hope that such a victory would have provided a durable sinecure, but that was not in the cards for Netflix, at least not yet. My investment hypothesis carried a two-part caveat. First, I knew DVD rentals were transitory, destined to be supplanted by digital distribution over the Internet

- The second part of my caveat was likewise cautionary: Netflix had no yet-evident sources of Power in this new modality—the technology to stream was accessible to many, and the powerful content owners were implacably committed to wringing every penny from their rights. I suspect Netflix management might have agreed with me on this assumption too

-

The Netflix response to these predicaments? They tested the waters, investing 1–2% of revenue on streaming 79 —not a bet-the-company amount, sure, but hardly trivial. This effort culminated in the launch of the Watch Now feature on January 16, 2007. It was a modest beginning, and the initial offering comprised only about 1000 titles, small compared to their DVD library, which was 100 times larger, but significant still. Customers responded positively, encouraging Netflix to fuel the fire. The company negotiated in turn with each hardware vendor to achieve device ubiquity; they upped their commitment on content, eventually reaching deals with CBS, Disney, Starz and MTV in 2008–2009, and they constantly refined the backend technology needed to make streaming a seamless customer experience

- This was good news, but the second part of my caveat still held—streaming had no apparent sources of Power. At last Netflix had come face-to-face with Professor Porter’s uncomfortable truth: operational excellence is not strategy. Yes, operational excellence is essential and constantly challenging; it rightfully occupies the lion’s share of management’s time. Unfortunately, it does not by itself assure differential margins (a positive m in the Fundamental Equation of Strategy) combined with a steady or growing market share (s in the FES). Competitors can easily mimic the improvements yielded by operational excellence, eventually arbitraging out the value to the business. Netflix suffered many acute operational challenges as it moved into streaming, and gradually addressed them. But even these efforts were insufficient to assure continuing differential returns

- Consider some examples:

- User Interface (UI) development: Netflix rightfully paid a great deal of attention to its UI. The company is a data smart one, and A/B testing of UI alternatives has led to many frequent refinements. Unfortunately, as Blockbuster showed in its mail-order rental competition with Netflix, it is easy to copy a UI

- Recommendation engine: Netflix was a world leader in recommendation engine development, even sponsoring the Netflix Prize, which yielded machine-learning insights still notable in that community. Here one might hypothesize some Scale Economies: as Netflix accumulates more data, the acuity of their recommendations increases. True, but not linear: these advantages paid only diminishing returns, meaning a smaller competitor of an attainable scale could realize most of the same benefit

- IT infrastructure: Video consumes a prodigious amount of bandwidth and storage: by 2011, for example, Netflix had become by far the largest user of peak bandwidth on the Internet. They took the view—perhaps unexpected for a technology company—that this was not their core “competence and made the decision (correctly, in my view) to outsource their information technology (“IT”), eventually ending up as a large customer of Amazon Web Services. This relieved many of their IT expansion headaches and allowed them to focus on what they do best

- Each of these areas required relentless and expert focus, and yet solving this multiplicity of problems was not enough. All of the advances could be more or less mimicked by others in the longer term. The potential for Power remained elusive

- Consider some examples:

-

Netflix realized that content lay at the heart of the problem. After all, great content ultimately represents any streamer’s core value proposition, and for Netflix, it accounted for the bulk of their cost structure. Unfortunately, content holders could “variable cost price” the programming they licensed, charging Netflix according to usage. This put other licensors on an even footing with Netflix, regardless of scale, thus eliminating any chance of Power

- Ted Sarandos, the strategically acute Netflix content head, took the first step in addressing this challenge by pursuing exclusives. At first blush, exclusives seemed a poor choice for Netflix: their higher price meant less content for subscribers. Nevertheless, on August 10, 2010, Netflix and Epix agreed to an exclusive agreement:

- Adding EPIX to our growing library of streaming content, as the exclusive Internet-only distributor of this great content, marks the continued emergence of Netflix as a leader in entertainment delivered over the Web,” said Ted Sarandos. This changed the game. The price of an exclusive was fixed, which meant some content no longer carried a variable cost. All of a sudden Netflix’s substantial scale advantage over other streamers made a difference. But the owners of potential exclusive properties could take note of Netflix’s success. Eventually they would resort to bargaining hard for an outsized share of those returns, even using other streaming competitors as stalking horses. In fact, Epix did exactly this, ending its deal with Netflix and signing up instead with Amazon on Sept 4, 2012

- So again, with Sarandos’ approbation, Netflix took the next logical step—originals. Here they“took a page out of HBO’s playbook—that network’s transition to originals had secured their position as a premium cable juggernaut years before. First for Netflix was the modest Lilyhammer, but on March 16, 2011, Netflix dropped a bomb. Deadline Hollywood splashed: Netflix To Enter Original Programming With Mega Deal For David Fincher-Kevin Spacey Series ‘House Of Cards’. Netflix plunked down $100 million, beating out HBO, CBS and Showtime to lock up twenty-six episodes, two full seasons of the political thriller. It was a big bet, and despite modest assurance from their user stats, a large risk.They were rewarded with increased subscriptions and numerous awards, including nine Primetime Emmy Nominations, a victory on the Benefit side, but also the beachhead for a victory on the Barrier side. Originals unequivocally rendered content a fixed cost, guaranteeing powerful Scale Economies, and they also permanently altered Netflix’s bargaining position with content owners. As Reed Hastings put it:“…If the television networks stop selling shows… the company has a game plan. We just do more originals….” Fast forward to 2015. Originals have now become the centerpiece of Netflix’s strategy

-

The value created by this robust strategy has been stunning, a nearly 100x gain in share price, culminating in a market cap of about $50B.” “With Netflix, we saw that creating the streaming business and then segueing to originals propelled their “route to continuing Power in significant markets.”

- With an eye toward deducing a more general understanding, let’s take a step back, reexamine all seven types of Power and ask the Dynamics question “What must you do to get there?”

- Scale Economies: With this first Power type, you must simultaneously pursue a business model that promises Scale Economies (industry economics), while at the same time offering up a product differentially attractive enough to pull in customers and gain relative share (competitive position)

- Network Economies: Here the needs are similar to Scale Economies, except that installed base, rather than sales share, is the goal

- Cornered Resource: You must secure the rights to a valuable resource on attractive terms. This often comes from having developed that resource in the first place and then gaining ownership of it, the most common avenue being a patent award for research developments

- Branding: Over an extensive period of time, you make the consistent creative choices which foster in the customer’s mind an affinity that goes beyond the product’s objective attributes

- Counter-Positioning: You pioneer a new, superior business model that promises collateral damage for incumbents if mimicked.

- Switching Costs: With Switching Costs, you must first attain a customer base, meaning the same new-product requirements demanded of Scale and Network Economies factor in here as well

- Process Power: You evolve a new complex process which renders itself inimitable within a reasonable period and yet offers significant advantages over a longer period of time

- The Topology of Invention and Power

- So what are the elements of this dance of Power and invention? The script usually plays like this: Flux in external conditions creates new threats and opportunities. In the case of Netflix, it was both: the eventual decline of their DVD-by-mail business was the threat, and streaming the opportunity

- The nature of flux demands that it unfolds in fits and starts, so any company wishing to capitalize on these new conditions must invent—again, by crafting, not design. For a single company, these tectonic shifts do not occur frequently, but you can be certain they are coming. The relentless forward march of technology assures this

- Amidst this cacophony, you must find a route to Power. It wasn’t a fine-tuning of their DVD-by-mail business which increased Netflix’s market cap by a factor of 100; it was streaming, with its insurmountable Scale Economies

- Now let’s apply this framework to Netflix streaming:

- Resources: You must start with the abilities you can bring to bear. Using the academic convention, I will call these “resources.” They might be as personal and idiosyncratic as Steve Jobs’ aesthetic sensibilities, or as corporate as Google’s vast stores of organized data. For Netflix, their original DVD-by-mail business endowed them with numerous resources relevant to streaming, including such directly transferable skills as their recommendation engine, their UI, their customer data and their relationships with content owners. Equally important was the platform of their existing business, which allowed them to easily offer streaming as a complement to DVD-by-mail, rather than a standalone service. This was far more important than you might think, as it silenced potential complaints about the initial small streaming catalogue that could have driven fatally negative word-of-mouth. Conversely, though, there were also many abilities Netflix had to develop, and as they moved aggressively into originals, this set of required competencies expanded considerably

- External conditions: These resources then intersect an opportunity set driven by evolving external conditions: technological, competitive, legal and so on. For Netflix, an advancing technology frontier opened up the potential for streaming: Moore’s Law in semiconductors, plus similar exponential advances in optical communications and storage. The embodiments of these trends were high-speed Internet connections, acceptably costed digital storage and a broad dispersion of devices with adequate performance (displays, storage, graphics processing and connectivity). If Netflix had bet the company on streaming any earlier, they would have been dead in the water—external conditions were not yet ripe

- Invention: For Netflix, the inventions were their new product directions: streaming and originals and all the associated complements. Crafted, not designed

- Power: The final step was the thrust into exclusives and originals. By bringing to rein the cost of content, Netflix forged powerful Scale Economies and hence Power. Most inventions don’t assure Power. As I have discussed, operational excellence—really a constant process of re-invention—does not result in Power

- So if you want to develop Power, your first step is invention: breakthrough products, engaging brands, innovative business models. The first step, yes, but it can’t be the last step. Had Netflix invented the streaming product without introducing originals, they would have been left with an easily imitated commodity business. There would have been no Power and little value in the business

-

Invention: the One-Two Value Punch: So far, so good. By looking through the lens of the 7 Powers, we have come to a vital insight: Power arrives only on the heels of invention. If you want your business to create value, then action and creativity must come foremost

-

But success requires more than Power alone; it needs scale. Recall the Fundamental Equation of Strategy: Value = [Market Size] * [Power]

-

In Statics, rightfully, we focused solely on Power and took market size as a given. Not so with Dynamics. Recall that Netflix’s invention (streaming) not only created an opportunity for Power but created the streaming market as well. Both factors must be present to bring about value increases of 100x. Invention has a powerful one-two value punch: it both opens the door for Power and also propels market size

-

Invention drives a favorable change in system economics—you get more for less. The resulting gain in the end will be split somehow between your company and other segments of the value chain. The 7 Powers is all about making sure that you get some of the increase. But it is the gain customers experience that will shape the market size. In the Netflix streaming case, if customers hadn’t responded favorably to this new delivery mode, then all opportunities for Power would have come to naught. The remainder of this chapter will explore this customer value side. I will use the phrase “compelling value” 91 to characterize products that are sufficiently superior in the eyes of the customer to fuel rapid adoption; they evoke a “gotta have” response. It is this impetus that drives the left-hand side of the FES, market size

- Compelling value requires that you mobilize your capabilities to offer up a product that fulfills a significant customer need currently unmet by competitive offerings. This need drives customer adoption

Capabilities-Led Compelling Value: Adobe Acrobat Case Study

-

There are three distinct paths to creating compelling value. Each has different tactical needs, so it is instructive to think of them separately. First is Capabilities-led compelling value: when a company tries to translate some capability into a product with compelling value

-

Consider Adobe’s creation of Acrobat. Here the key capability brought to bear was Adobe’s existing fluency at the intersection of software and graphics. John Warnock, Adobe’s co-founder, wanted to utilize this expertise to create a software that enabled the sharing of documents transparently across diverse computer platforms while exactly maintaining visual integrity

-